|

To our page on

Art Pottery

| |

Important Message

This Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

Will be at the bottom of most web pages!

Please read it before using this website.

Thank You

|

|

Categories within Art Pottery:

|

Click a photo to link to a page on our website. Links are found on nearly all Web pages.

Links allow users to click their way from page to page. You will find thousands of links on this website.

|

|

| Rookwood Pottery |

|

|

|

| Roseville Pottery |

|

|

|

| McCoy Pottery |

|

|

|

| Red Wing Pottery |

|

|

|

| Van Briggle Pottery |

|

|

|

| Shawnee Pottery |

|

|

|

| Roseville Pottery |

|

|

Identification of Roseville USA Pottery Just about all Roseville pottery was marked in some way, but over the years some of the less permanent methods have been washed or peeled off, such as early red crayon marks on the underside of pieces or triangular foil and paper labels. Other more permanent common marking methods were raised or impressed marks in the clay with the word "Roseville USA" also conjoined "RV" ink stamps as shown were used on early pieces.

|

There are also a host of other marks used over the years. Your best source to find these marks are any of the many books available that chronicle the work of the Roseville USA Pottery Company. Such as the two listed below. Often, you will also find the shape number and the height of the piece impressed in the bottom as seen in the photo above left or notated with the previously mentioned red crayon. The impressed mark above is a Roseville Pine Cone 18" ewer, shape number 416.

|

|

Quality Art Pottery

We sell Art Pottery, specializing in Hull, McCoy, Nippon, Red Wing, Rookwood, Roseville, Shawnee, Van Briggle and Weller Pottery. Our shop is in West St Paul, Minnesota. Most of the items which we carry in our Mall are collectible grade and are free from chips, flakes, hairline cracks, and heavy crazing. Any piece which is not collectible grade will have an AS/IS on the item. And will be in the item description. Almost all Art Pottery exhibits some degree of crazing but we only offer pottery with light, mild, or no crazing. All item descriptions include photos which will provide a full view of each piece.

|

Important Message

Items pictured on this web site are mainly used for educational value.

They may or may not be available in our shop.

Please check before coming.

|

We also routinely offer...

|

Studio/ Handcrafted Pottery

American Bisque

Art pottery vases

Colorado Pottery

Coors Pottery

Franciscan/ Gladding-McBean

Central/South American Pottery

Price Guides & Publications

|

![]()

|

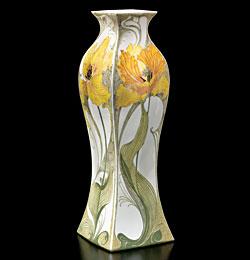

ABOVE, LEFT: Fig. 1: Hans Nosek for Ceramic Art Company, Trenton, N. J. Two-handled vase with scenic decoration, 1905. Porcelain, enamel, gold. H. 17, W. 12, Diam. 8-1/2 in. Marked: Printed green mark, CAC in a wreath above LENOX. Gift of Brown-Forman, Incorporated, 2006 (2006.45.1). ABOVE, RIGHT: Fig. 2: Maria Longworth Nichols for Rookwood Pottery, Cincinnati, Ohio. “Oriental” vase, 1883. Earthenware with underglaze slip decoration. H. 20-1/2, Diam. 10-1/2 in. Marked: impressed on bottom, kiln-shaped stamp, G (ginger clay), ROOKWOOD / 1883. Purchase 1985 Mathilde Oestrich Bequest Fund and Eva Walter Kahn Bequest Fund (85.281).

|

The Newark Museum, founded in 1909, began collecting art pottery from the start. From its first art pottery exhibition in 1910 until the death of its founding director, John Cotton Dana, on the eve of the Great Depression, the museum was one of the nation’s pioneers in the exhibition of ceramics as art. For its centennial, the museum has mounted an exhibition that explores this idea, 100 Masterpieces of Art Pottery, 1880–1930.

Artistic ceramics is not a new concept. However, in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, there was increasing reaction against industrial, “soulless” factory production coupled with a growing awareness in the

West of revered ceramic traditions from Asia. All of this came together, for the United States at least, at the national Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. It was in the aftermath of the Centennial that Americans began to see the potential for transforming domestic ceramics from merely decorative objects into art objects—in their shape, glaze, and surface treatment.

The Arts and Crafts aesthetic that still tends to define art pottery today did not dominate the decorative arts in America in the early part of the twentieth century. The inclusion of Lenox china (Fig. 1) in the Newark Museum’s 1910 Modern American Pottery exhibition, alongside Grueby and Newcomb, reminds us that porcelain was also seen as art pottery. Walter Scott Lenox ran his Ceramic Art Company in the same way Rookwood and Grueby were run, with different segments of the production process assigned to specific people or groups of people, from glaze chemists and potters to kiln-loaders to decorators. His aesthetic goals were similar (to make art from clay), and his desire to balance art and commerce was the same. Like them, he was influenced by contemporary taste, and he was deeply involved in current ceramic technology.

|

|

| Fig. 3: Worcester Royal Porcelain Works, Worcester, England. Two-handled vase with design of pansies, 1890–1891. Porcelain with enamel decoration. H. 11-3/4, Diam. 7 in. Marked: printed Royal Worcester crowned mark with printed registration mark. Gift of J. Ackerman Coles, 1926 (26.1117). |

|

|

|

| Fig. 4: Pierre-Adrien Dalpayrat, Bourg-la-Reine, France. Baluster form vase, ca. 1895. Stoneware with mottled red glaze. H. 12-1/2, Diam. 6 in. Marked: impressed “pomegranate” mark, 2033 and an impressed signature, Dalpayrat. Purchase 2007 Membership Endowment Fund (2007.34.1). |

|

|

|

| Fig. 5: George E. Ohr (Biloxi Art Pottery), Biloxi, Miss. Vase with green and red glazes, 1894–1898. Earthenware. H. 8, Diam. 5-1/2 in. Marked: impressed GEO. E. OHR, / Biloxi, Miss. Purchase 1982 Sophronia Anderson Bequest Fund (82.27). |

|

|

|

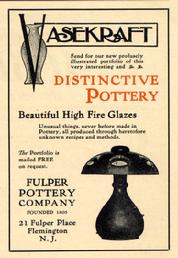

| Fig. 6: Fulper Pottery Company, Flemington, N.J. Amphora vase with “peach bloom” glaze, 1914. Molded stoneware. H. 8-1/2, Diam., 3-1/2 in. Marked: oval ink stamp FULPER obscured by paper Vasekraft label as noted above; inked inscription: Amphora / Vase / Peach / Bloom / $40. Purchase 1915 (15.6). |

|

|

The art pottery business model involved divisions of labor, hierarchies of art and craft, and (of course) the balancing of art with profit. At the same time, however, the work of such pioneer studio potters as Adelaide Robineau, Frederick Walrath, and William Joseph Walley (in the United States) and Adrian Dalpayrat, Edmond Lachenal and Auguste Delaherche (in France) arose from the idea of making art first, profit second. Moreover, in Europe artists often worked in studio-like settings within factories (Christian Neureuther and Michael Powolny in Germany, Arthur Percy in Sweden). They produced ceramic objects that do not fit today’s idea of art pottery, but which were certainly collected as such in the 1910s and 1920s.

At the 1876 Centennial, Japanese and Chinese ceramics were seen by millions of visitors, as was the new “barbotine” decoration (painting under the glaze with liquid clay), perfected by Ernest Chaplet at the Haviland factory in Limoges, France.1 Two core concepts grew out of this moment relative to art pottery: the vessel as a canvas to be painted and the vessel as a sculptural object. Each would develop in its own way as the Gilded Age moved toward the twentieth century.

China Painters & the Art Pot

Art pottery was the offspring—or perhaps the sibling—of the china painting vogue that burgeoned in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Maria Longworth Nichols (1849–1932), founder of the Rookwood Pottery, had started china painting in 1873, joining affluent women all over the country in this newly fashionable hobby. Dazzled by the Centennial Exhibition, and financed by her father, Nichols established her pottery in Cincinnati in 1880. It was America’s first official art pottery.2 Rookwood’s goal was to make pottery that was art, and to make that art commercially viable. The heavier technical work such as mixing clay, potting, and firing, was done by men, while the painting and decoration was done by both men and women, who were allowed to sign their pots. The early pots from Rookwood were strongly reflective of the Aesthetic movement and its fascination with Near- and Far-Eastern design (Fig. 2). The Rookwood technique of underglaze painting was developed from French “barbotine” or “Limoges” decoration.

Enameling on either porcelain or fine white earthenware was already a well-established tradition by 1876. European and Asia ceramic factories—from Satsuma, Japan, to Worcester, England—had specialized in exquisitely rendered floral decoration, landscapes, and mythological scenes since the development of low-fire enamels in the early eighteenth century. Enamellers generally worked on blanks designed and made by others; as was also true in art potteries, where ceramic decorators were kept apart from the potters and technicians.

European art porcelain in the late nineteenth century mingled Japanism with other aesthetic influences. Royal Worcester’s ivory-bodied enameled wares (Fig. 3) were the standard against which American efforts at porcelain production were judged. The elaborate enameling and raised goldwork on Worcester porcelain paralleled similarly complex decoration on Japanese pottery and porcelain. English-born Edward Lycett (1833–1892) used his skills as a china painter to produce Worcester type ceramics at the Faience Manufacturing Company in Brooklyn in the 1880s.3 Considered the father of china painting in America, Lycett’s work demonstrated a close knowledge of both Japanese and English art pottery. The late twentieth-century appreciation of the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts styles marginalized the romantic decoration and gilded details of china-painted porcelain; but one shouldn’t forget that, to Walter Scott Lenox, who hired skilled European china-painters to decorate his vases, his porcelains were as much art as were Rookwood’s painted pots.

|

The Minimalist Art Pot

The counterpoint to the exotic patterns and colors of Japanism in the 1870s were the monochromatic Chinese porcelains that depended entirely on simple forms and beautiful glazes. The Chinese displays at the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 were enormous, but they offered less novelty to American eyes, and caused a less obvious public sensation. The founding collection of the Newark Museum in 1909 was overwhelmingly Japanese, but it included a large number of Chinese monochrome porcelains. The importance of these minimalist form-and-glaze art pots has been underestimated by most recent scholarship. However, there is no question that from the 1890s to the 1920s, these minimalist art pots epitomized the ceramic artist’s attempt to capture the essence of pottery as art through the rediscovery of the primal beauty of glazed clay.

Hugh Robertson and Adrien Dalpayrat exemplify the minimalist art potter at work on both sides of the Atlantic. In Massachusetts, Hugh Robertson (1845–1908) produced a line of austere Chinese-form vases with deceptively simple, richly textured glazes, in a wide range of colors. Never profitable, Robertson’s art pottery was subsidized by the popular blue and white crackled dinnerware lines developed in the 1890s that bore the Dedham name. His “volcanic” line was closer to studio pottery than art pottery, lacking the technical predictability that was a necessity for an art pottery that relied on consistency from the kiln.4 In France, Adrien Dalpayrat (1844–1910), who was born and trained as an artist and china painter in Limoges, focused on a high-fired (grand feu) vitreous stoneware (grès) body and simple forms covered with superb glazes (Fig. 4) that gained him a bronze medal in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and a gold medal in the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900.5

Even George Ohr (1857–1918) from Mississippi was clearly knowledgeable about Chinese forms and glazes. Ohr was the best thrower in the world in his day, and was the first American potter to push the art pottery envelope, manipulating his thin earthenware bodies in ways most Americans wouldn’t imagine until decades later (Fig. 5). He was also one of the first studio potters in America, working largely alone, and overseeing every aspect of his work directly.

|

|

| Fig. 7: Carl Schmidt for the Rookwood Pottery, Cincinnati, Ohio. Vase with decoration of irises and “black iris” glaze, 1909. Thrown white earthenware with underglaze slip decoration. H. 13-3/4, Diam. 5-1/2 in. Marked: impressed RP cipher above IX for 1909, impressed form mark 907C, and W (white clay) and CS artist’s cipher. Red and white paper Rookwood label with inked price of $100. Purchase 1914 (14.446). |

|

|

Both the commercially successful “Vasekraft” line of New Jersey’s Fulper Pottery (Fig. 6), and the hand-made, one-off porcelain gems of studio potter Adelaide Robineau (1865–1929) reflected a reverence for Chinese monochrome minimalism. Fulper, who showed at the Newark Museum in 1915, and Robineau, who sold three little pots to the museum in 1914 (the first acquisition by a museum of her work), used simple Chinese forms with carefully studied glazes achieved through much experimentation. Both Fulper and Robineau carried on the tradition of potters from the 1890s such as Robertson and Dalpayrat, but their output in the 1910s and 1920s reflects an ongoing interest in minimalist art pottery that was seen as modern in the 1920s.

The Painterly Art Pot

The painted vase was the ideal ceramic art object, because, while functional, it did not have to serve a purpose other than contemplation. Stylistically, the vessel followed the aesthetic trends of the moment. In instances where the artist who decorated a pot and the potter who made it were not the same person (as was the case in almost every quasi-commercial art pottery), the decorative artist normally received the recognition, because his or her talents were seen as higher on the artistic scale than the manual skills of the potter. Rookwood exploited the reputations of its best artists (Fig. 7), as did European potteries such as Rozenburg in the Netherlands (Fig. 8) and Wachtersbach in Germany.

On the other hand, art potteries limited the artistic freedom of their artists, requiring them to follow designs created by others and to stick to the general aesthetic guidelines that created the specific pottery’s “look.” The artists at Newcomb College Pottery in New Orleans were allowed some room to grow artistically––more, say, than their peers at Arthur Baggs’ Marblehead Pottery (Fig. 9)––but even they were circumscribed by the pottery’s overarching aesthetic goals and the need to sell. The eggshell porcelains produced at the Rozenburg factory in The Hague had to conform to the ethereal Art Nouveau style established as their main feature, and the pared-down stylizing adopted by Christian Neureuther’s studio at the Wächtersbach stoneware factory had to be commercially viable to survive.

|

|

| Fig. 8: Samuel Schellink for Rozenburg Pottery, The Hague, Netherlands. Square baluster vase with decoration of tulips, 1909. Molded porcelain. H. 10-1/2, W. 4, D. 4 in. Marked: Printed in black on bottom: crown, above the word “Rozenburg” (curved up) above a stork, above “den Haag” (curved down). To the left a printed torch (date code for 1909); to the right a painted box with a cross in it and 290, (work order number), above a squared S with a vertical line through it and a period (Samuel Schellink’s cipher). Purchase 2007 Membership Endowment Fund (2007.34.3). |

|

|

|

| Fig. 9: Sarah Tutt and John Swallow for Marblehead Pottery, Marblehead, Mass. Vase with stylized flowers, ca. 1910. Thrown earthenware with applied slips. H. 7, Diam. 4 in. Marked: incised insignia of a frontal view of a ship in full sail, flanked by initial M and P; incised HT; oval paper label with MARBLEHEAD POTTERY printed in black. Purchase 1911 (11.489). |

|

|

|

| Fig. 10: Clément Massier, Vallauris, Golfe Juan, France. Jardinière with figure of a woman, 1900. Earthenware with iridescent glaze. H. 10, Diam. 15 in. Marked: incised CM / 1900 / 2. Purchase 1999 Friends of the Decorative Arts (99.17). |

|

|

|

| Fig. 11: Ruth Erickson for the Grueby Pottery Company, Boston, Mass. Vase with scrolled handles, 1900–1909. Earthenware with applied decoration. H. 10-1/2, Diam. 5-7/8 in. Marked: impressed circular mark GRUEBY / POTTERY CO / BOSTON USA, with incised RE cipher. Purchase 1911 (11.487). |

|

| The Sculptural Art Pot

If the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia was a seminal event in the transformation of decorated ceramics into art; then it was equally the wellspring—in America at least—for the sculptural possibilities of ceramics. Professor Isaac Broome, working for Trenton’s Ott and Brewer, brought the artistic spotlight to ceramic sculpture in 1876.6 Broome, however, only made a few actual pots, preferring busts and figures. Just as was true with painterly pots, sculptural art pottery evolved as artistic taste and aesthetic ideology changed over time.

Among the many European art potters who worked in sculptural ceramics, Clément Massier (1845–1917) established his first ceramic studio in 1872 in Vallauris in the Golfe Juan area of the French Riviera, and became famous for his metallic luster glazes (Fig. 10). Massier moved from the Japanism of the 1870s to the Art Nouveau of the 1890s, producing sculptural vessels that shimmered with surfaces unlike any other in the world. One student of Massier’s, Jacques Sicard, would take the secret of these glazes to America and build his own reputation with them in the early twentieth century.

The plainer, low-key translation of the sculptural qualities of the Art Nouveau in America is exemplified by the stylized foliage, simple outline, and silky matte glaze of Grueby pottery. A vase purchased by the museum in 1911 for half of its retail cost of $50 (Fig. 11), was modeled by Ruth Erickson (ca. 1899–1910), but, as was usually true in art potteries, her role in the artistic development of the vase was limited to the physical application of someone else’s designs. Inspired by French potters seen at international exhibitions, Grueby achieved huge success, winning a gold medal at the Paris exposition of 1900 and the Saint Louis exposition in 1904. Ironically, Grueby’s participation in the Newark Museum’s 1910 exhibition was the last public display of Grueby pottery in William Grueby’s (1867–1925) lifetime. For all his artistic success, the financial aspect of running an art pottery had eluded him.

|

Former Rookwood decorator Artus Van Briggle was already long dead by the time his work was included in the Newark Museum exhibition in 1910 (Fig. 12). Van Briggle had adapted French art pottery’s low-relief sculptural effects and focus on superb glazes to the American market, slip-casting his designs and experimenting with innovative glazes.7 His enterprising widow continued to develop Van Briggle designs for decades after her husband’s death. With converse irony, Van Briggle’s commercial success has resulted in its artistic devaluation in the eyes of collectors and curators.

100 Masterpieces of Art Pottery, 1880–1930 will run until January 10, 2010, at the Newark Museum. Art pottery, in all its manifestations between 1880 and 1930, is explored in the accompanying centennial catalogue.

Ulysses Grant Dietz is curator of decorative arts at The Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey.

1. Ulysses G. Dietz, “Art Pottery 1880–1920,” in Barbara Perry, ed., American Ceramics, The Collection of Everson Museum of Art (Syracuse and New York: Everson Museum of Art and Rizzoli, 1989), 61.

2. See Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Aesthetic Forms in Ceramics and Glass,” in In Pursuit of Beauty, Americans and the Aesthetic Movement (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Rizzoli, 1986), 228.

3. He taught in Saint Louis and in Cincinnati, where he fired some of Maria Longworth Nichols’ own amateur china painted ceramics. See Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, “Aesthetic Forms in Ceramics and Glass,” in In Pursuit of Beauty, Americans and the Aesthetic Movement (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Rizzoli, 1986), 426.

4. See Paul Evans, “Context and Theory, Binns as the Father of American Studio Ceramics,” in Margaret Carney, ed., Charles Fergus Binns The Father of American Studio Ceramics (New York City and Alfred, NY, Hudson Hills Press and New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, 1998), 103. Also Paul Evans, Art Pottery of the United States (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1974, reissued by Feingold & Lewis Publishing Group, 1987), 83.

|

|

| Fig. 12: Artus Van Briggle for the Van Briggle Pottery, Colorado Springs, Col. Vase with apple green glaze and floral relief, 1903. White earthenware. H. 11-1/2, Diam. 4 in. Marked: Incised AA cipher in a square / VAN BRIGGLE / 1903 / III, and impressed 233 model number. Purchase 1929 (29.1003). |

|

|

5. See Henry-Pierre Fourest, L’Art de la Poterie en France de Rodin a Dufy (Sèvres, France: Musée National de Céramique, 1971), 25. Also see www.ceramique1900.com/dalpayrat.html.

6. For a detailed history of early porcelain sculpture in America, see Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, American Porcelain, 1770–1920 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), 166–179.

7. See Barbara M. Arnest, ed., Van Briggle Pottery, The Early Years (Colorado Springs: Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, 1975), 65–66.

|

|

|

| _Fulper Pottery Company's_ Brief History |

|

| |

Customer Satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. We accept returns on all items. (Please see our " Returns Policy" for details). We have been selling Art Pottery in our Mall for over 16 years including eBay.

|

To all Visitors

This site has been developed not just to sell Antiques and Collectibles (of course it does some of that) rather it is to provide information about Antiques, Collectibles, artwork, art pottery, furniture types, furniture styles, jewelry, and militaria from the Revolutionary War to the Vietnam War. This site is all about information and history that is not readily available elsewhere on the Internet. We think West St Paul Antiques is one of the best Antique Malls in the State of Minnesota and we have been working hard to create that excellence for the last 25 years. We have expertise on Antiques & Collectibles and as we read and study about history and antiques we also strive to be historians. We will share that expertise with you and all the visitors to our site. Stop by and visit our Antique Mall in West St Paul, Minnesota.

Or, you are all welcome to visit us on the web.

Oh, by the way, also check out all our Antiques, Collectibles, artwork, art pottery, clocks, mall specials, furniture types and styles, jewelry and militaria items for sale in our Antique Mall. Check it out by going to Antique Mall Tour. This site will be totally commercial free with no fees to pay. I'll be working on this site over time so bear with me. It should be finished by the end of 2048 with over 10,000 pages at that time and 500 pages by the end of next year.

Click here to go to our web Site Map and Categories.

|

This website contains, in various sections, portions of copyrighted material not specifically authorized by the copyright owner. This material is used for educational purposes only and presented to provide understanding or give information for issues concerning the public as a whole. In accordance with U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. More Information

Information presented based on medical, news, government, and/or other web based articles or documents does not represent any medical recommendation or legal advice from myself or West Saint Paul Antiques. For specific information and advice on any condition or issue, you must consult a professional health care provider or legal advisor for direction.

I and West Saint Paul Antiques can not be responsible for information others may post on an external website linked here ~ or for websites which link to West Saint Paul Antiques. I would ask, however, that should you see something which you question or which seems incorrect or inappropriate, that you notify me immediately at floyd@weststpaulantiques.com Also, I would very much appreciate being notified if you find links which do not work or other problems with the website itself. Thank You!

Please know that there is no copyright infringement intended with any part of this website ~ should you find something that belongs to you and proper credit has not been given (or if you simply wish for me to remove it),

just let me know and I will do so right away.

|

Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

By using this website, West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, you are agreeing to use the site according to and in agreement with the above and following terms of use without limitation or qualification. If you do not agree, then you must refain from using the site.

The 'Terms of Use' govern your access to and use of this website and facebook pages associated with it. If you do not agree to all of the Terms of Use, do not access or use the website, or the facebook sites. By accessing or using any of them, you and any entity you are authorized to represent signify your agreement to be bound by the Terms of Use.

Said Terms of Use may be revised and/or updated at any time by posting of the changes on this page of the website. Your continued usage of the website, or the facebook site(s) after any changes to the Terms of Use will mean that you have accepted the changes. Also, any these sites themselves may be changed, supplemented, deleted, and/or updated at my sole discretion without notice; this establishes intellectual property rights by owner (myself).

It saddens me to include a Terms of Use for West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, but we all realize it is something that is necessary and must be done these days. By using the website, or facebook for West Saint Paul Antiques, you represent that you are of legal age and that you agree to be bound by the Terms of Use and any subsequent modifications. Your use of the West Saint Paul Antiques sites signify your electronic acceptance of the Terms of Use and constitute your signature to same as if you had actually signed an agreement embodying the terms.

|

|

|

| Me with your feedback on how I can Improve this website. |

|

| |

|