Important Message

This Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

Will be at the bottom of most web pages!

Please read it before using this website.

Thank You

|

|

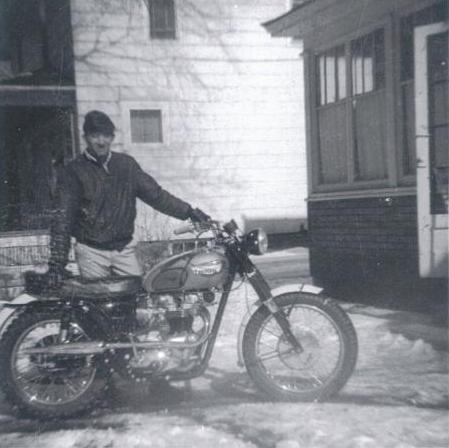

| David Hoffman 1965 - 1708 Emerson Ave. North Minneapolis |

|

|

|

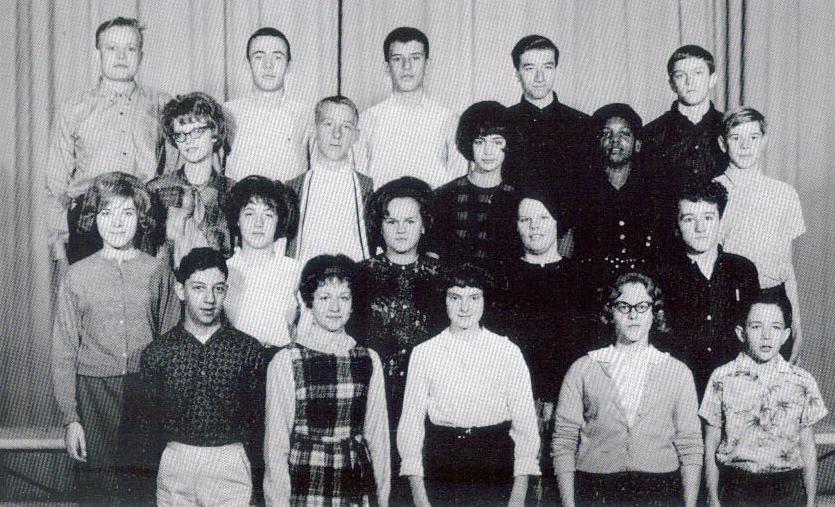

| David Hoffman 1964 |

|

|

|

| David Hoffman 1963 |

|

|

|

| David Hoffman 1964 |

|

|

|

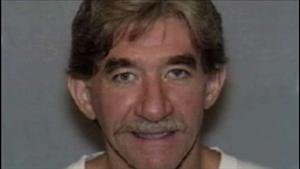

| File photo of David Hoffman 1990-2000 |

|

|

|

| David Hoffman 1963 |

|

|

On this Date in Minnesota History

August 10, 1980

|

|

David Francis Hoffman choked his wife, Carol Stebbins Hoffman, to death in their bedroom while their 9-month-old daughter was in the room. “His mother, who reportedly knew of her son's plans, kept [their 3-year-old daughter] distracted while he dismembered his wife's body [in the bathroom].

Hoffman first tried to dispose of the body in a garbage disposal but ultimately ended up burning some of the remains in the back yard and then tossing the rest into nearby Weaver Lake.”

In the days immediately following the killing, “a mournful David Hoffman was seen on the [TV] evening news leading efforts to locate his wife, who he told police had inexplicably run off.

The case gained so much notoriety that the subsequent trial was moved from Minneapolis to Rochester because of negative pre-trial publicity.

[Hoffman] claimed that he strangled his wife for a variety of reasons, including that she was going to divorce him and he feared he might not see his daughters again.

[However] Hoffman, who pleaded guilty by reason of insanity, also said he killed Carol Hoffman because he believed she was possessed by the devil.

In testimony, Hoffman and friends testified that he told them, and his mother, that he wanted to kill his wife and might have been planning the killing for months or years.

Eventually a jury convicted Hoffman of first-degree murder. He received a life sentence. His mother was convicted of the same crime, but that conviction was overturned about a year later by the Minnesota Supreme Court.”

|

|

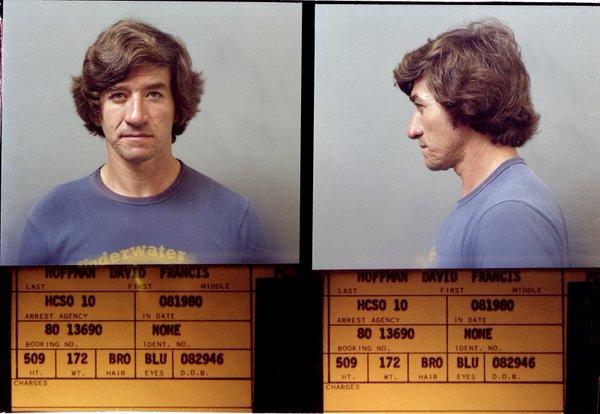

| David Hoffman 1980 |

|

|

Wife-killer Hoffman denied parole

It was his third try for parole since he was convicted in 1981 of killing and dismembering his wife.

He can't make another bid for six years.

|

JUNE 21, 2010 — 9:31PM

By HERÓN MÁRQUEZ ESTRADA Star Tribune

|

|

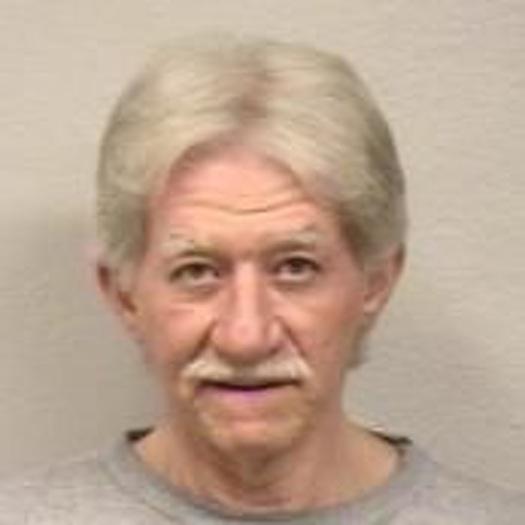

| David Hoffman 2010 |

|

|

Convicted murderer David Hoffman was denied parole Monday and must serve at least six more years in prison for strangling and dismembering his wife almost 30 years ago in western Hennepin County.

Hoffman, now 63, was convicted in 1981 of killing his wife, Carol Stebbins Hoffman, in their home in Corcoran. He tried to dispose of her body in a garbage disposal and later threw the remains in nearby Weaver Lake.

On Monday, the state Department of Corrections, in denying his parole request, ruled Hoffman must serve at least six more years before he is eligible to reapply for parole.

Relatives of Carol Hoffman have been working for the past 30 years to keep Hoffman incarcerated.

"It was a relief," said Phyllis Stebbins, Carol's mother, who was among the Stebbins family members attending Monday's review. She called it "a little closure on the nightmare."

The Stebbins family says Hoffman, who is housed at Moose Lake prison, shows no remorse about the killing.

|

|

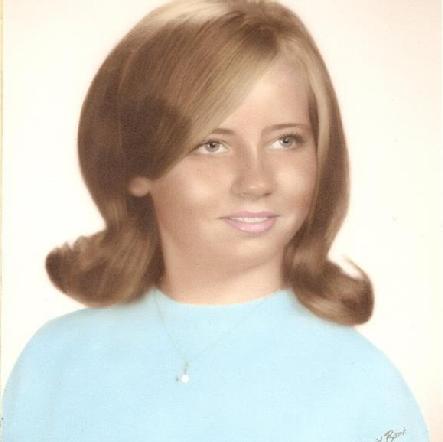

| Carol Hoffman's high school graduation photo from 1971 |

|

|

Hoffman's sister, Delores Olean of Columbia Heights, said, "Another six years doesn't surprise me; another 10 years wouldn't surprise me. It was a vicious, vicious crime that never should have happened. A couple years ago I thought maybe there was a chance at 30 years that he would get out."

Monday's review, which was closed to the public, marked the third time Hoffman has tried for release. He was denied in 1994, the first time he was eligible, and again in 2000.

Both times the state corrections commissioner cited Hoffman's lack of remorse as among the reasons he was not released, corrections records show.

Corrections Commissioner Joan Fabian said in her decision Monday that Hoffman had not met all of the conditions set during his last review in 2000. Fabian did not elaborate.

|

Carol Hoffman had two daughters who were ages 3 years and 9 months when she was killed in August 1980. The murder was one of the most notorious in Hennepin County history at the time, according to police.

David Hoffman admitted to the killing but pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. He was convicted of first-degree murder.

Also convicted was his mother, Helen Ulvinen, who reportedly knew about the plan to kill her daughter-in-law. Her conviction was overturned in 1981 by the Minnesota Supreme Court.

Katherine Stebbins, Carol's sister, said Monday's decision bought the family some time.

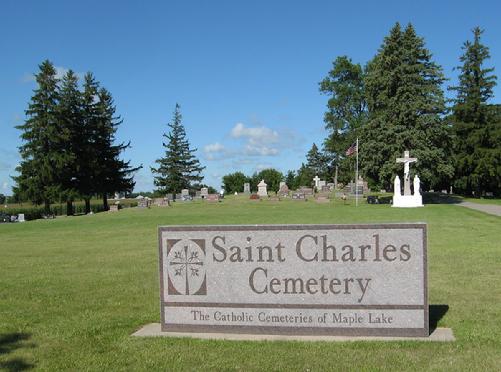

"We know that in another six years we're going to have to fight this all over again," she said from the Anoka County cemetery where her sister is buried. "But as long as he's in [prison] he can't hurt anybody.

Hoffman's sister said that her brother has shown remorse over the years and should be released.

"I have been sitting across from him in prison and he broke down, it was so sad to see,"

Olean said. "He's been in there for 30 years. It's a total lie that there has been no remorse."

|

David Hoffman denied parole in murder and dismembering of wife.

TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 2010 AT 8 A.M.

BY HART VAN DENBURG

|

|

| David Hoffman 2010 |

|

|

By the time David Hoffman was done with his late wife, Carol, he'd choked her to death, cut her up, tried to feed the pieces to the garbage disposal, and then dumped them in Weaver Lake.

That was in 1980.

Yesterday, the 63-year-old Corcoran man was denied parole on his 1981 conviction for the third time, with a new parole review scheduled six years from now. Hoffman has apparently failed to live up to parole conditions, and has not shown remorse for his actions.

Phyllis Stebbins, Carol Hoffman's mother, told WCCO she feared Hoffman would kill again if he were back on the streets.

Here's the Department of Corrections statement:

|

|

|

David F. Hoffman, serving a life sentence for the 1980 death of his wife Carol Hoffman, was denied parole today by Corrections Commissioner Joan Fabian. His case was continued for review in six years. In making her decision, Commissioner Fabian said that Hoffman had not met all directives given to him at his previous review.

Hoffman, 63, was convicted of First-Degree Murder in 1981 in Hennepin County and sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole. The sentencing law in place at that time required parole consideration after the offender served a minimum period of at least 17 years. Hoffman was denied parole in 1994 and again in 2000.

The corrections commissioner has statutory responsibility for parole decisions for offenders receiving life sentences with the possibility of parole.

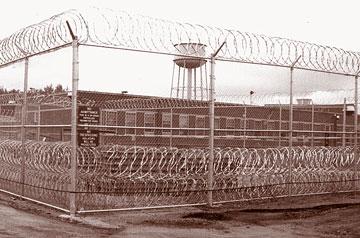

Hoffman is currently incarcerated at the Minnesota Correctional Facility-Moose Lake, a medium-custody prison housing approximately 1,025 adult male inmates.

|

|

|

| Click photo for the Kare11 Jan. 22, 2010 Video |

|

|

|

| Carol Hoffman's family members |

|

|

|

| Family members hold a picture of Carol Hoffman |

|

|

Minn. man who murdered, dismembered wife in 1980 denied parole

2010 by KARE - Filed Under Local News

|

ST. PAUL, Minn. -- Convicted murderer David Hoffman will not be released on parole after being convicted of killing his wife three decades ago. It is the third time the Minnesota Department of Corrections parole panel has rejected parole for Hoffman.

The panel held a review Monday in St. Paul. Carol Hoffman's family was in attendance, vowing to continue the fight to keep Hoffman behind bars. They had an opportunity to speak with panel members before they made their decision.

A photo of Carol Hoffman's high school graduation is timeless and so is the pain her family feels 30 years after Carol was murdered by her husband David.

"Carol was sweet person," says Roger Stebbins, Carol's brother. "Part of our heart went the day she went."

In August 1980, at their home in Corcoran, David Hoffman strangled his wife, and then dismembered her body. He first tried to put Carol's remains in the garbage disposal and then ultimately dumped her body in Weaver Lake.

"She did not deserve to die that way," Roger said.

All of these years later, Carol's family still gives voice to her memory. David Hoffman is serving a life sentence at Moose Lake prison, but he is still eligible for parole. Carol's family says he's shown no remorse.

"I do not want him let out. I do not want him let out," says Carol's mother Phyllis.

Carol Hoffman's family has pleaded before with the Department of Corrections to keep David Hoffman in prison. He has been denied parole twice before, once in 1994 and again in 2000.

"When we have to relive this over and over and over again, that hurt comes back so strong," says Catherine Stebbins, Carol's sister.

Before this latest parole eligibility review, Carol's family took their message online, producing a YouTube video and urging people to sign a petition they hoped would keep Hoffman locked up for good.

"When the judge said life that's what it meant as far as I'm concerned," Roger says.

"She didn't get to see her daughter walk down the aisle and get married. She didn't get to be there for her three grandsons," says Catherine.

Friends have said that Hoffman has been a model prisoner, is remorseful for what he did and should receive parole. As part of the parole review, Hoffman appeared by teleconference from Moose Lake. The review was not open to the public.

|

Keep David Hoffman locked up

Carol's family took their message online, producing a YouTube video 2010.

|

35 years later, family fights to keep killer in prison

|

|

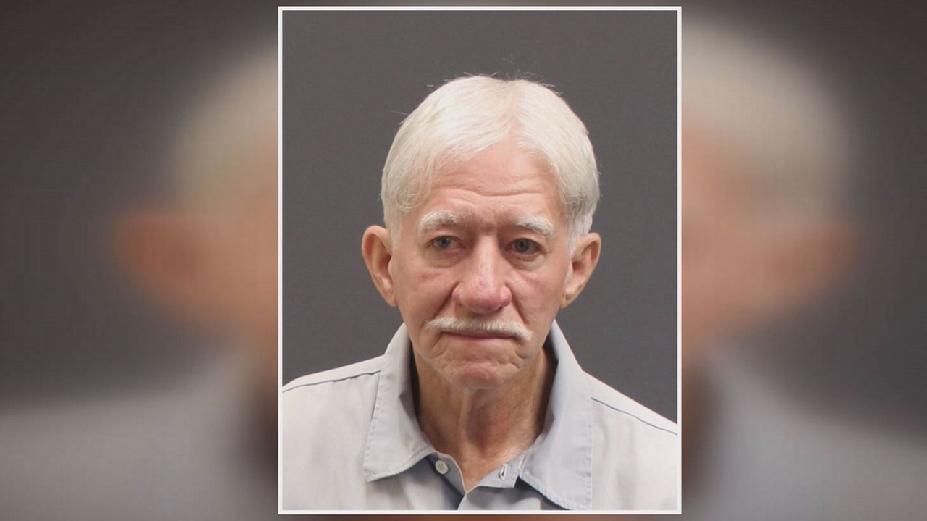

| David Hoffman 2016 - Click photo for Fox News Video April 3rd, 2016 A Must See! |

|

|

Pioneer Press Newpaper

April 14th, 2016

|

David Hoffman granted parole after 37 years, Carol Stebbins' family facing nightmare

|

|

| Click David's photo for the Fox News Live Video April 13th, 2016 |

|

|

ST. PAUL, Minn. (KMSP) - It was a devastating day for a family who has long fought to keep a killer in prison. But late Tuesday afternoon, the family of Carol Stebbins learned David Francis Hoffman will walk free in 2 years. In the more than 35 years Hoffman has spent in prison, they don't feel he's shown remorse, and they don't feel safe.

Hoffman, 69, was sent to prison in 1980 for murdering his wife in their home in Corcoran, Minn. He dismembered her body, putting parts down the garbage disposal, and the rest in a lake.

FOX 9 INVESTIGATORS - 35 years later, family fights to keep killer in prison

|

|

| Carol Hoffman's family members |

|

|

“We shouldn't have to go through this again,” said Stebbens’ niece, Charity Larsen. “It shouldn't even be an issue. He shouldn't have a second chance. Carol never had a second chance.”

This is actually Hoffman's 5th chance, because under 1980 law, parole review for first degree murder came up after only 17 years. Carol's extended family waited as 5 family members pled their case to the parole board for the 5th time. 30 minutes later, they emerged with the worry that maybe this time, he'll get out.

“We're terrified. Terrified not just for us, not for our family, but terrified for the public.”

As is custom after each hearing, the family went to Carol's gravesite in Anoka to wait for the news with the most fear they've felt yet.

“I'd be afraid I'd be the first one he's going to come after, because we kept him in there,” said Phyllis Stebbins, Carol’s mother.

They would learn late Tuesday afternoon that Hoffman is indeed being paroled. He'll serve 2 more years, followed by intense supervised release in April 2018. Carol's family plans to somehow keep fighting to keep him in.

|

Helen Catherine (Behrenbrinker) Hoffman-Ulvinen

|

|

Description

The evidence did not show beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant was guilty of active conduct sufficient to convict her of first degree murder under Minn. Stat. ? 609.05 (1980).

|

STATE v. ULVINEN

STATE of Minnesota, Respondent, v. Helen Catherine ULVINEN, Appellant.

Supreme Court of Minnesota.

December 17, 1981.

Appellant was convicted of first degree murder pursuant to Minn.Stat. § 609.05, subd. 1 (1980), imposing criminal liability on one who "intentionally aids, advises, hires, counsels, or conspires with or otherwise procures" another to commit a crime. We reverse.

Carol Hoffman, appellant's daughter-in-law, was murdered late on the evening of August 10th or the very early morning of August 11th by her husband, David Hoffman. She and David had spent an amicable evening together playing with their children, and when they went to bed David wanted to make love to his wife. However, when she refused him he lost his temper and began choking her. While he was choking her he began to believe he was "doing the right thing" and that to get "the evil out of her" he had to dismember her body.

After his wife was dead, David called down to the basement to wake his mother, asking her to come upstairs to sit on the living room couch. From there she would be able to see the kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom doors and could stop the older child if she awoke and tried to use the bathroom. Appellant didn't respond at first but after being called once, possibly twice, more she came upstairs to lie on the couch. In the meantime David had moved the body to the bathtub. Appellant was aware that while she was in the living room her son was dismembering the body but she turned her head away so that she could not see.

After dismembering the body and putting it in bags, Hoffman cleaned the bathroom, took the body to Weaver Lake and disposed of it. On returning home he told his mother to wash the cloth covers from the bathroom toilet and tank, which she did. David fabricated a story about Carol leaving the house the previous night after an argument, and Helen agreed to corroborate it. David phoned the police with a missing person report and during the ensuing searches and interviews with the police, he and his mother continued to tell the fabricated story.

On August 19, 1980, David confessed to the police that he had murdered his wife. In his statement he indicated that not only had his mother helped him cover up the crime but she had known of his intent to kill his wife that night. After hearing Hoffman's statement the police arrested appellant and questioned her with respect to her part in the cover up. Police typed up a two-page statement which she read and signed. The following day a detective questioned her further regarding events surrounding the crime, including her knowledge that it was planned.

Appellant's relationship with her daughter-in-law had been a strained one. She moved in with the Hoffmans on July 26, two weeks earlier to act as a live-in babysitter for their two children. Carol was unhappy about having her move in and told

friends that she hated Helen, but she told both David and his mother that they could try the arrangement to see how it worked.

On the morning of the murder Helen told her son that she was going to move out of the Hoffman residence because "Carol had been so nasty to me." In his statement to the police David reported the conversation that morning as follows:

A. Sunday morning I went downstairs and my mom was in the bedroom reading the newspaper and she had tears in her eyes, and she said in a very frustrated voice, I've got to find another house. She said, Carol don't want me here, and she said, I probably shouldn't have moved in here. And I said then, Don't let what Carol said hurt you. It's going to take a little more period of readjustment for her. Then I told mom that I've got to do it tonight so that there can be peace in this house.Q. What did you tell your mom that you were going to have to do that night?A. I told my mom I was going to have to put her to sleep.Q. Dave, will you tell us exactly what you told your mother that morning, to the best of your recollection?A. I said I'm going to have to choke her tonight and I'll have to dispose of her body so that it will never be found. That's the best of my knowledge.Q. What did your mother say when you told her that?A. She just — she looked at me with very sad eyes and just started to weep. I think she said something like it will be for the best.

David spent the day fishing with a friend of his. When he got home that afternoon he had another conversation with his mother. She told him at that time about a phone conversation Carol had had in which she discussed taking the children and leaving home. David told the police that during the conversation with his mother that afternoon he told her "Mom, tonight's got to be the night."

Q. When you told your mother, Tonight's got to be the night, did your mother understand that you were going to kill Carol later that evening?A. She thought I was just kidding her about doing it. She didn't think I could. * * *Q. Why didn't your mother think that you could do it?A. * * * Because for some time I had been telling her I was going to take Carol scuba diving and make it look like an accident.Q. And she said?A. And she always said, Oh, you're just kidding me. * * *Q. But your mother knew you were going to do it that night?A. I think my mother sensed that I was really going to do it that night.Q. Why do you think your mother sensed you were really going to do it that night?A. Because when I came home and she told me what had happened at the house, and I told her, Tonight's got to be the night, I think she said, again I'm not certain, that it would be the best for the kids.

Appellant raises issues concerning the denial of her constitutional right to confrontation, the admissibility of hearsay testimony of statements of the deceased, the admission of the statement of her son and the sufficiency of the evidence. We address only the issues of the prejudicial nature of the admission of statements of the deceased regarding her feelings about appellant and the sufficiency of the evidence to support a verdict of first degree murder.

The statements to which appellant objects were introduced at trial through the testimony of friends and neighbors of the deceased, and related to her feelings about her mother-in-law. The comments of the deceased indicated that she hated her mother-in-law, was unhappy about her moving in, did not believe that she was a good babysitter and was afraid that she or the children would be poisoned and that it was

therefore necessary to hide all the dangerous substances in the house. They were admitted as state of mind exceptions to the hearsay rule. Carol Hoffman's state of mind was not at issue in the case. These statements, which were extremely prejudicial, were likely to lead the jury to conclude that the deceased was afraid of her mother-in-law and therefore appellant probably disliked her enough to kill her. The admission of these statements was prejudicial error which would normally require a new trial. However, our decision that the evidence is insufficient to support a verdict of first degree murder requires instead that we reverse without remanding for a new trial.

In reviewing a claim of sufficiency of the evidence we must determine whether, under the facts in the record and any legitimate inferences that can be drawn from them, a jury could reasonably conclude that the defendant was guilty of the offense charged. State v. Merrill, 274 N.W.2d 99 (Minn.1978). The evidence must be viewed in the light most favorable to the prosecution and it is necessary to assume that the jury believed the state's witnesses and disbelieved any contrary evidence. State v. Wahlberg, 296 N.W.2d 408 (Minn. 1980).

It is well-settled in this state that presence, companionship, and conduct before and after the offense are circumstances from which a person's participation in the criminal intent may be inferred. State v. Parker, 282 Minn. 343, 164 N.W.2d 633 (1969). The evidence is undisputed that appellant was asleep when her son choked his wife. She took no active part in the dismembering of the body but came upstairs to intercept the children, should they awake, and prevent them from going into the bathroom. She cooperated with her son by cleaning some items from the bathroom and corroborating David's story to prevent anyone from finding out about the murder. She is insulated by statute from guilt as an accomplice after-the-fact for such conduct because of her relation as a parent of the offender. See Minn.Stat. § 609.495, subd. 2 (1980). The jury might well have considered appellant's conduct in sitting by while her son dismembered his wife so shocking that it deserved punishment. Nonetheless, these subsequent actions do not succeed in transforming her behavior prior to the crime to active instigation and encouragement. Minn.Stat. § 609.05, subd. 1 (1980) implies a high level of activity on the part of an aider and abettor in the form of conduct that encourages another to act. Use of terms such as "aids," "advises," and "conspires" requires something more of a person than mere inaction to impose liability as a principal.

The evidence presented to the jury at best supports a finding that appellant passively acquiesced in her son's plan to kill his wife. The jury might have believed that David told his mother of his intent to kill his wife that night and that she neither actively discouraged him nor told anyone in time to prevent the murder. Her response that "it would be the best for the kids" or "it will be the best" was not, however, active encouragement or instigation. There is no evidence that her remark had any influence on her son's decision to kill his wife. Minn.Stat. § 609.05, subd. 1 (1980), imposes liability for actions which affect the principal, encouraging him to take a course of action which he might not otherwise have taken. The state has not proved beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant was guilty of anything but passive approval. However morally reprehensible it may be to fail to warn someone of their impending death, our statutes do not make such an omission a criminal offense.1

David told many people besides appellant of his intent to kill his wife but no

one took him seriously. He told a co-worker, approximately three times a week that he was going to murder his wife, and confided two different plans for doing so. Another co-worker heard him tell his plan to cut Carol's air hose while she was scuba diving, making her death look accidental, but did not believe him. Two or three weeks before the murder, David told a friend of his that he and Carol were having problems and he expected Carol "to have an accident sometime." None of these people has a duty imposed by law, to warn the victim of impending danger, whatever their moral obligation may be. The state has not proved beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant was guilty of any of the activities enumerated in the statute. Appellant's comment is not sufficient additional activity on her part to constitute planning or conspiring with her son. She did not offer advice on how to kill his wife, nor offer to help him. She did not plan when to accomplish the act or tell her son what to do to avoid being caught. She was told by her son that he intended to kill his wife that night and responded in a way which, while not discouraging him, did not aid, advise, or counsel him to act as he did. Where, as here, the evidence is insufficient to show beyond a reasonable doubt that appellant was guilty of active conduct sufficient to convict her of first degree murder under Minn.Stat. § 609.05, subd. 1 (1980), her conviction must be reversed.

YETKA, Justice (concurring specially).

I concur in the finding that it is difficult to justify a conviction for first degree murder — perhaps third degree murder or manslaughter is more appropriate.

However, I disagree with that portion of the majority opinion which finds the statements by the deceased inadmissible. I believe the trial court properly admitted the statements for the reasons it set forth.

|

| Helen Catherine (Behrenbrinker) Hoffman-Ulvinen |

|

|

| Burial: Helen Catherine (Behrenbrinker) Hoffman-Ulvinen Click for Info... |

|

|

|

STATE v. HOFFMAN

STATE of Minnesota, Respondent, v. David Francis HOFFMAN, Appellant.

Supreme Court of Minnesota.

December 30, 1982.

David Hoffman was convicted of first degree murder in the brutal slaying of his wife. During interrogation he had implicated his mother who was charged with conspiracy to commit first degree murder. We reversed her conviction inState v. Ulvinen, 313 N.W.2d 425 (Minn.1981). Hoffman contends his conviction should be reversed because of the improper admission of a confession, improper jury instructions regarding the defense of mental illness; failure to instruct on the lesser included offense of first degree manslaughter, improper jury conduct, and improper prosecutorial final argument. We affirm.

The facts relating to the murder and dismemberment of Carol Hoffman are set forth in State v. Ulvinen, 313 N.W.2d at 425, 426, 427 (Minn.1981). After her death Hoffman filed a missing person report with the Corcoran Police Department. Thereafter he was interviewed by the Hennepin County Sheriff's Office. A search was conducted of the area where Carol was thought to have disappeared and David Hoffman participated in the search.

During the time after Carol's death David began to believe that the end of the world was coming. He became very emotional and experienced a religious conversion. David again met with the Hennepin County Sheriff's deputies. He was advised of his constitutional rights at the outset of the interview. He asked each detective if he believed in the Lord and then told them what actually had happened on the night Carol died. He described in detail how he had killed Carol and disposed of her body. The detectives testified that David was calm throughout the interview although he occasionally became emotional. He made a written confession which he read, corrected and signed.

The officers prepared a search warrant for the house and boat. David agreed to take the detectives to Weaver Lake and point out the location where he had dropped the bags. The body of Carol Hoffman subsequently was recovered. David was charged by indictment with first degree murder. He pled not guilty and not guilty by reason of mental illness. Upon defendant's motion for change of venue the trial was moved to the Olmstead County Court-house in Rochester. On February 11, 1981 the jury returned a verdict of guilty on the first degree murder charge. On February 18, 1981 the trial court sentenced David Hoffman to life imprisonment.

The issues presented are:

1. Was Hoffman's confession voluntary?

2. Was Hoffman's right to assert mental illness as a defense infringed upon by the trial court's instructions to the jury?

3. Should the lesser included offense of first degree manslaughter have been submitted to the jury?

4. Was there improper jury conduct?

5. Was there improper final prosecutorial argument?

1. A Rasmussen Hearing was held on January 27, 1981. At that time evidence was presented relating to the defense motion to suppress the written statement made by David Hoffman to the Hennepin County Sheriff's deputies on August 19, 1980. After hearing the testimony of the witnesses, the trial court found that Hoffman

had been properly advised of his Miranda rights and had voluntarily waived them. The motion to suppress was denied. The defendant argues that his confession was not voluntarily made because he was not mentally competent at the time he spoke to the detectives and signed the written confession.

The evidence relating to the confession included the testimony of the three officers who were present when David Hoffman gave his statement detailing the killing of his wife Carol. Detective Huckaby testified that David was advised of hisMiranda rights prior to making his confession. David asked each officer if he believed in the Lord and all three responded in the affirmative. He then proceeded to tell them how he had strangled his wife, dismembered her body, and disposed of the body in Weaver Lake.

David was calm up to the point where he asked the officers about their belief in the Lord. He then began to get more emotional and was described as being on the verge of tears. He broke down four or five times during his oral statement when he referred to his children and his mother. He was responsive during questioning and appeared to understand what was said to him. According to Detective Huckaby, David was in a state of "relieved calm" after making the oral confession.

Detective Sonenstahl, the officer who took David's written statement, testified that during that interview David was willing to answer questions and did not have difficulty understanding what was said to him. At the end of his written statement David was asked if there was anything he wished to add. He then mentioned the eruption of Mount St. Helen's, relating it to the fact that his mother's name was Helen and saying that he felt the end of the world was near. David was then told to read each page of the statement and make corrections, which he did.

Two psychiatrists testified regarding the defendant's mental state. Both doctors interviewed David Hoffman in the Hennepin County Detention Center a day or two after his confession. At that time Dr. Darel Hulsing diagnosed David as psychotically depressed. He stated that David was suffering from delusional thinking that may have been present for some time. However, on cross-examination Dr. Hulsing testified that psychotic depression would not prevent David from knowing his surroundings and the circumstances in which he found himself or participating intelligently in a conversation with the police officers.

Dr. Stephans testified that based on his interviews with David Hoffman, he diagnosed David as suffering from acute psychosis. In response to a hypothetical question, Dr. Stephans stated that in his opinion David was not competent to understand the charges against him and did not have the capacity to understand his rights on the day he made his confession.

Additional evidence concerning the defendant's mental state at the time of his confession came from two attorneys who visited him in jail on August 21. John McVay testified that when he asked David if he wanted to talk to them about his situation, David replied that he though that the police officers and the Lord would be his lawyers but if they wished to be his attorneys that would be okay too. McVay related portions of his conversation with David wherein David made inappropriate comments. He characterized David's mental state by stating that he did not feel that he was getting through to David. Mr. McVay's partner, Thomas O'Connor, testified that in his opinion David Hoffman wasn't aware of the seriousness of the situation or what was happening to him.

The defendant himself testified at the Rasmussen Hearing. He stated that he could not remember giving an oral statement to the detectives and could only remember parts of the written interview. He also described his thoughts on August 19 concerning the end of the world and the appearance of God. He said that he wanted to tell the detectives what he'd done so Carol's body could be recovered and her soul could go to heaven. On cross-examination David testified that he told the detectives

what had happened, that he was not coerced, that he understood the detective's questions and that he knew that he was confessing to having killed a human being.

The state has the burden of establishing the voluntary nature of the confession by a fair preponderance of the evidence. State v. Wajda,296 Minn. 29, 206 N.W.2d 1 (1973). The finding of the trial court as to admissibility of the confession will not be reversed unless it is clearly erroneous, but this court can make an independent determination of the voluntariness of the confession based on the record. State v. Hardimon, 310 N.W.2d 564, 567 (Minn.1981).

Hoffman does not contend that improper police conduct was used in obtaining his confession or that his conviction is not based on reliable evidence. Rather, he contends that the constitutional due process issue arises in this case because of our concern that a defendant's confession be the product of his free and rational choice. There is conflicting evidence on the question of whether the defendant was capable of making a voluntary confession. The question is a close one because, while Hoffman was capable of understanding the officer's questions and responding to them, he may not have been competent to understand the seriousness of his situation and to make a rational decision to waive his right to counsel and his right to remain silent.

There is no indication that David Hoffman was pressured into making a statement by the police or that the circumstances surrounding the interview compelled him to speak. In fact, the evidence shows that he was extremely cooperative and willing to tell the police how he had killed his wife and disposed of the body. He appeared to be coherent and able to understand where he was and what the police were saying to him. However Dr. Stephans testified that because David was suffering from acute psychosis he was not competent to understand the charges against him or his constitutional rights. In addition, Hoffman's conversation with the attorneys indicates a certain inability to grasp the reality of the situation he was in.

Despite the existence of some testimony to the contrary, we find, after independently evaluating the record, that the prosecution established the voluntariness of Hoffman's confession by a fair preponderance of the evidence. The trial court's refusal to suppress the confession was not clearly erroneous.

2. Hoffman claims error in the trial court's instructions to the jury regarding evaluation of evidence relative to mental capacity. The court gave the following instruction over defense objection:

[Y]ou are to consider the testimony of the various witnesses as to the defendant's mental state at the time of the death of Carol Hoffman solely on the question of whether the defendant knew the nature of his act and whether he knew his act was wrong.You are not to consider this testimony on the issues of the premeditation and intent of the defendant to affect the death of Carol Hoffman. That is a separate and independent defense.

The challenge to this instruction necessarily requires this court to consider the nature and scope of the mental illness defense. We have never directly considered either issue. With reference to the nature of the defense, we must first consider whether the right asserted by the defendant is a constitutional right or whether it is a right conferred by statute. Other states which have considered this issue have determined that the right involved is a constitutional right. We agree.

In State v. Strasburg, 60 Wn. 106, 110 P. 1020 (1910), the Supreme Court of Washington declared a state statute unconstitutional which provided that insanity was not a defense to a crime. The court found the insanity defense to be a part of the common law which existed before its state's constitution and was "unimpaired by judicial decision or legislative enactment." Id. at 108, 110 P. at 1022. The statute deprived the defendant of liberty without due process of law primarily because it deprived him of the right to trial by jury. It stated:

Whatever the power may be in the Legislature to eliminate the element of intent from criminal liability, we are of the opinion that such power cannot be exercised to the extent of preventing one accused of crime from invoking the defense of his insanity at the time of committing the Act charged, and offering evidence thereof before the jury. One so accused had this right at the time of the adoption of our Constitution, and we are of the opinion that the question, is so inherently related to the guilt or innocence of all accused persons, that it cannot be now taken away from them without violating these guarantees of the Constitution.

Id.

In Mississippi, a statute stated that insanity was not a defense to a crime, but could be considered as a mitigating factor in sentencing. Sinclair v. State, 161 Miss. 142, 132 So. 581 (1931), held that such a statute violated the due process clause of the state and federal constitutions, and the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Similarly, Colorado has recognized that any statute which provides that insanity is no defense to a criminal charge is unconstitutional. Ingles v. People, 92 Colo. 518, 22 P.2d 1109 (1933).

Most recently, Louisiana declared that juveniles have a constitutional right to present evidence of insanity in a juvenile prosecution, even though it is a civil proceeding. In re Causey, 363 So.2d 472(La. 1978). The court stated that "the denial of the right to plead insanity, with no alternative means of exculpation or special treatment for an insane person unable to understand the nature of his act, violates the concept of fundamental fairness implicit in the due process guaranties."Id. at 474.

The United States Supreme Court has not addressed the question. However, recent federal cases have spoken of the insanity plea in terms indicating that the right to assert it has constitutional dimensions of a due process nature. See e.g. Busynski v. Oliver, 538 F.2d 6 (1st Cir.), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 984, 97 S.Ct. 503, 50 L.Ed.2d 596 (1976); Hill v. Lockhart, 516 F.2d 910(8th Cir.1975); Ramer v. United States, 390 F.2d 564 (9th Cir.1968). See also Wharton's Criminal Law and Procedure, § 38 at 82-83 (1957 & Supp.1979) (regarded as an essential constitutional right).

Minnesota has recognized this concept in dictum. In State v. Rawland, 294 Minn. 17, 199 N.W.2d 774 (1972), the court stated:

It has been said that a statute providing that insanity shall be no defense would be unconstitutional as a violation of due process of law and the right to trial by jury.

Id. at 38, 199 N.W.2d at 786. In State v. Billings,55 Minn. 467, 57 N.W. 794 (1894), the court examined the constitutionality of Minnesota's civil commitment statute. In dictum it stated that there are certain fundamental rights that the Legislature cannot take away. It stated:

* * * in judicial proceedings, due process of law requires notice, hearing, and judgment. These words * * * do not mean anything which the legislature may see fit to declare to be due process of law, for there are certain fundamental rights which our system of jurisprudence has always recognized, which not even the legislature can disregard, in proceedings by which a person is deprived of life, liberty, or property, and one of these is notice before judgment in all judicial proceedings. * * * it may be stated generally that due process of law requires that a party shall be properly brought into court, and that he shall have an opportunity, when there, to prove any fact which, according to the constitution and the usages of the common law, would be a protection to him or to his property.

Id. at 474, 57 N.W. at 795. (emphasis supplied).

We now hold that a defendant has a due process constitutional right to assert the defense of mental illness under both the state and federal constitutions. U.S.Const. Amend., XIV, § 1; Minn.Const. art. I, § 7.

In State v. Bouwman, 328 N.W.2d 703(Minn.1982), released today, together

with this opinion, we have held that the defendant has no right to present psychiatric evidence as to diminished responsibility. The defendant's right to present evidence as to mental capacity occurs as part of his case. The issue of the defendant's mental capacity is not involved in the state's evidence where it must establish that the defendant committed the act charged and further establish the intent or premeditation of the defendant if either are an element of the particular crime.

3. Thus the trial court correctly advised the jury that it should consider the evidence relating to the defendant's state of mind in the scope of the mental illness defense as defined in Minn.Stat. § 611.026 (1980) which states as follows:

No person shall be tried, sentenced, or punished for any crime while mentally ill or deficient so as to be incapable of understanding the proceedings or making a defense, but he shall not be excused from criminal liability except upon proof that at the time of committing the alleged criminal act he was laboring under such a defect of reason, from one of these causes, as not to know the nature of his act, or that it was wrong.

This statute is a codification of the common law rule first adopted in 1843. M'Naghten's Case, 10 Clark & Finnelly 200, 8 Eng.Rep. 718 (H.L. 1843). An extensive review of its legal background appears in State v. Rawland, 294 Minn. 17, 29-36, 199 N.W.2d 774, 781-84 (1972). As indicated there, various courts and institutions have sought other means of coping with the problem of the insanity defense. Minnesota has consistently resisted all efforts to effectuate any basic change. As reflected in the Rawlanddecision, the legislative changes that have occurred led to evaluation of the whole person in determining the propriety of the insanity defense in a particular case. Admittedly, retention of theM'Naghten rule is a minority position.

Since the presentation of evidence of mental illness is a right of constitutional dimension, this court can define the scope of the defense. At this time, however, we need not consider this question since we are satisfied that theM'Naughten rule provides a fair and just means of evaluating the actions of a defendant who claims the defense of mental illness.

We do observe that the language of the instruction is misleading in that it refers to intent and premeditation as defenses rather than elements of crime charged which the state must prove. When the jury instructions are considered as a whole, that language, though confused, was not prejudicial to the defendant.

4. The problem which the trial court dealt with in this case will not arise if the defendant elects to bifurcate the trial as provided for in our Rules of Criminal Procedure. Minn.R.Crim.P. 20.02, subd. 6(2). There the first part of the trial will be directed solely to whether or not the state has sustained its burden of proof as to the guilt of the defendant. The second part of the trial will be directed solely to a determination of whether the defendant has sustained the burden of establishing the defense of mental illness.

In order to avoid confusion in the conduct of a trial where the defendant has entered a plea of not guilty by reason of mental illness, but has not elected to bifurcate the trial, we now direct that the following proceedings will occur. The state will proceed with its case and rest. The defense will proceed to introduce any evidence, except psychiatric evidence relating to the capacity of the defendant, relative to the credibility of the evidence introduced by the state from which it seeks to establish that the defendant committed the act and further seeks to infer that the defendant had the required intent or premeditation required under the specific crime or crimes for which the defendant is charged. The defense shall rest provisionally as to this part of the evidence and the state may rebut evidence introduced by the defense. When both sides have rested on these issues

the defendant shall proceed to introduce evidence as to his or her defense of mental illness.1

The proceedings in the second stage of a criminal trial, whether bifurcated or separated as herein provided, shifts to the defendant the burden of establishing by a fair preponderance of the evidence that he or she lacked the capacity to form the requisite intent to commit the crime charged. Minn.Stat. § 611.025 (1980). Expert evidence is appropriate to assist the jury in making its determination. The accused's mental capacity to formulate the requisite intent presents an opportunity for the presentation of relevant medical testimony, but the ultimate issue involves his criminal responsibility. It is solely the function of the jury to determine the ultimate question as to whether or not the appropriate capacity exists. Thus a strong argument can be made that the expert witness should not be allowed to render an opinion as to the capacity of the defendant to have the requisite intent or premeditation. As a practical matter, however, we will permit qualified experts to answer this ultimate question so long as an appropriate instruction is given to the jury emphasizing that it is their function to make this determination and any opinions on these questions are not binding upon them. We adopt the view of the court in Bethea v. United States,365 A.2d 64, 86 n. 46 (D.C.1976), where it is stated:

The unspoken assumption underlying the rationale in Brawner (United States v. Brawner, 153 U.S.App.D.C. 1, 471 F.2d 969 (1972) (en banc)) is that the separate medical and legal models of the human mind are sufficiently congruent to warrant the conclusion that expert testimony based upon the former necessarily would be relevant to the legal question of whether the accused's mental condition satisfied the concept of mens rea. We do not quarrel with the notion that psychiatric testimony is of general relevance to the issue of responsibility; that is, that the ability of the accused to function normally (as defined by the medical model) will bear upon the applicability of the inferential analysis by which mens rea ordinarily is determined. Care must be exercised, however, to distinguish such general relevancy from the unwarranted additional assumption that the psychiatric sciences are capable of direct proof of the existence of the necessary mental state as defined by law.

When the defense has rested, the state has a right to present rebuttal expert evidence as to the capacity of the defendant to form the requisite intent or premeditation. Its experts may also answer the ultimate question subject to the same cautionary jury instruction.

5. In a unitary trial, the court shall instruct the jury that evidence as to mental capacity of the defendant is to be considered only in the second stage of the trial and is not to be considered when evaluating evidence presented in the first stage of the trial as to the fact of intent as it may be inferred from the evidence.

The jury should further be instructed that they should first determine if the state has proved all of the elements of the offense charged beyond a reasonable doubt before proceeding to consider the evidence relating to the defense of mental illness. Leland v. Oregon, 343 U.S. 790, 72 S.Ct. 1002, 96 L.Ed. 1302 (1952).

6. Hoffman contends that the trial court erred in denying his requested instruction on the lesser included offense of first degree manslaughter. He alleges that under the standard established inState v. Leinweber, 303 Minn. 414, 228 N.W.2d 120 (1975), the evidence would reasonably support a not guilty verdict on the first and second degree murder charges and a conviction on the first degree manslaughter charge.

The portion of the first degree manslaughter statute applicable to this case states that one is guilty of that charge if

one "intentionally causes the death of another person in the heat of passion provoked by such words or acts of another as would provoke a person of ordinary self-control under like circumstances." Minn. Stat. § 609.20, subd. 1 (1980). In State v. Leinweber, this court discussed at length the standard for submitting that charge in a murder case. In that case the defendant was charged with second degree murder for the shooting death of his wife and was convicted of the lesser offense of third degree murder. The defendant claimed that he shot his wife by accident while cleaning his gun. On appeal this court found that because there was evidence of emotional strain and habitual arguing between the defendant and his wife, it was error for the trial court to refuse to give the requested instruction on first degree manslaughter. See also State v. McDonald, 312 Minn. 320, 251 N.W.2d 705 (1977) (test is whether there is rational basis for verdict acquitting defendant of greater offense and convicting of lesser offense).

The issue here is a close one, in light of the standard set forth in Leinweber. As in Leinweber,there was evidence of marital discord between David and Carol Hoffman, particularly surrounding the issue of David's mother living with the Hoffmans. David testified that when Carol rejected his sexual advances and told him, "Why don't you go downstairs and fuck your fat mama," he lost control and began to choke her. Also, similar to the facts in Leinweber, there was evidence here of premeditation, including statements made by Hoffman to co-workers and to his mother prior to Carol's death that he planned to kill his wife. That evidence would not necessarily be inconsistent with murder in the heat of passion, however, because a jury could find that while David fantasized about killing Carol he was actually provoked to do so by her words on August 10th.

The manslaughter statute requires that the provocation be such "as would provoke a person of ordinary self-control under like circumstances." The words and acts of Carol Hoffman, while insulting, do not rise to the level of provocation for murder for a person of ordinary self-control, even given the increasing tension in the Hoffman marriage. In addition, the fact that the jury was instructed on both first and second degree murder and found the defendant guilty of first degree murder indicates that they believe that the killing was premeditated and therefore not committed in the heat of passion. The failure to give the manslaughter instruction did not prejudice the defendant. See State v. Wahlberg, 296 N.W.2d 408, 417-18 (Minn. 1980).

7. The claim of improper jury contact is not sustained by the record. During the course of the trial the court brought to the attention of counsel the fact that one of the jurors, a barber, had been contacted by one of his customers and that in the course of his conversations with her the customer asked the juror if he had seen any pictures during the trial. The juror told the woman that he couldn't talk about the trial and hung up on her. The judge told the attorneys that he would examine the juror and if it appeared that the incident would be a problem, he would call the attorneys in.

The juror was interviewed by the trial court outside the presence of the attorneys. Defense counsel made a motion to have the jurors examined in the presence of counsel and to have the juror who was contacted stricken. The trial judge denied the motion because he viewed the conversation as "extremely inconsequential" and because he felt that it would not influence the juror's decision. We agree.

8. Finally, Hoffman contends that portions of the prosecutor's final argument, in which the prosecutor implied that his mental illness defense was contrived, prejudiced his right of a fair trial. The standard for granting a new trial based upon prosecutorial misconduct is that it is justified "only where the misconduct, viewed in the light of the whole record, appears to be inexcusable and so serious and prejudicial that defendant's right to a fair trial was denied."State v. Wahlberg, 296 N.W.2d 408, 420 (Minn.1980). The remarks made

and implications raised by the prosecutor here do not rise to the level requiring a new trial.

Affirmed.

SCOTT, Justice (concurring specially).

Rather than create new untested procedure that will cast us onto uncharted waters and surely compound the very confusion that we are striving to eliminate, I would require mandatory bifurcation when a plea of not guilty by reason of mental illness or mental deficiency is entered. This tested procedure is already outlined in Rule 20, Minn.R.Crim.P.

PETERSON, Justice.

I agree with the view of Justice Scott.

KELLEY, Justice.

I join in the concurring opinion of Justice Scott.

WAHL, Justice (concurring specially).

I do not disagree with the result in this case. However, for reasons set out in my dissent inState v. Bouwman, 328 N.W.2d 703 (Minn.1982), released today, I strongly disagree with the holding of the majority that the trial court committed no error by instructing the jury that the testimony of defense witnesses as to the defendant's mental state at the time of the death of Carol Hoffman could not be considered on the issues of premeditation and intent but only on the question of whether the defendant knew the nature of his act and whether he knew the act was wrong.

While the instruction was not prejudicial to defendant, there being ample evidence otherwise of premeditation and intent, it is, to my mind, an incorrect statement of the law. To hold that a defendant charged with murder in the first degree may not offer relevant and competent expert psychiatric opinion testimony on the issues of premeditation and specific intent is to violate the defendant's constitutional right to present evidence. Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14, 18-19, 87 S.Ct. 1920, 1922-23, 18 L.Ed.2d 1019 (1967); Hughes v. Mathews, 576 F.2d 1250, 1255-56 (7th Cir.1978), cert. dismissed sub nom. Israel, Warden v. Hughes, 439 U.S. 801, 99 S.Ct. 43, 58 L.Ed.2d 94 (1978).

I also strongly disapprove of the majority's wholesale amendment of the Rules of Criminal Procedure with regard to the trial of criminal cases where the defendant has entered a plea of not guilty by reason of mental illness but has not elected to bifurcate the trial as provided by Minn.R.Crim.P. 20. The new untested procedure will not only compound the confusion, as Justice Scott notes in his special concurrence, it will confound the criminal law bar, whose members have a right to expect that an amendment of such magnitude would go through the Criminal Rules Committee charged with monitoring those rules and be the subject of hearing and debate before this court before adoption.

|

|

| August 1980 |

|

|

|

| David Francis Hoffman |

|

|

|

| David Francis Hoffman |

|

| 2

0

1

6

|

|

| MINNESOTA CORRECTIONAL FACILITY - WILLOW RIVER/MOOSE LAKE |

|

|

Carol Lynn Stebbins-Hoffman

1953-1980

|

|

| Carol Lynn Stebbins 1970 |

|

|

|

| Carol Hoffman & family members 1980 |

|

|

Carol Hoffman had two daughters who were ages 3 years and 9 months when was killed in August 1980. The murder was one of the most notorious in Hennepin County history at the time, according to police.

|

Forest Hill Cemetery

Located in Anoka, Minnesota

Carol Lynn Stebbins Hoffman's resting spot.

|

If tears could build a stairway and thoughts a memory lane I’d walk right up to heaven and bring you home again No Farewell words were spoken No time to say good-bye You were gone before I knew it And only God knows why.

My heart’s still active in sadness And secret tears still flow What it meant to lose you No one can ever know. But now I know you want us To mourn for you no more To remember all the happy times Life still has much in store.

Since you’ll never be forgotten I pledge to you today A hallowed place within my heart Is where you’ll always stay.

God knows why, with chilling touch, Death gathers those we love so much, And what now seems so strange and dim, Will all be clear, when we meet Him. I Knew you for a Moment

|

Carol Stebbins-Hoffman's family members

|

|

| Katherine "Kathy" Stebbins

Facebook page

|

|

|

| Carol Lynn Stebbins-Hoffman |

|

|

Carol Lynn Stebbins Hoffman

Oh my loving sister Carol you are so deeply loved and missed by your family, the justice system has failed but your family will continue to fight and be your voice. We know it will not bring you back, but it is the right thing to do cause we also know when it is our time to leave this world that someday we will be with you again. And until that time we will have done our best to honor and make things right for what is already wrong, we love you Carol Lynn Stebbins Hoffman always. Kathy Stebbins

|

|

| If tears could build a stairway and thoughts a memory lane I’d walk right up to heaven and bring you home again No Farewell words were spoken No time to say good-bye You were gone before I knew it And only God knows why.... |

|

| |

This is not justic for not just taking a life but for the dismemberment and trying to hide his real crime God help us all. Kathy Stebbins

|

|

| David Hoffman |

|

|

|

| WILLOW RIVER/MOOSE LAKE |

|

|

|

| MINNESOTA CORRECTIONAL FACILITY - WILLOW RIVER/MOOSE LAKE |

|

|

|

| MINNESOTA CORRECTIONAL FACILITY - WILLOW RIVER/MOOSE LAKE |

|

|

Willow River/Moose Lake Correctional Facility

Willow River/Moose Lake Correctional Facility are a level III medium custody facility and a level I minimum custody boot camp. Moose Lake is the medium custody facility that houses over 1,000 male offenders. Willow River is the minimum security boot camp that houses up to 180 minimum security inmates who are non-violent and qualify for early release. Inmates at Willow River are in a six month intensive program that combines education, substance abuse treatment, critical thinking development, and physical exercise. After six months, inmates at Willow River are put on six months supervised release.

|

|

| Minnesota's correctional system has four levels of classification, ranging from 2-5. |

|

|

|

| WILLOW RIVER/MOOSE LAKE |

|

|

| I wish you sweet sleep, my sister dear.

Although there's so much that you've left bare

I hate that you had to endure such pain

On my mind, your saddened eyes have left a stain.

I want to know what crossed your mind

Unspoken words you've left behind

Undone things we'll never do

No sharing thoughts you never knew.

A peace has fallen upon your head

A taste of sorrow we have been fed

It really is like a hole in our lives

One swiftly dug but carved out by knives.

But I have hope that those sleeping will rise

The Bible says that God will open their eyes.

No suffering, sickness, yes not even pain,

Those who did good, eternal life they'll gain.

So... sleep on my sister, sleep tight

For now with you the sky is night.

But after night will come daybreak

Therefore I will wait hoping to see you awake.

| |

|

| Katherine "Kathy" Stebbins (Carol Hoffman's Sister) |

|

|

Thanks for stopping by...

|

This website contains, in various sections, portions of copyrighted material not specifically authorized by the copyright owner. This material is used for educational purposes only and presented to provide understanding or give information for issues concerning the public as a whole. In accordance with U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. More Information

Information presented based on medical, news, government, and/or other web based articles or documents does not represent any medical recommendation or legal advice from myself or West Saint Paul Antiques. For specific information and advice on any condition or issue, you must consult a professional health care provider or legal advisor for direction.

I and West Saint Paul Antiques can not be responsible for information others may post on an external website linked here ~ or for websites which link to West Saint Paul Antiques. I would ask, however, that should you see something which you question or which seems incorrect or inappropriate, that you notify me immediately at floyd@weststpaulantiques.com Also, I would very much appreciate being notified if you find links which do not work or other problems with the website itself. Thank You!

Please know that there is no copyright infringement intended with any part of this website ~ should you find something that belongs to you and proper credit has not been given (or if you simply wish for me to remove it),

just let me know and I will do so right away.

|

Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

By using this website, West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, you are agreeing to use the site according to and in agreement with the above and following terms of use without limitation or qualification. If you do not agree, then you must refain from using the site.

The 'Terms of Use' govern your access to and use of this website and facebook pages associated with it. If you do not agree to all of the Terms of Use, do not access or use the website, or the facebook sites. By accessing or using any of them, you and any entity you are authorized to represent signify your agreement to be bound by the Terms of Use.

Said Terms of Use may be revised and/or updated at any time by posting of the changes on this page of the website. Your continued usage of the website, or the facebook site(s) after any changes to the Terms of Use will mean that you have accepted the changes. Also, any these sites themselves may be changed, supplemented, deleted, and/or updated at my sole discretion without notice; this establishes intellectual property rights by owner (myself).

It saddens me to include a Terms of Use for West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, but we all realize it is something that is necessary and must be done these days. By using the website, or facebook for West Saint Paul Antiques, you represent that you are of legal age and that you agree to be bound by the Terms of Use and any subsequent modifications. Your use of the West Saint Paul Antiques sites signify your electronic acceptance of the Terms of Use and constitute your signature to same as if you had actually signed an agreement embodying the terms.

|

|