Important Message

This Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

Will be at the bottom of most web pages!

Please read it before using this website.

Thank You

|

Thanks for stopping by...

|

|

| Travis' Letter From The Alamo |

|

|

|

|

| Remember The Alamo |

|

|

|

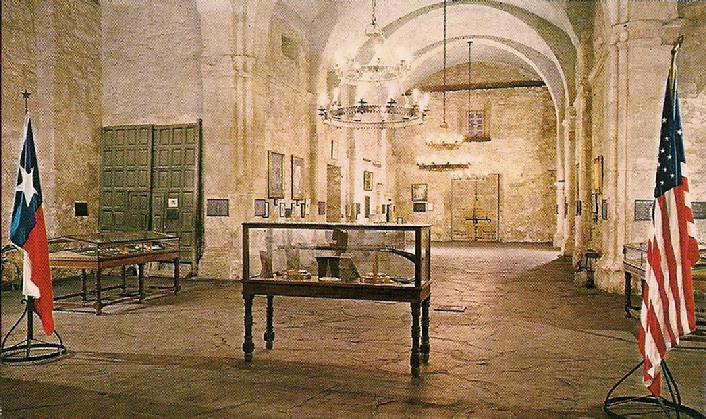

| The Interior of the Alamo |

|

|

|

| The Battle Of The Alamo |

|

|

The Battle of the Alamo (February 23 – March 6, 1836) was a pivotal point in the Texas Revolution. Following a twelve-day siege, Mexican troops under General Antonio López de Santa Anna launched an assault on the Alamo Mission in San Antonio de Béxar. All but two members of the small Texian garrison were killed. Santa Anna’s perceived cruelty inspired many Texas settlers and adventurers from the United States to join the Texian Army. Buoyed by a desire for revenge, the Texians, shouting “Remember the Alamo!”, defeated the Mexican Army at the Battle of San Jacinto several weeks later, ending the revolution.

During the first few months of the revolution, Texians had driven all Mexican troops out of Mexican Texas. After their departure, a poorly provisioned group of Texians attempted to convert the Alamo into a fortress. Several small parties of reinforcements arrived over the next few months, with the two largest led by eventual Alamo co-commanders James Bowie and William B. Travis. On February 23, Santa Anna led approximately 1,500 troops into Béxar as the first step in his campaign to retake Texas. The vastly outnumbered Texians asked for an honorable surrender and were denied. For the next twelve days, the two armies engaged in several small skirmishes, with minimal casualties. Reinforcements brought the Mexican army strength to 2,400 troops. Aware that his garrison could not withstand an attack by this large a force, Travis wrote multiple letters pleading for reinforcements and supplies. Two groups, totalling about 100 men, sucessfully entered the Alamo. An additional 400 Texians gathered in nearby Gonzales in a futile attempt to join Texian Colonel James W. Fannin, who had already aborted his reinforcement drive.

In the early morning hours of March 6 the Mexican army advanced on the Alamo. Their first two attacks were repulsed, but the Texians were unable to fend off a third. As Mexican soldiers scaled the walls, most of the Texian soldiers withdrew into interior buildings. Several small groups who were unable to reach these points attempted to escape and were confronted outside the walls by the Mexican cavalry. After a room-to-room fight, Mexican soldiers gained control over the Alamo. Between five and seven Texians may have surrendered; if so, they were quickly executed on Santa Anna’s orders. Most eyewitness accounts reported between 182 and 257 Texian dead, while most Alamo historians agree that 400–600 Mexicans were killed or wounded. Women and children, primarily family members of the Texian soldiers, were questioned by Santa Anna and then released. On Santa Anna’s orders, three of the survivors were sent to Gonzales to spread word of the Texian defeat. The news sparked a panic known as the Runaway Scrape; the Texian army, most settlers, and the new Texas government fled east, away from the advancing army.

Within Mexico, the battle has often been overshadowed by events from the Mexican-American War in the 1840s. In 19th century Texas, the Alamo complex gradually became known as a battlesite rather than a former mission. The Texas Legislature purchased the buildings in the early part of the 20th century and designated the Alamo church building as an official Texas state shrine. It is now “the most popular tourist site in Texas”. The Alamo has been the subject of numerous non-fiction works, beginning in 1843. Most Americans, however, are more familiar with the myths spread by many of the film and television adaptations, including the 1955 miniseries Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier and John Wayne’s 1960 film The Alamo.

|

|

| New to this Website |

|

|

|

|

Index

Categories within 1st Recon Bn

Click the index for the Index page. |

| |

This website contains, in various sections, portions of copyrighted material not specifically authorized by the copyright owner. This material is used for educational purposes only and presented to provide understanding or give information for issues concerning the public as a whole. In accordance with U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. More Information

Information presented based on medical, news, government, and/or other web based articles or documents does not represent any medical recommendation or legal advice from myself or West Saint Paul Antiques. For specific information and advice on any condition or issue, you must consult a professional health care provider or legal advisor for direction.

I and West Saint Paul Antiques can not be responsible for information others may post on an external website linked here ~ or for websites which link to West Saint Paul Antiques. I would ask, however, that should you see something which you question or which seems incorrect or inappropriate, that you notify me immediately at floyd@weststpaulantiques.com Also, I would very much appreciate being notified if you find links which do not work or other problems with the website itself. Thank You!

Please know that there is no copyright infringement intended with any part of this website ~ should you find something that belongs to you and proper credit has not been given (or if you simply wish for me to remove it),

just let me know and I will do so right away.

|

Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

By using this website, West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, you are agreeing to use the site according to and in agreement with the above and following terms of use without limitation or qualification. If you do not agree, then you must refain from using the site.

The 'Terms of Use' govern your access to and use of this website and facebook pages associated with it. If you do not agree to all of the Terms of Use, do not access or use the website, or the facebook sites. By accessing or using any of them, you and any entity you are authorized to represent signify your agreement to be bound by the Terms of Use.

Said Terms of Use may be revised and/or updated at any time by posting of the changes on this page of the website. Your continued usage of the website, or the facebook site(s) after any changes to the Terms of Use will mean that you have accepted the changes. Also, any these sites themselves may be changed, supplemented, deleted, and/or updated at my sole discretion without notice; this establishes intellectual property rights by owner (myself).

It saddens me to include a Terms of Use for West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, but we all realize it is something that is necessary and must be done these days. By using the website, or facebook for West Saint Paul Antiques, you represent that you are of legal age and that you agree to be bound by the Terms of Use and any subsequent modifications. Your use of the West Saint Paul Antiques sites signify your electronic acceptance of the Terms of Use and constitute your signature to same as if you had actually signed an agreement embodying the terms.

|

|

| Thanks for stopping by... |

|

|

|