Important Message

This Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

Will be at the bottom of most web pages!

Please read it before using this website.

Thank You

|

North High School Class of 1966 Involvement in the Vietnam War.

|

|

| Previous Page |

|

|

|

|

| Next Page |

|

|

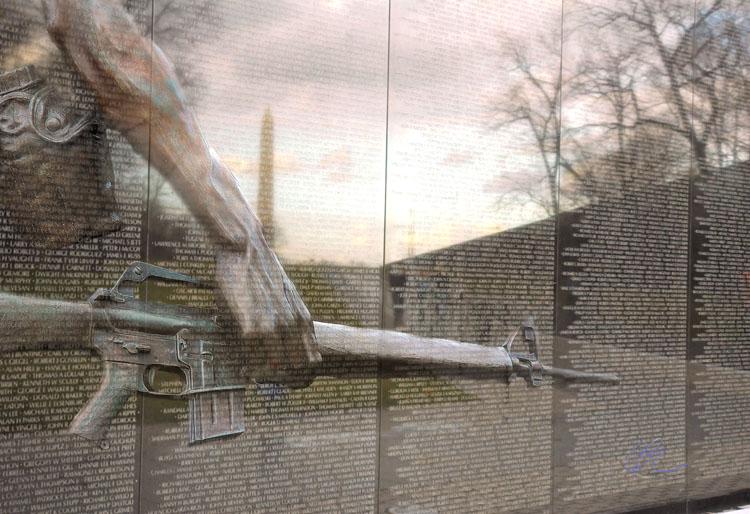

In Memory of

Classmates

|

Lost on the Vietnam Battlefield

|

|

Minneapolis North High School Class of '66

|

|

|

|

| Sergeant Richard Michael Hilt 1948-1969 |

|

|

|

| ***Lance Corporal Steven Howard Nelson*** 1947-1967 |

|

|

|

| ***Sergeant David Allan Weber*** 1947-1969 |

|

|

|

Click to Listen To The Music!

"Knockin' On Heaven Door "

|

|

| Click the photo for more Info. |

|

|

|

| Map of Fort Snelling National Cemetery - Click the photo... |

|

|

|

|

| Corporal Terry Rice |

|

| |

|

| Ky Ha, Viet Nam, 1967, 1st Provisional Rifle Co, USMC |

|

|

|

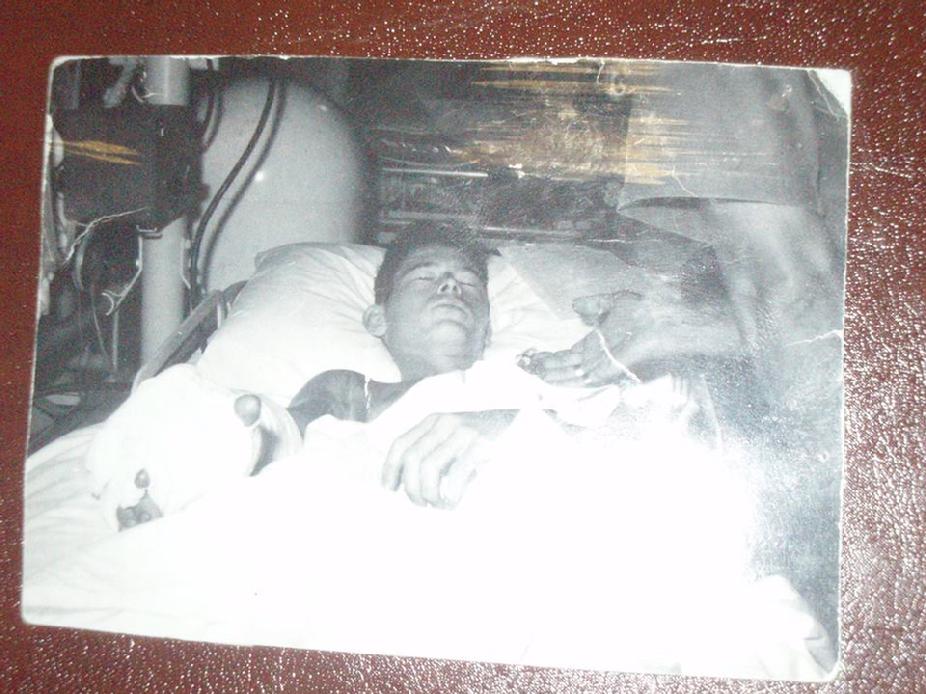

| Terry Rice - Purple Heart Ceremony Viet Nam |

|

|

| May 16th, 2016

Floyd Ruggles, her is a picture of my Purple Heart Ceremony, for the Viet Nam collage your are putting together for the Reunion.

Thanks Terry....

| |

|

|

| Corporal Terry Rice |

|

| |

|

| Photos of some of the gear Marines carried in Viet Nam |

|

|

|

| My friend Bill Jarmon and I, fall of 1966, before shipping out to Viet Nam. |

|

|

Terry Rice

Thank you for your service!

|

United States Air Force Master Sergeant Terry Rice

|

|

| Thank you for your service Terry |

|

|

|

|

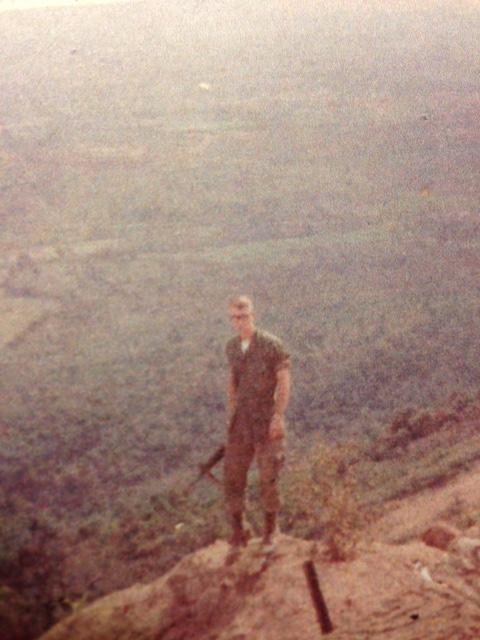

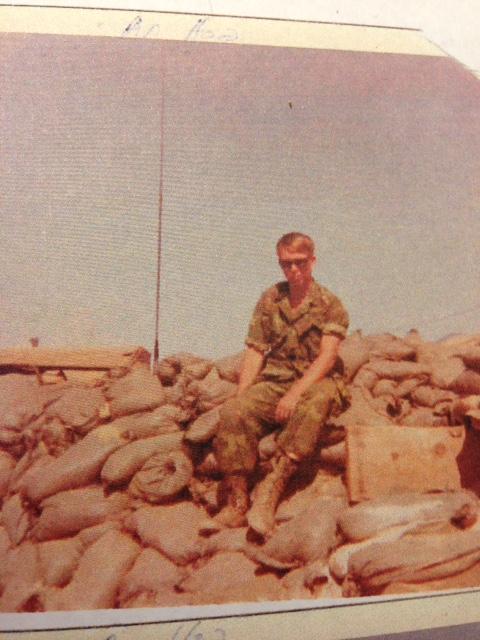

| Raymond W "Ray" Saatela |

|

| |

| I dug up some pictures I have from my tours in Vietnam.

I was en route to Vietnam in Sept '68 when I got temporarily assigned to a unit in Okinawa. I finally made it to Vietnam in Dec '68. I voluntarily extended my tour and after taking leave back home, I completed my extension and returned to the U.S. in April '70. I was a sergeant with communications and was always assigned to artillery batteries while in country. The locations of the photos are from around Danang, Chu Lai and An Hoa.

| |

|

Click to enlarge photos...

|

I was trained as a radio technician, but usually had little more than a screwdriver and a roll of tape to fix things while in the field. Therefore, I usually spent my days laying comm wire in the field, climbing poles to string it or being a radio operator.

I voluntarily extended my tour in Vietnam in order to qualify for an early-out program in effect at the time. My goal was to get out early enough to attend the fall quarter at the University of Minn. Unfortunately, after I completed my extended tour, my MOS was no longer on the list for eligible early outs. I finished out my marine corps enlistment in San Diego where five months later my MOS was again added to the eligibility list.

Ray Saatela

|

I wish I was still this thin.

|

|

|

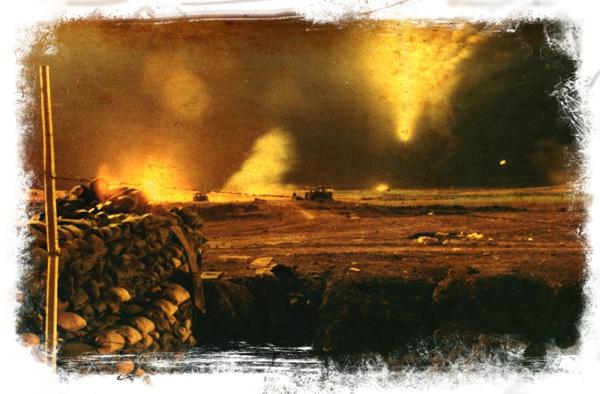

| Ray Saatela 1969 - An Hoa - Vietnam |

|

| |

An Hoa Combat Base

Vietnam

|

The base was located approximately 28 km west of Hội An and 4 km west northwest of the Mỹ Sơn temple complex, near to the Tinh Yen River and the An Hoa industrial complex.

The base was first used by the Marines in January 1966 during Operation Mallard when the 1st Battalion, 12th Marines established a firebase there while the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines and a Company from the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines swept the surrounding area. On 20 April 1966 the Marines returned to An Hoa on Operation Georgia, the 12th Marines reestablished a firebase while the 3rd Battalion 9th Marines provided security, the base would become permanent at this time as the Marines sought to pacify the area. On 6 July 5 Marine Battalions launched Operation Macon around the An Hoa area, the operation continued into October resulting in 24 Marines and 380Vietcong killed.

In August 1966 the Marines completed the construction of the "Liberty Road" between Danang and An Hoa.

An Hoa base was located southeast of a major Vietcong/People's Army of Vietnam base area known as the Arizona Territory across the Vu Gia River.

The airfield was capable of handling C-7, C-123 and C-130 aircraft.

Marine PFC Dan Bullock, the youngest American serviceman killed in action in the Vietnam War died at An Hoa on 7 June 1969.

The 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines handed over the base to the ARVN 1st Battalion, 51st Regiment on 15 October 1970.

|

|

| "Multi-Battalion Lift: Elements of the 5th Marine Regiment stand by at the An Hoa Base waiting to board Sea Knight helicopters of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 164 [HMM-164]. More than 3,500 Leatherneck infantrymen were airlifted November 20 in a sector about eight miles southwest of Da Nang as they kicked off Operation Meade River. Approximately 75 helicopters from three aircraft groups of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing [1st MAW] took part in the operation." |

|

|

History of An Hoa Combat Base

|

|

| An Hoa Combat Base - Art work based on a photo by Tim Elliott |

|

|

|

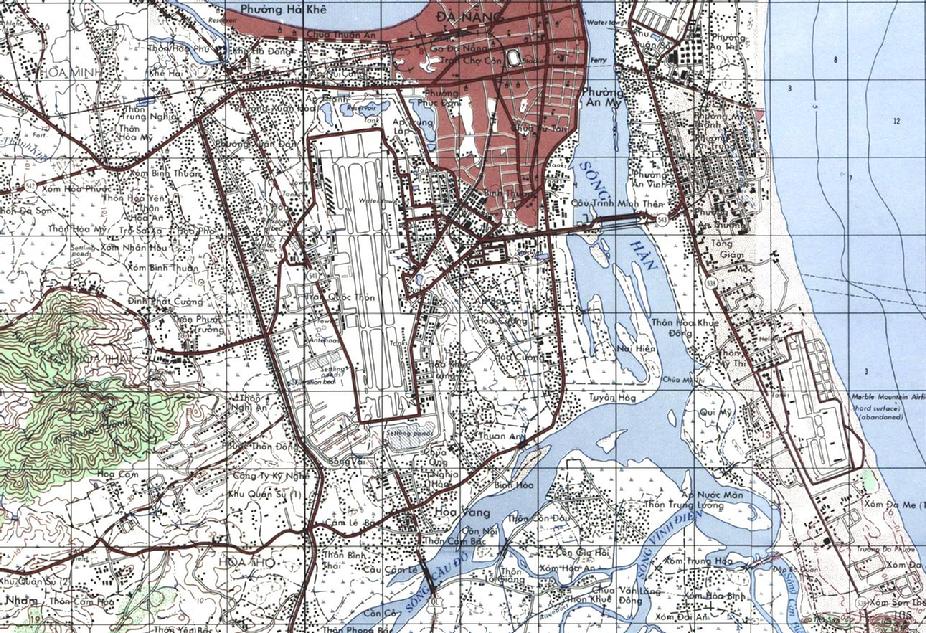

| In Danang, Where U.S. Troops First Landed, Members of the 9th U.S. Marine Expeditionary Force go ashore at Danang, South Vietnam, on March 8, 1965. Assigned to beef up defense of an air base, they were the first U.S. combat troops deployed in the Vietnam War. The first American combat troops to arrive in Vietnam landed in the coastal city of Danang 50 years ago this past March. The 2,000 Marines had the job of protecting the nearby U.S. air base. It took the members of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade almost an entire day to bring their men and materiel ashore that day in March 1965. |

|

|

The city of Da Nang mushroomed after the arrival of the first American combat troops on March 8, 1965. An advance guard of two battalions of Marines waded ashore at Red Beach in Da Nang Bay, providing the press with a photo opportunity that included amphibious landing craft, helicopters and young Vietnamese women handing out garlands – not quite as the generals had envisaged. The Marines had come to defend Da Nang’s massive US Air Force base; as the troops flew in so the base sprawled. Eventually Da Nang became “a small American city”, as journalist John Pilger remembers it, “with its own generators, water purification plants, hospitals, cinemas, bowling alleys, ball parks, tennis courts, jogging tracks, supermarkets and bars, lots of bars”. For most US troops the approach to Da Nang airfield formed their first impression of Vietnam, and it was here they came to take a break from the war at the famous China Beach.

At the same time the city swelled with thousands of refugees, mostly villagers cleared from “free-fire zones” but also people in search of work – labourers, cooks, laundry staff, pimps, prostitutes and drug pushers, all inhabiting a shantytown called Dogpatch on the base perimeter. Da Nang’s population rose inexorably: twenty thousand in the 1940s, fifty thousand in 1955 and, some estimate, a peak of one million during the American years. North Vietnamese mortar shells periodically fell in and around the base, but the city’s most violent scenes occurred when two South Vietnamese generals engaged in a little power struggle. In March 1966 Vice Air Marshal Ky, then prime minister of South Vietnam, ousted a popular Hué overlord, General Thi, following his open support of Buddhist dissidents. Demonstrations spread from Hué to Da Nang where troops loyal to Thi seized the airfield in what amounted to a mini civil war. After much posturing Ky crushed the revolt two months later, killing hundreds of rebel troops and many civilians. In the preceding chaos, the beleaguered rebels held forty Western journalists hostage for a brief period in Da Nang’s largest pagoda, Chua Tinh Hoi, while streets around filled with Buddhist protesters.

When the North Vietnamese Army finally arrived to liberate Da Nang on March 29, 1975, they had less of a struggle. Communist units had already cut the road south, and panic-stricken South Vietnamese soldiers battled for space on any plane or boat leaving the city, firing on unarmed civilians. Many drowned in the struggle to reach fishing boats, while planes and tanks were abandoned to the enemy. Da Nang had been all but deserted by South Vietnamese forces, leaving the mighty base to, according to Pilger, be “taken by a dozen NLF cadres waving white handkerchiefs from the back of a truck”.

|

|

| Danang East from Camp Horn to Marble Mtn Air Facility. |

|

|

|

| Da Nang Air Base |

|

| |

|

Click to enlarge photos...

|

|

| Da Nang Air Base |

|

|

|

| Thanks for your service Ray.... |

|

|

|

By Professor Robert K. Brigham, Vassar College

The Second Indochina War, 1954-1975, grew out of the long conflict between France and Vietnam. In July 1954, after one hundred years of colonial rule, a defeated France was forced to leave Vietnam. Nationalist forces under the direction of General Vo Nguyen Giap trounced the allied French troops at the remote mountain outpost of Dien Bien Phu in the northwest corner of Vietnam. This decisive battle convinced the French that they could no longer maintain their Indochinese colonies and Paris quickly sued for peace. As the two sides came together in Geneva, Switzerland, international events were already shaping the future of Vietnam's modern revolution.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Geneva Peace Accords

The Geneva Peace Accords, signed by France and Vietnam in the summer of 1954, reflected the strains of the international cold war. Drawn up in the shadow of the Korean War, the Geneva Accords represented the worst of all possible futures for war-torn Vietnam. Because of outside pressures brought to bear by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China, Vietnam's delegates to the Geneva Conference agreed to the temporary partition of their nation at the seventeenth parallel to allow France a face-saving defeat. The Communist superpowers feared that a provocative peace would anger the United States and its western European allies, and neither Moscow or Peking wanted to risk another confrontation with the West so soon after the Korean War. The Geneva Peace Accords, signed by France and Vietnam in the summer of 1954, reflected the strains of the international cold war. Drawn up in the shadow of the Korean War, the Geneva Accords represented the worst of all possible futures for war-torn Vietnam. Because of outside pressures brought to bear by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China, Vietnam's delegates to the Geneva Conference agreed to the temporary partition of their nation at the seventeenth parallel to allow France a face-saving defeat. The Communist superpowers feared that a provocative peace would anger the United States and its western European allies, and neither Moscow or Peking wanted to risk another confrontation with the West so soon after the Korean War.

According to the terms of the Geneva Accords, Vietnam would hold national elections in 1956 to reunify the country. The division at the seventeenth parallel, a temporary separation without cultural precedent, would vanish with the elections. The United States, however, had other ideas. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles did not support the Geneva Accords because he thought they granted too much power to the Communist Party of Vietnam.

Instead, Dulles and President Dwight D. Eisenhower supported the creation of a counter-revolutionary alternative south of the seventeenth parallel. The United States supported this effort at nation-building through a series of multilateral agreements that created the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).

South Vietnam Under Ngo Dinh Diem

Using SEATO for political cover, the Eisenhower administration helped create a new nation from dust in southern Vietnam. In 1955, with the help of massive amounts of American military, political, and economic aid, the Government of the Republic of Vietnam (GVN or South Vietnam) was born. The following year, Ngo Dinh Diem, a staunchly anti-Communist figure from the South, won a dubious election that made him president of the GVN. Almost immediately, Diem claimed that his newly created government was under attack from Communists in the north. Diem argued that the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV or North Vietnam) wanted to take South Vietnam by force. In late 1957, with American military aid, Diem began to counterattack. He used the help of the American Central Intelligence Agency to identify those who sought to bring his government down and arrested thousands. Diem passed a repressive series of acts known as Law 10/59 that made it legal to hold someone in jail if s/he was a suspected Communist without bringing formal charges.

The outcry against Diem's harsh and oppressive actions was immediate. Buddhist monks and nuns were joined by students, business people, intellectuals, and peasants in opposition to the corrupt rule of Ngo Dinh Diem. The more these forces attacked Diem's troops and secret police, the more Diem complained that the Communists were trying to take South Vietnam by force. This was, in Diem's words, "a hostile act of aggression by North Vietnam against peace-loving and democratic South Vietnam."

The Kennedy administration seemed split on how peaceful or democratic the Diem regime really was. Some Kennedy advisers believed Diem had not instituted enough social and economic reforms to remain a viable leader in the nation-building experiment. Others argued that Diem was the "best of a bad lot." As the White House met to decide the future of its Vietnam policy, a change in strategy took place at the highest levels of the Communist Party.

From 1956-1960, the Communist Party of Vietnam desired to reunify the country through political means alone. Accepting the Soviet Union's model of political struggle, the Communist Party tried unsuccessfully to cause Diem's collapse by exerting tremendous internal political pressure. After Diem's attacks on suspected Communists in the South, however, southern Communists convinced the Party to adopt more violent tactics to guarantee Diem's downfall. At the Fifteenth Party Plenum in January 1959, the Communist Party finally approved the use of revolutionary violence to overthrow Ngo Dinh Diem's government and liberate Vietnam south of the seventeenth parallel. In May 1959, and again in September 1960, the Party confirmed its use of revolutionary violence and the combination of the political and armed struggle movements. The result was the creation of a broad-based united front to help mobilize southerners in opposition to the GVN.

|

| Special Forces.

Photo courtesy of the soc.history.war. vietnam Home Page, from the Byrd Archives

|

|

The National Liberation Front

The united front had long and historic roots in Vietnam. Used earlier in the century to mobilize anti-French forces, the united front brought together Communists and non-Communists in an umbrella organization that had limited, but important goals. On December 20, 1960, the Party' s new united front, the National Liberation Front (NLF), was born. Anyone could join this front as long as they opposed Ngo Dinh Diem and wanted to unify Vietnam. The united front had long and historic roots in Vietnam. Used earlier in the century to mobilize anti-French forces, the united front brought together Communists and non-Communists in an umbrella organization that had limited, but important goals. On December 20, 1960, the Party' s new united front, the National Liberation Front (NLF), was born. Anyone could join this front as long as they opposed Ngo Dinh Diem and wanted to unify Vietnam.

The character of the NLF and its relationship to the Communists in Hanoi has caused considerable debate among scholars, anti-war activists, and policymakers. From the birth of the NLF, government officials in Washington claimed that Hanoi directed the NLF's violent attacks against the Saigon regime. In a series of government "White Papers," Washington insiders denounced the NLF, claiming that it was merely a puppet of Hanoi and that its non-Communist elements were Communist dupes. The NLF, on the other hand, argued that it was autonomous and independent of the Communists in Hanoi and that it was made up mostly of non-Communists. Many anti-war activists supported the NLF's claims. Washington continued to discredit the NLF, however, calling it the "Viet Cong," a derogatory and slang term meaning Vietnamese Communist.

December 1961 White Paper

In 1961, President Kennedy sent a team to Vietnam to report on conditions in the South and to assess future American aid requirements. The report, now known as the "December 1961 White Paper," argued for an increase in military, technical, and economic aid, and the introduction of large-scale American "advisers" to help stabilize the Diem regime and crush the NLF. As Kennedy weighed the merits of these recommendations, some of his other advisers urged the president to withdraw from Vietnam altogether, claiming that it was a "dead-end alley."

In typical Kennedy fashion, the president chose a middle route. Instead of a large-scale military buildup as the White Paper had called for or a negotiated settlement that some of his advisers had long advocated, Kennedy sought a limited accord with Diem. The United States would increase the level of its military involvement in South Vietnam through more machinery and advisers, but would not intervene whole-scale with troops. This arrangement was doomed from the start, and soon reports from Vietnam came in to Washington attesting to further NLF victories. To counteract the NLF's success in the countryside, Washington and Saigon launched an ambitious and deadly military effort in the rural areas. Called the Strategic Hamlet Program, the new counterinsurgency plan rounded up villagers and placed them in "safe hamlets" constructed by the GVN. The idea was to isolate the NLF from villagers, its base of support. This culturally-insensitive plan produced limited results and further alienated the peasants from the Saigon regime. Through much of Diem's reign, rural Vietnamese had viewed the GVN as a distant annoyance, but the Strategic Hamlet Program brought the GVN to the countryside. The Saigon regime's reactive policies ironically produced more cadres for the NLF.

|

| Marines holding up a captured National Liberation Front flag.

Photo courtesy of the soc.history.war. vietnam Home Page

|

|

Military Coup

By the summer of 1963, because of NLF successes and its own failures, it was clear that the GVN was on the verge of political collapse. Diem's brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, had raided the Buddhist pagodas of South Vietnam, claiming that they had harbored the Communists that were creating the political instability. The result was massive protests on the streets of Saigon that led Buddhist monks to self-immolation. The pictures of the monks engulfed in flames made world headlines and caused considerable consternation in Washington. By late September, the Buddhist protest had created such dislocation in the south that the Kennedy administration supported a coup. In 1963, some of Diem's own generals in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) approached the American Embassy in Saigon with plans to overthrow Diem. With Washington's tacit approval, on November 1, 1963, Diem and his brother were captured and later killed. Three weeks later, President Kennedy was assassinated on the streets of Dallas. By the summer of 1963, because of NLF successes and its own failures, it was clear that the GVN was on the verge of political collapse. Diem's brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, had raided the Buddhist pagodas of South Vietnam, claiming that they had harbored the Communists that were creating the political instability. The result was massive protests on the streets of Saigon that led Buddhist monks to self-immolation. The pictures of the monks engulfed in flames made world headlines and caused considerable consternation in Washington. By late September, the Buddhist protest had created such dislocation in the south that the Kennedy administration supported a coup. In 1963, some of Diem's own generals in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) approached the American Embassy in Saigon with plans to overthrow Diem. With Washington's tacit approval, on November 1, 1963, Diem and his brother were captured and later killed. Three weeks later, President Kennedy was assassinated on the streets of Dallas.

At the time of the Kennedy and Diem assassinations, there were 16,000 military advisers in Vietnam. The Kennedy administration had managed to run the war from Washington without the large-scale introduction of American combat troops. The continuing political problems in Saigon, however, convinced the new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, that more aggressive action was needed. Perhaps Johnson was more prone to military intervention or maybe events in Vietnam had forced the president's hand to more direct action. In any event, after a dubious DRV raid on two U.S. ships in the Gulf of Tonkin, the Johnson administration argued for expansive war powers for the president.

|

| Buddhist monks, 1969.

Photo courtesy of E. Kenneth Hoffman

|

|

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

In August 1964, in response to American and GVN espionage along its coast, the DRV launched a local and controlled attack against the C. Turner Joy and the U.S.S. Maddox, two American ships on call in the Gulf of Tonkin. The first of these attacks occurred on August 2, 1964. A second attack was supposed to have taken place on August 4, although Vo Nguyen Giap, the DRV's leading military figure at the time, and Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara have recently concluded that no second attack ever took place. In any event, the Johnson administration used the August 4 attack as political cover for a Congressional resolution that gave the president broad war powers. The resolution, now known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, passed both the House and Senate with only two dissenting votes (Senators Morse of Oregon and Gruening of Alaska). The Resolution was followed by limited reprisal air attacks against the DRV. In August 1964, in response to American and GVN espionage along its coast, the DRV launched a local and controlled attack against the C. Turner Joy and the U.S.S. Maddox, two American ships on call in the Gulf of Tonkin. The first of these attacks occurred on August 2, 1964. A second attack was supposed to have taken place on August 4, although Vo Nguyen Giap, the DRV's leading military figure at the time, and Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara have recently concluded that no second attack ever took place. In any event, the Johnson administration used the August 4 attack as political cover for a Congressional resolution that gave the president broad war powers. The resolution, now known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, passed both the House and Senate with only two dissenting votes (Senators Morse of Oregon and Gruening of Alaska). The Resolution was followed by limited reprisal air attacks against the DRV.

Throughout the fall and into the winter of 1964, the Johnson administration debated the correct strategy in Vietnam. The Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted to expand the air war over the DRV quickly to help stabilize the new Saigon regime. The civilians in the Pentagon wanted to apply gradual pressure to the Communist Party with limited and selective bombings. Only Undersecretary of State George Ball dissented, claiming that Johnson's Vietnam policy was too provocative for its limited expected results. In early 1965, the NLF attacked two U.S. army installations in South Vietnam, and as a result, Johnson ordered the sustained bombing missions over the DRV that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had long advocated.

The bombing missions, known as OPERATION ROLLING THUNDER, caused the Communist Party to reassess its own war strategy. From 1960 through late 1964, the Party believed it could win a military victory in the south "in a relatively short period of time." With the new American military commitment, confirmed in March 1965 when Johnson sent the first combat troops to Vietnam, the Party moved to a protracted war strategy. The idea was to get the United States bogged down in a war that it could not win militarily and create unfavorable conditions for political victory. The Communist Party believed that it would prevail in a protracted war because the United States had no clearly defined objectives, and therefore, the country would eventually tire of the war and demand a negotiated settlement. While some naive and simple-minded critics have claimed that the Communist Party, and Vietnamese in general, did not have the same regard for life and therefore were willing to sustain more losses in a protracted war, the Party understood that it had an ideological commitment to victory from large segments of the Vietnamese population.

|

| Battleship firing its main guns.

Photo courtesy of the soc.history.war. vietnam Home Page

|

|

The War in America

One of the greatest ironies in a war rich in ironies was that Washington had also moved toward a limited war in Vietnam. The Johnson administration wanted to fight this war in "cold blood." This meant that America would go to war in Vietnam with the precision of a surgeon with little noticeable impact on domestic culture. A limited war called for limited mobilization of resources, material and human, and caused little disruption in everyday life in America. Of course, these goals were never met. The Vietnam War did have a major impact on everyday life in America, and the Johnson administration was forced to consider domestic consequences of its decisions every day. Eventually, there simply were not enough volunteers to continue to fight a protracted war and the government instituted a draft. As the deaths mounted and Americans continued to leave for Southeast Asia, the Johnson administration was met with the full weight of American anti-war sentiments. Protests erupted on college campuses and in major cities at first, but by 1968 every corner of the country seemed to have felt the war's impact. Perhaps one of the most famous incidents in the anti-war movement was the police riot in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Hundreds of thousands ofcpeople came to Chicago in August 1968 to protest American intervention in Vietnam and the leaders of the Democratic Party who continued to prosecute the war. One of the greatest ironies in a war rich in ironies was that Washington had also moved toward a limited war in Vietnam. The Johnson administration wanted to fight this war in "cold blood." This meant that America would go to war in Vietnam with the precision of a surgeon with little noticeable impact on domestic culture. A limited war called for limited mobilization of resources, material and human, and caused little disruption in everyday life in America. Of course, these goals were never met. The Vietnam War did have a major impact on everyday life in America, and the Johnson administration was forced to consider domestic consequences of its decisions every day. Eventually, there simply were not enough volunteers to continue to fight a protracted war and the government instituted a draft. As the deaths mounted and Americans continued to leave for Southeast Asia, the Johnson administration was met with the full weight of American anti-war sentiments. Protests erupted on college campuses and in major cities at first, but by 1968 every corner of the country seemed to have felt the war's impact. Perhaps one of the most famous incidents in the anti-war movement was the police riot in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Hundreds of thousands ofcpeople came to Chicago in August 1968 to protest American intervention in Vietnam and the leaders of the Democratic Party who continued to prosecute the war.

The Tet Offensive

By 1968, things had gone from bad to worse for the Johnson administration. In late January, the DRV and the NLF launched coordinated attacks against the major southern cities. These attacks, known in the West as the Tet Offensive, were designed to force the Johnson administration to the bargaining table. The Communist Party correctly believed that the American people were growing war-weary and that its continued successes in the countryside had tipped the balance of forces in its favor. Although many historians have since claimed that the Tet Offensive was a military defeat, but a psychological victory for the Communists, it had produced the desired results. In late March 1968, a disgraced Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek the Democratic Party's re-nomination for president and hinted that he would go to the bargaining table with the Communists to end the war.

|

| Protest march in Washington D.C., early 1970s.

Photo courtesy of E. Kenneth Hoffman

|

|

The Nixon Years

The secret negotiations began in the spring of 1968 in Paris and soon it was made public that Americans and Vietnamese were meeting to discuss an end to the long and costly war. Despite the progress in Paris, the Democratic Party could not rescue the presidency from Republican challenger Richard Nixon who claimed he had a secret plan to end the war. The secret negotiations began in the spring of 1968 in Paris and soon it was made public that Americans and Vietnamese were meeting to discuss an end to the long and costly war. Despite the progress in Paris, the Democratic Party could not rescue the presidency from Republican challenger Richard Nixon who claimed he had a secret plan to end the war.

Nixon's secret plan, it turned out, was borrowing from a strategic move from Lyndon Johnson's last year in office. The new president continued a process called "Vietnamization", an awful term that implied that Vietnamese were not fighting and dying in the jungles of Southeast Asia. This strategy brought American troops home while increasing the air war over the DRV and relying more on the ARVN for ground attacks. The Nixon years also saw the expansion of the war into neighboring Laos and Cambodia, violating the international rights of these countries in secret campaigns, as the White House tried desperately to rout out Communist sanctuaries and supply routes. The intense bombing campaigns and intervention in Cambodia in late April 1970 sparked intense campus protests all across America. At Kent State in Ohio, four students were killed by National Guardsmen who were called out to preserve order on campus after days of anti-Nixon protest. Shock waves crossed the nation as students at Jackson State in Mississippi were also shot and killed for political reasons, prompting one mother to cry, "They are killing our babies in Vietnam and in our own backyard."

The expanded air war did not deter the Communist Party, however, and it continued to make hard demands in Paris. Nixon's Vietnamization plan temporarily quieted domestic critics, but his continued reliance on an expanded air war to provide cover for an American retreat angered U.S. citizens. By the early fall 1972, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and DRV representatives Xuan Thuy and Le Duc Tho had hammered out a preliminary peace draft. Washington and Hanoi assumed that its southern allies would naturally accept any agreement drawn up in Paris, but this was not to pass. The leaders in Saigon, especially President Nguyen van Thieu and Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, rejected the Kissinger-Tho peace draft, demanding that no concessions be made. The conflict intensified in December 1972, when the Nixon administration unleashed a series of deadly bombing raids against targets in the DRV's largest cities, Hanoi and Haiphong. These attacks, now known as the Christmas bombings, brought immediate condemnation from the international community and forced the Nixon administration to reconsider its tactics and negotiation strategy.

The Paris Peace Agreement

In early January 1973, the Nixon White House convinced the Thieu-Ky regime in Saigon that they would not abandon the GVN if they signed onto the peace accord. On January 23, therefore, the final draft was initialed, ending open hostilities between the United States and the DRV. The Paris Peace Agreement did not end the conflict in Vietnam, however, as the Thieu-Ky regime continued to battle Communist forces. From March 1973 until the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975, ARVN forces tried desperately to save the South from political and military collapse. The end finally came, however, as DRV tanks rolled south along National Highway One. On the morning of April 30, Communist forces captured the presidential palace in Saigon, ending the Second Indochina War.

|

|

1954

May 7, 1954

|

|

|

|

|

Vietnamese forces occupy the French command post at Dien Bien Phu and the French commander orders his troops to cease fire. The battle had lasted 55 days. Three thousand French troops were killed, 8,000 wounded. The Viet Minh suffered much worse, with 8,000 dead and 12,000 wounded, but the Vietnamese victory shattered France's resolve to carry on the war.

|

|

Vietnamese forces celebrate their victory over the French

|

|

|

1959

During 1959

|

|

|

|

|

A specialized North Vietnamese Army unit, Group 559, is formed to create a supply route from North Vietnam to Vietcong forces in South Vietnam. With the approval of Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia, Group 559 develops a primitive route along the Vietnamese/Cambodian border, with offshoots into Vietnam along its entire length. This eventually becomes known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

|

|

|

1961

Late 1961

|

|

|

|

|

President John F. Kennedy orders more help for the South Vietnamese government in its war against the Vietcong guerrillas. U.S. backing includes new equipment and more than 3,000 military advisors and support personnel.

|

|

President John F. Kennedy

|

|

|

December 11, 1961

|

|

|

|

|

American helicopters arrive at docks in South Vietnam along with 400 U.S. personnel, who will fly and maintain the aircraft.

|

|

|

1962

January 12, 1962

|

|

|

|

|

In Operation Chopper, helicopters flown by U.S. Army pilots ferry 1,000 South Vietnamese soldiers to sweep a NLF stronghold near Saigon. It marks America's first combat missions against the Vietcong.

|

|

U.S. Army helicopter on an Operation Chopper mission

|

|

|

Early 1962

|

|

|

|

|

Operation Ranchhand begins. The goal of Ranchhand is to clear vegetation alongside highways, making it more difficult for the Vietcong to conceal themselves for ambushes. As the war continues, the scope of Ranchhand increases. Vast tracts of forest are sprayed with "Agent Orange," an herbicide containing the deadly chemical Dioxin. Guerrilla trails and base areas are exposed, and crops that might feed Vietcong units are destroyed.

|

|

|

1963

January 2, 1963

|

|

|

|

|

At the hamlet of Ap Bac, the Vietcong 514th Battalion and local guerrilla forces ambush the South Vietnamese Army's 7th division. For the first time, the Vietcong stand their ground against American machinery and South Vietnamese soldiers. Almost 400 South Vietnamese are killed or wounded. Three American advisors are slain.

|

|

The victory at Ap Bac raised morale and drove recruitment for the Vietcong

|

|

|

1964

April - June 1964

|

|

|

|

|

American air power in Southeast Asia is massively reinforced. Two aircraft carriers arrive off the Vietnamese coast prompted by a North Vietnamese offensive in Laos.

|

|

|

July 30, 1964

|

|

|

|

|

On this night, South Vietnamese commandos attack two small North Vietnamese islands in the Gulf of Tonkin. The U.S. destroyer Maddox, an electronic spy ship, is 123 miles south with orders to electronically simulate an air attack to draw North Vietnamese boats away from the commandos.

|

|

|

August 4, 1964

|

|

|

|

|

The captain of the U.S.S. Maddox reports that his vessel has been fired on and that an attack is imminent. Though he later says that no attack took place, six hours after the initial report, a retaliation against North Vietnam is ordered by President Johnson. American jets bomb two naval bases, and destroy a major oil facility. Two U.S. planes are downed in the attack.

|

|

|

August 7, 1964

|

|

|

|

|

The U.S. congress passes the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, giving President Johnson the power to take whatever actions he sees necessary to defend southeast Asia.

|

|

President Johnson signs the Resolution

|

|

|

October 1964

|

|

|

|

|

China, North Vietnam's neighbor and ally, successfully tests an atomic bomb.

|

|

|

November 1, 1964

|

|

|

|

|

Two days before the U.S. presidential election, Vietcong mortars shell Bien Hoa Air Base near Saigon. Four Americans are killed, 76 wounded. Five B-57 bombers are destroyed, and 15 are damaged.

|

|

American aircraft burn on the ground at Bien Hoa

|

|

|

|

1965

January 1 - February 7, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

Vietcong forces mount a series of attacks across South Vietnam. They briefly seize control of Binh Gia, a village only 40 miles from Saigon. Two hundred South Vietnamese troops are killed near Binh Gia, along with five American advisors.

|

|

| The South Vietnamese lost 200 men at Binh Gia |

|

|

February 7, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

A U.S. helicopter base and advisory compound in the central highlands of South Vietnam is attacked by NLF commandos. Nine Americans are killed and more than 70 are wounded. President Johnson immediately orders U.S. Navy fighter-bombers to attack military targets just inside North Vietnam.

|

|

|

February 10, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

A Vietcong-placed bomb explodes in a hotel in Qui Nonh, killing 23 American servicemen.

|

|

| One of the American dead is carried to a waiting transport |

|

|

February 13, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

President Johnson authorizes Operation Rolling Thunder, a limited but long lasting bombing offensive. Its aim is to force North Vietnam to stop supporting Vietcong guerrillas in the South.

|

|

|

March 2, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

After a series of delays, the first bombing raids of Rolling Thunder are flown.

|

|

|

April 3, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

An American campaign against North Vietnam's transport system begins. In a month-long offensive, Navy and Air Force planes hit bridges, road and rail junctions, truck parks and supply depots.

|

|

|

April 7, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

The U.S. offers North Vietnam economic aid in exchange for peace, but the offer is summarily rejected. Two weeks later, President Johnson raises America's combat strength in Vietnam to more than 60,000 troops. Allied forces from Korea and Australia are added as a sign of international support.

|

|

|

May 11, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

Two and a half thousand Vietcong troops attack Song Be, a South Vietnamese provincial capital. After two days of fierce battles in and around the town, the Vietcong withdraw.

|

|

|

June 10, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

At Dong Xai, a South Vietnamese Army district headquarters and American Special Forces camp is overrun by a full Vietcong regiment. U.S. air attacks eventually drive the Vietcong away.

|

|

|

June 27, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

General William Westmoreland launches the first purely offensive operation by American ground forces in Vietnam, sweeping into NLF territory just northwest of Saigon.

|

|

|

|

August 17, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

After a deserter from the 1st Vietcong regiment reveals that an attack is imminent against the U.S. Marine base at Chu Lai, the American army launches Operation Starlite. In this, the first major battle of the Vietnam War, the United States scores a resounding victory. Ground forces, artillery from Chu Lai, ships and air support combine to kill nearly 700 Vietcong soldiers. U.S. forces sustain 45 dead and more than 200 wounded.

|

|

|

September - October 1965

|

|

|

|

|

After the North Vietnamese Army attacks a Special Forces camp at Plei Mei, the U.S. 1st Air Cavalry is deployed against enemy regiments that identified in the vicinity of the camp. The result is the battle of the Ia Drang. For 35 days, the division pursues and fights the 32d, 33d, and 66th North Vietnamese Regiments until the enemy, suffering heavy casualties, returns to bases in Cambodia.

|

|

|

November 17, 1965

|

|

|

|

|

Elements of the 66th North Vietnamese Regiment moving east toward Plei Mei encounter and ambush an American battalion. Neither reinforcements nor effective firepower can be brought in. When fighting ends that night, 60 percent of the Americans were casualties, and almost one of every three soldiers in the battalion had been killed.

|

|

|

1966

January 8, 1966

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. forces launch Operation Crimp. Deploying nearly 8,000 troops, it is the largest American operation of the war. The goal of the campaign is to capture the Vietcong's headquarters for the Saigon area, which is believed to be located in the district of Chu Chi. Though the area in Chu Chi is razed and repeatedly patrolled, American forces fail to locate any significant Vietcong base.

|

|

| American tanks and troops execute Operation Crimp |

|

|

February 1966

|

|

|

|

|

Hoping for head-on clashes with the enemy, U.S. forces launch four search and destroy missions in the month of February. Although there are two minor clashes with Vietcong regiments, there are no major conflicts.

|

|

|

March 5, 1966

|

|

|

|

|

The 272nd Regiment of the Vietcong 9th Division attack a battalion of the American 3rd Brigade at Lo Ke. U.S. air support succeeds in bombing the attackers into retreat. Two days later, the American 1st Brigade and a battalion of the 173rd Airborne are attacked by a Vietcong regiment, which is driven away by artillery fire.

|

|

|

April - May 1966

|

|

|

|

|

In Operation Birmingham, more than 5,000 U.S. troops, backed by huge numbers of helicopters and armored vehicles, sweep the area around north of Saigon. There are small scale actions between both armies, but over a three week period, only 100 Vietcong are killed. Most battles are dictated by the Vietcong, who prove elusive.

|

|

| Finding the Vietcong proves to be difficult |

|

|

Late May - June 1966

|

|

|

|

|

In late May 1966, the North Vietnamese 324B Division crosses the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and encounters a Marine battalion. The NVA holds their ground and the largest battle of the war to date breaks out near Dong Ha. Most of the 3rd Marine Division, some 5,000 men in five battalions, heads north. In Operation Hastings, the Marines backed by South Vietnamese Army troops, the heavy guns of U.S. warships and their artillery and air power drive the NVA back over the DMZ in three weeks.

|

|

|

June 30, 1966

|

|

|

|

|

On Route 13, which links Vietnam to the Cambodian border, American forces are brutally assaulted by the Vietcong. Only American air and artillery support prevents a complete disaster.

|

|

|

July 1966

|

|

|

|

|

Heavy fighting near Con Thien kills nearly 1,300 North Vietnamese troops.

|

|

|

October 1966

|

|

|

|

|

The Vietcong's 9th Division, having recovered from battles from the previous July, prepares for a new offensive. Losses in men and equipment have been replaced by supplies and reinforcements sent down the Ho Chi Minh trail from North Vietnam.

|

|

|

September 14, 1966

|

|

|

|

|

In a new mission code-named Operation Attleboro, the U.S. 196th Brigade and 22,000 South Vietnamese troops begin aggressive search and destroy sweeps through Tay Ninh Province. Almost immediately, huge caches of supplies belonging to the NLF 9th Division are discovered, but again, there is no head-to-head conflict. The mission ends after six weeks, with more than 1,000 Vietcong and 150 Americans killed.

|

|

| An American soldier examines a supply cache |

|

|

End of 1966

|

|

|

|

|

By the end of 1966, American forces in Vietnam reach 385,000 men, plus an additional 60,000 sailors stationed offshore. More than 6,000 Americans have been killed in this year, and 30,000 have been wounded. In comparison, an estimated 61,000 Vietcong have been killed. However, their troops now numbered over 280,000. |

|

US Marines vs Vietcong in Vietnam

"Contact (Ambush)" 1966 USMC

|

|

Click to enlarge photos...

|

Vietnam Peace War March, MLK Leads Procession April 18th, 1967

|

1967

January - May 1967

|

|

|

|

|

Two North Vietnamese divisions, operating out of the DMZ that separates North and South Vietnam, launch heavy bombardments of American bases south of the DMZ. These bases include Khe Sanh, the Rockpile, Cam Lo, Dong Ha, Con Thien and Gio Linh.

|

|

|

January 8, 1967

|

|

|

|

|

America forces begin Operation Cedar Falls, which is intended to drive Vietcong forces from the Iron Triangle, a 60 square mile area lying between the Saigon River and Route 13. Nearly 16,000 American troops and 14,000 soldiers of the South Vietnamese Army move into the Iron Triangle, but they encounter no major resistance. Huge quantities of enemy supplies are captured. Over 19 days, 72 Americans are killed, victims mostly of snipers emerging from concealed tunnels and booby traps. Seven hundred and twenty Vietcong are killed.

|

|

| Looking out from a patrol boat during Operation Cedar Falls |

|

|

February 21, 1967

|

|

|

|

|

In one of the largest air-mobile assaults ever, 240 helicopters sweep over Tay Ninh province, beginning Operation Junction City. The goal of Junction City is to destroy Vietcong bases and the Vietcong military headquarters for South Vietnam, all of which are located in War Zone C, north of Saigon. Some 30,000 U.S. troops take part in the mission, joined by 5,000 men of the South Vietnamese Army. After 72 days, Junction City ends. American forces succeed in capturing large quantities of stores, equipment and weapons, but there are no large, decisive battles.

|

|

| Junction City was one of the largest helicopter assaults ever staged |

|

|

April 24, 1967

|

|

|

|

|

American attacks on North Vietnam's airfields begin. The attacks inflict heavy damage on runways and installations. By the end of the year, all but one of the North's Mig bases has been hit.

|

|

|

May 1967

|

|

|

|

|

Desperate air battles rage in the skies over Hanoi and Haiphong. America air forces shoot down 26 North Vietnamese jets, decreasing the North's pilot strength by half.

|

|

|

Late May 1967

|

|

|

|

|

In the Central Highlands of South Vietnam, Americans intercept North Vietnamese Army units moving in from Cambodia. Nine days of continuous battles leave hundreds of North Vietnamese soldiers dead.

|

|

| Soldiers fighting in the central highlands |

|

|

Autumn 1967

|

|

|

|

|

In Hanoi, as Communist forces are building up for the Tet Offensive, 200 senior officials are arrested in a crackdown on opponents of the Tet strategy.

|

|

|

1968

Mid-January 1968

|

|

|

|

|

In mid-January 1968 in the remote northwest corner of South Vietnam, elements of three NVA divisions begin to mass near the Marine base at Khe Sanh. The ominous proportions of the build-up lead the U.S. commanders to expect a major offensive in the northern provinces.

|

|

|

January 21, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

At 5:30 a.m., a shattering barrage of shells, mortars and rockets slam into the Marine base at Khe Sanh. Eighteen Marines are killed instantly, 40 are wounded. The initial attack continues for two days.

|

|

|

|

January 30 - 31, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

On the Tet holiday, Vietcong units surge into action over the length and breadth of South Vietnam. In more than 100 cities and towns, shock attacks by Vietcong sapper-commandos are followed by wave after wave of supporting troops. By the end of the city battles, 37,000 Vietcong troops deployed for Tet have been killed. Many more had been wounded or captured, and the fighting had created more than a half million civilian refugees. Casualties included most of the Vietcong's best fighters, political officers and secret organizers; for the guerillas, Tet is nothing less than a catastrophe. But for the Americans, who lost 2,500 men, it is a serious blow to public support.

|

|

| Military police defend the US Embassy |

|

|

February 23, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

Over 1,300 artillery rounds hit the Marine base at Khe Sanh and its outposts, more than on any previous day of attacks. To withstand the constant assaults, bunkers at Khe Sanh are rebuilt to withstand 82mm mortar rounds.

|

|

|

March 6, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

While Marines wait for a massive assault, NVA forces retreat into the jungle around Khe Sanh. For the next three weeks, things are relatively quiet around the base.

|

|

|

March 11, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

Massive search and destroy sweeps are launched against Vietcong remnants around Saigon and other parts of South Vietnam.

|

|

|

March 16, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

In the hamlet of My Lai, U.S. Charlie Company kills about two hundred civilians. Although only one member of the division is tried and found guilty of war crimes, the repercussions of the atrocity is felt throughout the Army. However rare, such acts undid the benefit of countless hours of civic action by Army units and individual soldiers and raised unsettling questions about the conduct of the war.

|

|

|

March 22, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

Without warning, a massive North Vietnamese barrage slams into Khe Sanh. More than 1,000 rounds hit the base, at a rate of a hundred every hour. At the same time, electronic sensors around Khe Sanh indicate NVA troop movements. American forces reply with heavy bombing.

|

|

| Artillery slams into Khe Sanh |

|

|

April 8, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. forces in Operation Pegasus finally retake Route 9, ending the siege of Khe Sanh. A 77 day battle, Khe Sanh had been the biggest single battle of the Vietnam War to that point. The official assessment of the North Vietnamese Army dead is just over 1,600 killed, with two divisions all but annihilated. But thousands more were probably killed by American bombing.

|

|

|

June 1968

|

|

|

|

|

With strong, highly mobile American forces now in the area, and the base no longer needed for defense, General Westmoreland approves the abandonment and demolition of Khe Sanh.

|

|

|

November 1, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

After three-and-a-half years, Operation Rolling Thunder comes to an end. In total, the campaign had cost more than 900 American aircraft. Eight hundred and eighteen pilots are dead or missing, and hundreds are in captivity. Nearly 120 Vietnamese planes have been destroyed in air combat or accidents, or by friendly fire. According to U.S. estimates, 182,000 North Vietnamese civilians have been killed. Twenty thousand Chinese support personnel also have been casualties of the bombing. |

|

|

Click to enlarge photos...

|

1969

January 1969

|

|

|

|

|

President Richard M. Nixon takes office as the new President of the United States. With regard to Vietnam, he promises to achieve "Peace With Honor." His aim is to negotiate a settlement that will allow the half million U.S. troops in Vietnam to be withdrawn, while still allowing South Vietnam to survive.

|

|

| President Richard M. Nixon |

|

|

February 1969

|

|

|

|

|

In spite of government restrictions, President Nixon authorizes Operation Menu, the bombing of North Vietnamese and Vietcong bases within Cambodia. Over the following four years, U.S. forces will drop more than a half million tons of bombs on Cambodia.

|

|

|

February 22, 1969

|

|

|

|

|

In a major offensive, assault teams and artillery attack American bases all over South Vietnam, killing 1,140 Americans. At the same time, South Vietnamese towns and cities are also hit. The heaviest fighting is around Saigon, but fights rage all over South Vietnam. Eventually, American artillery and airpower overwhelm the Vietcong offensive.

|

|

| An American soldier leaps into a bunker during a Vietcong assault |

|

|

April 1969

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. combat deaths in Vietnam exceed the 33,629 men killed in the Korean War.

|

|

|

June 8, 1969

|

|

|

|

|

President Nixon meets with South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu on Midway Island in the Pacific, and announces that 25,000 U.S. troops will be withdrawn immediately.

|

|

|

1970

April 29, 1970

|

|

|

|

|

South Vietnamese troops attack into Cambodia, pushing toward Vietcong bases. Two days later, a U.S. force of 30,000 -- including three U.S. divisions -- mount a second attack. Operations in Cambodia last for 60 days, and uncover vast North Vietnamese jungle supply depots. They capture 28,500 weapons, as well as over 16 million rounds of small arms ammunition, and 14 million pounds of rice. Although most Vietcong manage to escape across the Mekong, there are over 10,000 casualties.

|

|

|

1971

February 8, 1971

|

|

|

|

|

In Operation Lam Son 719, three South Vietnamese divisions drive into Laos to attack two major enemy bases. Unknowingly, they are walking into a North Vietnamese trap. Over the next month, more than 9,000 South Vietnamese troops are killed or wounded. More than two thirds of the South Vietnamese Army's armored vehicles are destroyed, along with hundreds of U.S. helicopters and planes.

|

|

| A South Vietnamese soldier crouches behind a hill in Operation Lam Son 719 |

|

|

Summer 1971

|

|

|

|

|

While herbicides containing Dioxin were banned for use by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1968, spraying of Agent Orange continues in Vietnam until 1971. Operation Ranchhand has sprayed 11 million gallons of Agent Orange -- containing 240 pounds of the lethal chemical Dioxin -- on South Vietnam. More than one seventh of the country's total area has been laid waste.

|

|

|

1972

January 1, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

Only 133,000 U.S. servicemen remain in South Vietnam. Two thirds of America's troops have gone in two years. The ground war is now almost exclusively the responsibility of South Vietnam, which has over 1,000,000 men enlisted in its armed forces.

|

|

|

March 30, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

Massed North Vietnamese Army artillery open a shattering barrage, targeting South Vietnamese positions across the DMZ. Upwards of 20,000 NVA troops cross the DMZ, forcing the South Vietnamese units into a retreat. The Southern defense is thrown into complete chaos. Intelligence reports had predicted a Northern attack, but no one had expected it to come on the DMZ.

|

|

| South Vietnamese defend ineffectively against the North |

|

|

April 1, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

North Vietnamese soldiers push toward the city of Hue, which is defended by a South Vietnamese division and a division of U.S. Marines. But by April 9, the NVA are forced to halt attacks and resupply.

|

|

|

April 13, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

In an assault spearheaded by tanks, NVA troops manage to seize control of the northern part of the city. But the 4,000 South Vietnamese men defending the city, reinforced by elite airborne units, hold their positions and launch furious counterattacks. American B-52 bombers also help with the defense. A month later, Vietcong forces withdraw.

|

|

| Civilians flee from Hue in the face of the North Vietnamese's advance |

|

|

April 27, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

Two weeks after the initial attack, North Vietnamese forces again battle toward Quang Tri City. The defending South Vietnamese division retreats. By April 29, the NVA takes Dong Ha, and by May 1, Quang Tri City.

|

|

|

July 19, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

With U.S. air support, the South Vietnamese Army begins a drive to recapture Binh Dinh province and its cities. The battles last until September 15, by which time Quong Tri has been reduced to rubble. Nevertheless, the NVA retains control of the northern part of the province.

|

|

|

December 13, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

In Paris, peace talks between the North Vietnamese and the Americans breakdown.

|

|

|

|

December 18, 1972

|

|

|

|

|

By order of the president, a new bombing campaign starts against the North Vietnamese. Operation Linebacker Two lasts for 12 days, including a three day bombing period by up to 120 B-52s. Strategic surgical strikes are planned on fighter airfields, transport targets and supply depots in and around Hanoi and Haiphong. U.S. aircraft drop more than 20,000 tons of bombs in this operation. Twenty-six U.S. planes are lost, and 93 airmen are killed, captured or missing. North Vietnam admits to between 1,300 and 1,600 dead. |

|

1973

January 8, 1973

|

|

|

|

|

North Vietnam and the United States resume peace talks in Paris.

|

|

|

January 27, 1973

|

|

|

|

|

All warring parties in the Vietnam War sign a cease fire.

|

|

| Henry Kissenger's initials on the Cease Fire |

|

|

March 1973

|

|

|

|

|

The last American combat soldiers leave South Vietnam, though military advisors and Marines, who are protecting U.S. installations, remain. For the United States, the war is officially over. Of the more than 3 million Americans who have served in the war, almost 58,000 are dead, and over 1,000 are missing in action. Some 150,000 Americans were seriously wounded.

|

|

|

1974

January 1974

|

|

|

|

|

Though they are still too weak to launch a full-scale offensive, the North Vietnamese have rebuilt their divisions in the South, and have captured key areas.

|

|

| North Vietnamese resupply and fortify their forces |

|

|

August 9, 1974

|

|

|

|

|

President Richard M. Nixon resigns, leaving South Vietnam without its strongest advocate.

|

|

|

December 26, 1974

|

|

|

|

|

The 7th North Vietnamese Army division captures Dong Xoai.

|

|

|

1975

January 6, 1975

|

|

|

|

|

In a disastrous loss for the South Vietnamese, the NVA take Phuoc Long city and the surrounding province. The attack, a blatant violation of the Paris peace agreement, produces no retaliation from the United States.

|

|

| The North Vietnamese flag flies over Phouc Long |

|

|

March 1, 1975

|

|

|

|

|

A powerful NVA offensive is unleashed in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. The resulting South Vietnamese retreat is chaotic and costly, with nearly 60,000 troops dead or missing.

|

|

|

During March

|

|

|

|

|

Another NVA offensive sends 100,000 soldiers against the major cities of Quang Tri, Hue and Da Nang. Backed by powerful armored forces and eight full regiments of artillery, they quickly succeed in capturing Quang Tri province.

|

|

| North Vietnamese armored forces |

|

|

March 25, 1975

|

|

|

|

|

Hue, South Vietnam's third largest city, falls to the North Vietnamese Army.

|

|

|

Early April 1975

|

|

|

|

|

Five weeks into its campaign, the North Vietnamese Army has made stunning gains. Twelve provinces and more than eight million people are under its control. The South Vietnamese Army has lost its best units, over a third of its men, and almost half its weapons.

|

|

|

April 29, 1975

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. Marines and Air Force helicopters, flying from carriers off-shore, begin a massive airlift. In 18 hours, over 1,000 American civilians and almost 7,000 South Vietnamese refugees are flown out of Saigon.

|

|

| A helicopter lifts off from inside the U.S. Embassy grounds |

|

|

April 30, 1975

|

|

|

|

|

At 4:03 a.m., two U.S. Marines are killed in a rocket attack at Saigon's Tan Son Nhut airport. They are the last Americans to die in the Vietnam War. At dawn, the last Marines of the force guarding the U.S. embassy lift off. Only hours later, looters ransack the embassy, and North Vietnamese tanks role into Saigon, ending the war. In 15 years, nearly a million NVA and Vietcong troops and a quarter of a million South Vietnamese soldiers have died. Hundreds of thousands of civilians had been killed. |

|

North Vietnamese and Viet Cong Military deaths

According to the Vietnamese government, there were 1,100,000 North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong military personnel deaths during theVietnam War (including the missing). Rummel reviewed the many casualty data sets, and this number is in keeping with his mid-level estimate of 1,011,000 North Vietnamese combatant deaths. The official US Department of Defense figure was 950,765 communist forces killed in Vietnam from 1965 to 1974. Defense Department officials believed that these body count figures need to be deflated by 30 percent. In addition, Guenter Lewy assumes that one-third of the reported "enemy" killed may have been civilians, concluding that the actual number of deaths of communist military forces was probably closer to 444,000.

|

|

| Previous Page |

|

| |

|

| Next Page |

|

|

| A Soldier's Prayer

(author unknown)

Do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning's hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.

| |

| Thanks for Stopping By...

| |

|

| Thanks for stopping by today |

|

|

This website contains, in various sections, portions of copyrighted material not specifically authorized by the copyright owner. This material is used for educational purposes only and presented to provide understanding or give information for issues concerning the public as a whole. In accordance with U.S. Copyright Law Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. More Information

Information presented based on medical, news, government, and/or other web based articles or documents does not represent any medical recommendation or legal advice from myself or West Saint Paul Antiques. For specific information and advice on any condition or issue, you must consult a professional health care provider or legal advisor for direction.

I and West Saint Paul Antiques can not be responsible for information others may post on an external website linked here ~ or for websites which link to West Saint Paul Antiques. I would ask, however, that should you see something which you question or which seems incorrect or inappropriate, that you notify me immediately at floyd@weststpaulantiques.com Also, I would very much appreciate being notified if you find links which do not work or other problems with the website itself. Thank You!

Please know that there is no copyright infringement intended with any part of this website ~ should you find something that belongs to you and proper credit has not been given (or if you simply wish for me to remove it),

just let me know and I will do so right away.

|

Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

By using this website, West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, you are agreeing to use the site according to and in agreement with the above and following terms of use without limitation or qualification. If you do not agree, then you must refain from using the site.

The 'Terms of Use' govern your access to and use of this website and facebook pages associated with it. If you do not agree to all of the Terms of Use, do not access or use the website, or the facebook sites. By accessing or using any of them, you and any entity you are authorized to represent signify your agreement to be bound by the Terms of Use.

Said Terms of Use may be revised and/or updated at any time by posting of the changes on this page of the website. Your continued usage of the website, or the facebook site(s) after any changes to the Terms of Use will mean that you have accepted the changes. Also, any these sites themselves may be changed, supplemented, deleted, and/or updated at my sole discretion without notice; this establishes intellectual property rights by owner (myself).

It saddens me to include a Terms of Use for West Saint Paul Antiques . Com, but we all realize it is something that is necessary and must be done these days. By using the website, or facebook for West Saint Paul Antiques, you represent that you are of legal age and that you agree to be bound by the Terms of Use and any subsequent modifications. Your use of the West Saint Paul Antiques sites signify your electronic acceptance of the Terms of Use and constitute your signature to same as if you had actually signed an agreement embodying the terms.

|

|