Poetry Coffee Cup Cafe

Poet of the Year (2010)

Emily Emily Dickinson Dickinson

|

| Poetry Coffee Cup Cafe's Favorite Poet of the year: Emily Dickinson |

|

|

My Favorite Poet

by Michael Ryan |

|

|

There is no information in Emily Dickinson's poems that separates her from us. She works the seams of language through her mastery of rhetoric and poetic form. She extracts from words "amazing sense." Instead of merely referring to the experience of the writer, the poem is made to be an experience for the reader, which is precisely how she says she knows poetry in her famous remark to Higginson: "If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way"

No, there isn't. Dickinson is the only poet about whom I consistently feel, "I wish I could write like that." My ambition to understand her inside out is to absorb all she can give me, but her rigorous attention to paradox and its manifold exfoliations are beyond me. The inimitable stylistic manifestation of this attention is most apparent in her usage not her vocabulary—condensing predications and changing grammatical classes of words much more than using specialized and obscure meanings of them (although there is a little of that, too). To cite just one example: "The Daily Own - of Love/ Depreciate the Vision" (426)—as Cristanne Miller says in A Poet's Grammar—"creates a kind of parataxis, for which the reader must work out the appropriate relationship." A verb ("Own") is the subject of a sentence that also violates rules of subject-verb agreement ("The Own…Depreciate"). Dickinson makes the reader participate in the poem, to follow its twists and fill in its (sometimes unfillable) blanks. Her style is in the service of truth: truth-telling and truth-discovering: "Truth is such a rare thing it is delightful to tell it" (as Higginson reported she said to him). She jolts us with it. And she jolted herself. The knocked-off top of her head must have spent a good deal of time on the floor next to her desk. The occasional difficulty and irresolvable ambiguity of her poems is incidental to their knocking my head off, too. That difficulty is more in what is being said than in how it's being said. She is never more difficult than she has to be, but she is committed to being exactly that difficult (and that easy), and her figuration and condensation are sometimes necessarily dense and usually unusually intense.

So the so-called "enigma of Emily Dickinson" is not an enigma to me at all. Everything we need to know about her is in those 1789 poems. They are a spiritual autobiography more comprehensive than any possible narrative. They are both the product and practice of a lifetime act of love on her part, if love can be a necessary action ("My business is to love," she declared. "My business is to sing."). Definition poems, observation-of-nature poems, arresting-moment-dramatized poems, declaration-after-experience poems, working-what-she-thinks-of-the-experience-in-the-poem poems, lyric cries, locked-up aphorisms, arguments and narratives, purposeful inconsistency, jazzing the placeholders, banging and angling language until it renders the otherwise inarticulate human feeling: the variety of the poetry she extracts from a single limited form—a liturgical form (the hymn stanza)—is astonishing. I would like to have a fraction of her focus: the most intense focus ever of any writer I know. She is a model of devotion to the practice of poetry. Writing poems for her was life-sustaining, even life-creating. It created the place in which she fully experienced her experience. What she made in her poems she used in her life. The process of writing and all it involved grew her soul. It was a spiritual discipline, the lifelong practice of a craft, and an entertainment. When after a few years out of touch, Higginson asked if she was still writing, she responded, "I have no other Playmate." The idea that either poetry or religion was separable from life was repugnant to her. Art for art's sake would have struck her as a ludicrous, debased idea. The foundation and purpose of art was moral and religious, as it was for every poet of her time except Poe, but, unlike the Victorian sages, for her the relationship between art and morality was implicit not explicit, private not social, neither pious nor privileged but enmeshed with gritty, difficult, daily life, and every crack and crease in their connections was open to exploration. I am very grateful she did this work. It is one of the greatest enrichments of my life.

|

|

| Poetry Coffee Cup Cafe's Favorite Poems |

| Wild Nights – Wild Nights! |

|

| by Emily Dickinson |

|

|

Wild Nights – Wild Nights!

Were I with thee

Wild Nights should be

Our luxury!

Futile – the winds –

To a heart in port –

Done with the compass –

Done with the chart!

Rowing in Eden –

Ah, the sea!

Might I moor – Tonight –

In thee!

|

|

| Two Butterflies went out at Noon— |

|

| by Emily Dickinson |

|

Two Butterflies went out at Noon—

And waltzed above a Farm—

Then stepped straight through the

Firmament And rested on a Beam—

And then—together bore away

Upon a shining Sea—

Though never yet, in any Port—

Their coming mentioned—be—

If spoken by the distant Bird—

If met in Ether Sea

By Frigate, or by Merchantman—

No notice—was—to me— |

|

| It's all I have to bring today |

|

| by Emily Dickinson |

|

|

It's all I have to bring today –

This, and my heart beside –

This, and my heart, and all the fields –

And all the meadows wide –

Be sure you count – should I forget

Some one the sum could tell –

This, and my heart, and all the Bees

Which in the Clover dwell.

|

|

Emily Dickinson

1830-1886

We outgrow love like other things

And put it in the drawer,

Till it an antique fashion shows

Like costumes grandsires wore.

Who has not found the heaven below

Will fail of it above.

God's residence is next to mine,

His furniture is love.

Because I could not stop for Death,

He kindly stopped for me;

The carriage held but just ourselves

And Immortality.

We slowly drove, he knew no haste,

And I had put away

My labor, and my leisure too,

For his civility.

We passed the school where children played,

Their lessons scarcely done;

We passed the fields of gazing grain,

We passed the setting sun.

We paused before a house that seemed

A swelling of the ground;

The roof was scarcely visible,

The cornice but a mound.

Since then 'tis centuries; but each

Feels shorter than the day

I first surmised the horses' heads

Were toward eternity.

After great pain, a formal feeling comes

The nerves sit ceremonious, like tombs

The stiff heart questions was it he, that bore,

And yesterday, or centuries before?

The feet, mechanical, go round

Of ground, or air, or ought

A wooden way

Regardless grown,

A quartz contentment, like a stone.

This is the hour of lead

Remembered, if outlived,

As freezing persons recollect the snow.

First chill - then stupor - then the letting go.

Pain has an element of blank;

It cannot recollect

When it began, or if there were

A day when it was not.

It has no future but itself,

Its infinite realms contain

Its past, enlightened to perceive

New periods of pain.

How many schemes may die

In one short Afternoon

Entirely unknown

To those they most concern -

The man that was not lost

Because by accident

He varied by a Ribbon's width

From his accustomed route -

The Love that would not try

Because beside the Door

It must be competitions

Some unsuspecting Horse was tied

Surveying his Despair.

|

Publication

Despite Dickinson's prolific writing, fewer than a dozen of her poems were published during her lifetime. After her younger sister Vinnie discovered the collection of nearly eighteen hundred poems, Dickinson's first volume was published four years after her death. Until the 1955 publication of Dickinson's Complete Poems by Thomas H. Johnson, her poetry was considerably edited and altered from their manuscript versions. Since 1890 Dickinson has remained continuously in print.

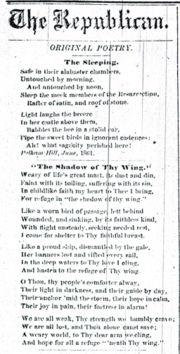

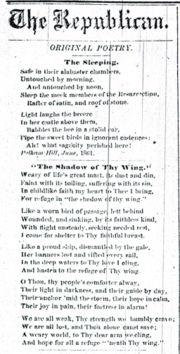

A few of Dickinson's poems appeared in Samuel Bowles' Springfield Republican between 1858 and 1868. They were published anonymously and heavily edited, with conventionalized punctuation and formal titles. The first poem, "Nobody knows this little rose", may have been published without Dickinson's permission. The Republican also published "A narrow Fellow in the Grass" as "The Snake"; "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –" as "The Sleeping"; and "Blazing in the Gold and quenching in Purple" as "Sunset". The poem "I taste a liquor never brewed –" is an example of the edited versions, the last two lines in the first stanza were completely rewritten for the sake of conventional rhyme.

-

|

Original wording

I taste a liquor never brewed –

From Tankards scooped in Pearl –

Not all the Frankfort Berries

Yield such an Alcohol!

|

Republican version

I taste a liquor never brewed –

From Tankards scooped in Pearl –

Not Frankfort Berries yield the sense

Such a delirious whirl!

|

|

In 1864, several poems were altered and published in Drum Beat, to raise funds for medical care for Union soldiers in the war. Another appeared in April 1864 in the Brooklyn Daily Union.

In the 1870s, Higginson showed Dickinson's poems to Helen Hunt Jackson, who had coincidentally been at the Academy with Dickinson when they were girls. Jackson was deeply involved in the publishing world, and managed to convince Dickinson to publish her poem "Success is counted sweetest" anonymously in a volume called A Masque of Poets. The poem, however, was altered to agree with contemporary taste. It was the last poem published during Dickinson's lifetime.

Posthumous

After Dickinson's death, Vinnie Dickinson kept her promise and burned most of the poet's correspondence. Significantly though, Dickinson had left no instructions about the forty notebooks and loose sheets gathered in a locked chest. Vinnie recognized the poems' worth and became obsessed with seeing them published. She turned first to her brother's wife and then to Mabel Loomis Todd, her brother's mistress, for assistance. A feud ensued, with the manuscripts divided between the Todd and Dickinson houses, preventing complete publication of Dickinson's poetry for more than half a century.

|

Contemporary Structure and syntax Reception

|

|

| Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –," entitled "The Sleeping," as it was published in the Springfield Republican in 1862. |

|

|

|

| Dickinson's handwritten manuscript of her poem "Wild Nights – Wild Nights!" |

|

|

|

| Dickinson wrote and sent this poem ("A Route to Evanescence") to Thomas Higginson in 1880. |

|

|

Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, in 1830. She attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, but severe homesickness led her to return home after one year. Throughout her life, she seldom left her house and visitors were scarce. The people with whom she did come in contact, however, had an enormous impact on her thoughts and poetry. She was particularly stirred by the Reverend Charles Wadsworth, whom she met on a trip to Philadelphia. He left for the West Coast shortly after a visit to her home in 1860, and some critics believe his departure gave rise to the heartsick flow of verse from Dickinson in the years that followed. While it is certain that he was an important figure in her life, it is not certain that this was in the capacity of romantic love—she called him "my closest earthly friend." Other possibilities for the unrequited love in Dickinson’s poems include Otis P. Lord, a Massachusetts Supreme Court Judge, and Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield Republican.

By the 1860s, Dickinson lived in almost total physical isolation from the outside world, but actively maintained many correspondences and read widely. She spent a great deal of this time with her family. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was actively involved in state and national politics, serving in Congress for one term. Her brother Austin attended law school and became an attorney, but lived next door once he married Susan Gilbert (one of the speculated—albeit less persuasively—unrequited loves of Emily). Dickinson’s younger sister Lavinia also lived at home for her entire life in similar isolation. Lavinia and Austin were not only family, but intellectual companions during Dickinson’s lifetime.

Dickinson's poetry reflects her loneliness and the speakers of her poems generally live in a state of want, but her poems are also marked by the intimate recollection of inspirational moments which are decidedly life-giving and suggest the possibility of happiness. Her work was heavily influenced by the Metaphysical poets of seventeenth-century England, as well as her reading of the Book of Revelation and her upbringing in a Puritan New England town which encouraged a Calvinist, orthodox, and conservative approach to Christianity.

She admired the poetry of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, as well as John Keats. Though she was dissuaded from reading the verse of her contemporary Walt Whitman by rumor of its disgracefulness, the two poets are now connected by the distinguished place they hold as the founders of a uniquely American poetic voice. While Dickinson was extremely prolific as a poet and regularly enclosed poems in letters to friends, she was not publicly recognized during her lifetime. The first volume of her work was published posthumously in 1890 and the last in 1955. She died in Amherst in 1886.

Upon her death, Dickinson's family discovered 40 handbound volumes of nearly 1800 of her poems, or "fascicles" as they are sometimes called. These booklets were made by folding and sewing five or six sheets of stationery paper and copying what seem to be final versions of poems in an order that many critics believe to be more than chronological. The handwritten poems show a variety of dash-like marks of various sizes and directions (some are even vertical). The poems were initially unbound and published according to the aesthetics of her many early editors, removing her unusual and varied dashes and replacing them with traditional punctuation. The current standard version replaces her dashes with a standard "n-dash," which is a closer typographical approximation of her writing. Furthermore, the original order of the works was not restored until 1981, when Ralph W. Franklin used the physical evidence of the paper itself to restore her order, relying on smudge marks, needle punctures and other clues to reassemble the packets. Since then, many critics have argued for thematic unity in these small collections, believing the ordering of the poems to be more than chronological or convenient. The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson (Belknap Press, 1981) remains the only volume that keeps the order intact.

A Selected Bibliography

Poetry

Bolts of Melody: New Poems of Emily Dickinson (1945)

Final Harvest: Emily Dickinson's Poems (1962)

Further Poems of Emily Dickinson: Withheld from Publication by Her Sister Lavinia (1929)

Poems by Emily Dickinson (1890)

Poems: Second Series (1891)

Poems: Third Series (1896)

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (1924)

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (1960)

The Single Hound: Poems of a Lifetime (1914)

Unpublished Poems of Emily Dickinson (1935)

Prose

Emily Dickinson Face to Face: Unpublished Letters with Notes and Reminisces (1932)

Letters of Emily Dickinson (1894)

|

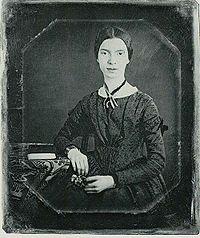

| Emily Dickinson - Photo Gallery |

|

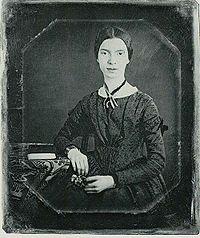

| A drawing of the young Emily Dickinson, age nine. It was made from a portrait featuring Emily, Austin and Lavinia as children. |

|

|

|

| Photo courtesy of Amherst College Library |

|

|

|

| From the daguerreotype taken at Mount Holyoke, December 1846 or early 1847. It is the only authenticated portrait of Emily Dickinson later than childhood. |

|

|

|

| The Dickinson Homestead as it appears today. In 2003 it was made into the Emily Dickinson Museum. |

|

|

|

| Supposedly one of only two known daguerreotypes of Emily Dickinson. Made in the 1850s and discovered in 2000. |

|

|

|

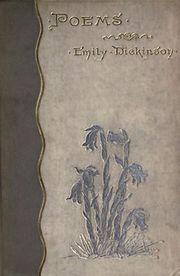

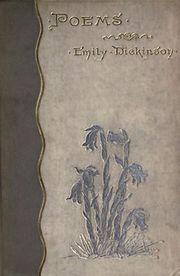

| Cover of the first edition of Poems, published in 1890 |

|

|

|

They shut me up in Prose –

As when a little Girl

They put me in the Closet –

Because they liked me "still" –

Still! Could themself have peeped –

And seen my Brain – go round –

They might as wise have lodged a Bird

For Treason – in the Pound –

|

| Emily Dickinson, c. 1862 |

|

|

| Emily Dickinson's tombstone in the family plot. |

|

|

|

A solemn thing – it was – I said –

A Woman – White – to be –

And wear – if God should count me fit –

Her blameless mystery –

|

| Emily Dickinson, c. 1861 |

|

| An Introduction to Emily Dickinson |

Emily Dickinson had only one literary critic during her lifetime: T. H. Higginson, an editor at the Atlantic Monthly. After he wrote a piece encouraging new writers, Dickinson sent him a small selection of poems, knowing from his past writings that he was particularly sympathetic to the cause of female writers. He ultimately became her only critic and literary mentor. In their first correspondence, she asked him if her poems were "alive" and if they "breathed." He called her a "wholly new and original poetic genius." He then immediately advised her against publication. Most likely, Higginson felt that she was unclassifiable within the poetic establishment of the day—departing from traditional forms as well as conventions of language and meter, her poems would have seemed odd, even unacceptable, to her contemporary audience. Even though he failed her as a critic and colleague—telling her not to publish, never offering any real encouragement—she was pleased that he read her poems, and credited her audience of one with "saving her life."

Dickinson’s subject matter is best understood in how it reflects but also departs from her background and education. It is unclear to biographers and critics exactly what books Dickinson had access to, beyond the books that she makes mention of, often cryptically, in her letters. Among the 100 or so classic works found in her family library (some of which may not have been in the library during her lifetime) and a few hundred more mundane works and popular novels that she discussed in letters, it is unlikely that she had read more than a handful of philosophers, poets, and novelists. Influenced most by the Bible, Shakespeare, and the seventeenth century metaphysicals (noted for their extravagant metaphors in linking disparate objects), she wrote poems on grief, love, death, loss, affection and longing. Her presumed reading in the natural sciences, also reconstructed from studying her family library, allowed her to bring precision and individuality to natural subjects, observing nature for itself, rather than as a testament to the glory of creation, and touching upon the less beautiful aspects of nature, such as weeds and clover. Her forms were various and included riddles, declarations, complaints, love songs, stories, arguments, prayers, and definitions.

Drawing from primarily musical forms such as hymns and ballads, and modifying them with her own sense of rhythm and sound, a Dickinson poem is unusual in that it both slows down and speeds up, interrupts itself, holds its breath, and sometimes trails off. The reader is led through the poem by the shape of her stanza forms, typically quatrains, and her unusual emphasis of words, either through capitalization or line position. The meter varies quite a bit even from the stresses expected in a hymn or ballad. Hymn meter differs from traditional meter by counting syllables, not "feet." Unlike ballad meter, quatrains are typically closed, meaning that the first and third lines will rhyme as well as the second and fourth. Some common forms of hymn meter that Dickinson used are common meter (a line of eight syllables followed by a line of six syllables, repeating in quatrains of an 8/6/8/6 pattern), long meter (8/8/8/8), short meter (6/6/6/6), and common particular meter (8/8/6/8/8/6). However, unlike writers of traditional hymns, Dickinson took liberties with the meter. She also allowed herself to use enjambment more frequently than traditional hymn writers, breaking a line where there is no natural or syntactic pause. For example, in the second stanza of "I cannot live with you," she writes:

The Sexton keeps the Key to –

Putting up

Our Life – His Porcelain –

Like a Cup –

Dickinson breaks the first line after a preposition and before a direct object; in both places, one would not traditionally punctuate with a comma, semicolon, or dash, and there would be no pause.

Since so few of her poems were published during her lifetime, the posthumous discovery of Dickinson’s cache of poems presented an unusual variety of challenges. What is now known as her poetics or prosody is bound to a discussion of how her poems have been edited, and how her handwritten manuscripts have been interpreted in contemporary editions.

Beyond deciphering her handwriting and trying to guess at dates, editors have had to work from poems that often appeared in several unfinished forms, with no clear, definitive version. Early publications of her selected poems were horribly botched in an attempt to "clean up" her verse; they were only restored in the collected poems as edited by Thomas H. Johnson in 1955, first in three volumes with considerable variants for each poem, and then in a single volume of all 1755 poems five years later in which a "best copy" was chosen for each poem. In no case were several versions of a poem combined. Only twenty-five were given titles by Johnson, and those often reluctantly. The titling system used most frequently today is the numbers assigned by Thomas H. Johnson in his various collected editions, along with the first line of the poem.

A typical manuscript for a poem might include several undated versions, with varying capitalization throughout, sometimes a "C" or an "S" that seems to be somewhere between lowercase and capital, and no degree of logic in the capitalization. While important subject words and the symbols that correspond to them are often capitalized, often (but not always) a metrically stressed word will be capitalized as well, even if it has little or no relevance in comparison to the rest of the words in the poem. Early editors removed all capitals but the first of the line, or tried to apply editorial logic to their usage. For example, poem 632 is now commonly punctuated as follows:

The Brain – is wider than the Sky –

For – put them side by side –

The one the other will contain

With ease – and You – beside –

The Brain is deeper than the sea –

For – hold them – Blue to Blue –

The one the other will absorb –

As Sponges – Buckets – do –

The Brain is just the weight of God –

For – Heft them – Pound for Pound –

And they will differ – if they do –

As Syllable from Sound –

The above capitalizations, which include such seemingly unimportant words as "Blue," "Sponges," and "Buckets," capitalizing "Sky" but not "sea," were regularized into the following traditional capitalization and punctuation by early editors:

The brain is wider than the sky,

For, put them side by side,

The one the other will include

With ease, and you beside.

The brain is deeper than the sea,

For, hold them, blue to blue,

The one the other will absorb,

As sponges, buckets do.

The brain is just the weight of God,

For, lift them, pound for pound,

And they will differ, if they do,

As syllable from sound.

The punctuation is equally difficult to decipher; what is now known as Dickinson’s characteristic "dash" is actually a richer variety of pen markings that have no typographical correspondents. Dashes are either long or short; sometimes vertical, as if to indicate musical phrasing, and often elongated periods, as if to indicate a slightly different kind of pause. Poem 327, "Before I got my eye put out," the original manuscript of which can be found online, ends with one of these markings:

So safer – guess – with just my soul

Upon the Window pane –

Where other Creatures put their eyes –

Incautious – of the Sun –

In keeping with her background in church hymns, some modern critics have even discussed the upwards or downwards movement of a dash, as if it might correspond to a "lifting" or "falling" phrase. Dickinson uses dashes musically, but also to create a sense of the indefinite, a different kind of pause, an interruption of thought, to set off a list, as a semi-colon, as parentheses, or to link two thoughts together—the shape of any individual dash might be seen as joining two thoughts together or pushing them apart. One of the most characteristic uses of the dash is at the end of a poem with a closed rhyme; the meter would shut, like a door, but the punctuation seems open. In these cases, it is likely meant to serve as an elongated end-stop. The dash was historically an informal mark, used in letters and diaries but not academic writing, and removing the dashes changes, even upon first glance, the visual liveliness and vigor of her verses. While Johnson’s system of transcribing all dash-like markings as a printed "n-dash," or short dash (as above), is imperfect, in early editions, these dashes were replaced by more regularized punctuation, such as commas and periods. Poem 320, "We play at Paste," was changed in punctuation, capitalization, and even stanza form.

We play at Paste –

Till qualified, for Pearl –

Then, drop the Paste –

And deem ourself a fool –

The Shapes – though – were similar –

And our new Hands

Learned Gem-Tactics –

Practicing Sands –

The above poem, when published for the first time, looked like this:

We play at paste,

Till qualified for pearl,

Then drop the paste,

And deem ourself a fool.

The shapes, though, were similar,

And our new hands

Learned gem-tactics

Practicing sands.

Not only does the poem leave a completely different visual impression on the page, but the pacing created by the punctuation is distorted as well, causing "The Shapes – though – were similar –" to be compressed into "The shapes, though, were similar." Finally, a traditional period ends the poem with more certainty than the original would suggest.

While altering capitalization or punctuation seems like a horrible offense to these poems, other editorial gestures were even more egregious. In an effort to make Dickinson’s poems seem more educated, words were replaced. What is now known as "the heft/ Of cathedral tunes" (from 258) was altered, with no textual variant, to "weight" by Dickinson’s first editor, Mabel Todd. Other changes included fixing misspellings, which seems innocuous enough, but sometimes involved removing a New England pronunciation that she might have been trying to indicate, as well as more serious swapping of lines and regularizing of her most unusual rhythms and meters. The selected poems were arranged in no particular order; one great challenge of Dickinson scholarship has been reassembling her hand-bound packets, or fascicles, as they are sometimes called, to reflect the order that she may have intended. They were originally taken apart and deemed useless, or merely chronological. As is typical with most poets, the most frequently anthologized poems have not often reflected the breadth of Dickinson's political range, erotic sensibilities, theological challenges, or depth of darkness. Her poems were cleaned up not only in mechanics, but also in subject matter.

The critical reaction to Dickinson’s poems did not occur during her lifetime, as only seven poems were published, and those anonymously. Since she was "discovered," critical and popular reaction has historically trailed the various publishing strategies for her work. Once seen as religious, bland, even sentimental, she is increasingly becoming understood for her strangeness and versatility, especially after the publication of Johnson’s 1955 edition, and most recently, facsimiles of the manuscripts. The myth, or perhaps exaggeration, of her reclusiveness (recent scholarship has shown that at least an element of it was quite normal for an unmarried woman devoted to her family), and the tendency of biographers to attach her poems to a mysterious unrequited love, have obscured more serious scholarship for too long as critics have overlayed a fantasy of her life onto her poems. Unsurprisingly, she has benefited greatly from feminist scholarship, most notably in the biography by Alfred Habegger. She is now regarded as one of the two founders of American poetics, alongside Walt Whitman, but her legacy provides an alternate direction for American verse—her abstract, spare musicality and contemplative introversion providing a counterpoint to Whitman’s sprawling lines, concrete subject matter, and grandiosity.

Reading Dickinson requires that we tune our ear to her peculiarity, and look, as she did, into the "look of death," observe "a certain slant of light," and perhaps "play at paste"—consider ourselves to be, as she considered herself, "of barefoot rank" until we are transformed by this strange apprenticeship. Click for top of this page Emily Dickinson's page

|

| The Poet - Emily Dickinson's - Life Store |

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born at the Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts on December 10, 1830 into a prominent, but not opulent, family. Two hundred years earlier, the Dickinsons had arrived in the New World—in the puritan Great Migration—where they prospered. Emily Dickinson's paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, had almost single-handedly founded Amherst College. In 1813, he built the Homestead, the large mansion on the town's Main Street that became the focus of Dickinson family life for the better part of a century. Samuel Dickinson's eldest son, Eward, was treasurer of Amherst College for nearly forty years, served numerous terms as a State Legislator, and represented the Hampshire district in the United States Congress. On May 6, 1828, he married Emily Norcross from Monson. They had three children:

- William Austin (1829–1895), known as Austin, Aust or Awe;

- Emily Elizabeth and;

- Lavinia Norcross (1833–1899), known as Lavinia or Vinnie.

By all accounts, young Emily was a well-behaved girl. On an extended visit to Monson when she was two, Emily's Aunt Lavinia described Emily as "perfectly well & contented—She is a very good child & but little trouble."Emily's aunt also noted the girl's affinity for music and her particular talent for the piano, which she called "the moosic".

Dickinson attended primary school in a two-story building on Pleasant Street. Her education was "ambitiously classical for a Victorian girl". Her father wanted his children well-educated and he followed their progress even while away on business. When Emily was seven, he wrote home reminding his children to "keep school, and learn, so as to tell me, when I come home, how many new things you have learned". While Emily consistently described her father in a warm manner, her correspondence suggests that her mother was regularly cold and aloof. In a letter to a confidante, Emily wrote she "always ran Home to Awe [Austin] when a child, if anything befell me. He was an awful Mother, but I liked him better than none."

On September 7, 1840, Dickinson and her sister Vinnie started together at Amherst Academy, a former boys' school that had opened to female students just two years earlier. At about the same time, her father purchased a house on North Pleasant Street. Emily's brother Austin later described this large new home as the "mansion" over which he and Emily presided as "lord and lady" while their parents were absent. The house overlooked Amherst's burial ground, described by one local minister as treeless and "forbidding

|

|

Teenage years

Dickinson spent seven years at the Academy, taking classes in English and

classical literature, Latin, botany, geology, history, "mental philosophy" and

arithmetic. She had a few terms off due to illness: the longest absence was in 1845–1846 when she was only enrolled for eleven weeks.

Dickinson was troubled from a young age by the "deepening menace" of death, especially the deaths of those who were close to her. When Sophia Holland, her second cousin and a close friend, grew ill from typhus and died in April 1844, Emily was traumatized. Recalling the incident two years later, Emily wrote that "it seemed to me I should die too if I could not be permitted to watch over her or even look at her face." She became so melancholic that her parents sent her to stay with family in Boston to recover. With her health and spirits restored, she soon returned to Amherst Academy to continue her studies. During this period, she first met people who were to become lifelong friends and correspondents, such as Abiah Root, Abby Wood, Jane Humphrey and Susan Huntington Gilbert (who later married Emily's brother Austin).

In 1845, a religious revival took place in Amherst, resulting in 46 confessions of faith among Dickinson's peers. Dickinson wrote to a friend the following year: "I never enjoyed such perfect peace and happiness as the short time in which I felt I had found my savior." She went on to say that it was her "greatest pleasure to commune alone with the great God & to feel that he would listen to my prayers". The experience did not last: Dickinson never made a formal declaration of faith and attended services regularly for only a few years. After her church-going ended, about 1852, she wrote a poem opening: "Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – / I keep it, staying at Home".

During the last year of her stay at the Academy, Emily became friendly with Leonard Humphrey, its popular new young principal. After finishing her final term at the Academy on August 10, 1847, Dickinson began attending Mary Lyon's Mount Holyoke Frmale

Seminary (which later became Mount Holyoke College) in South Hadley, about ten miles (16 km) from Amherst. She was at the Seminary for only ten months. Although she liked the girls at Holyoke, Dickinson made no lasting friendships there. The explanations for her brief stay at Holyoke differ considerably: either she was in poor health, her father wanted to have her at home, she rebelled against the evangelical fervor present at the school, she disliked the discipline-minded teachers, or she was simply homesick. Whatever the specific reason for leaving Holyoke, her brother Austin appeared on March 25, 1848 to "bring [her] home at all events". Back in Amherst, Dickinson occupied her time with household activities. She took up baking for the family and enjoyed attending local events and activities in the budding college town.

Early influences and writing

When she was eighteen, Dickinson's family befriended a young attorney by the name of Benjamin Franklin Newton. According to a letter written by Dickinson after Newton's death, he had been "with my Father two years, before going to Worcester – in pursuing his studies, and was much in our family." Although their relationship was probably not romantic, Newton was a formative influence and would become the second in a series of older men (after Humphrey) that Dickinson referred to variously as her tutor, preceptor or master.

Newton likely introduced her to the writings of William Wordsworth, and his gift to her of Ralph Waldo Emerson's first book of collected poems had a liberating effect. She wrote later that he, "whose name my Father's Law Student taught me, has touched the secret Spring". Newton held her in high regard, believing in and recognizing her as a poet. When he was dying of tuberculosis, he wrote to her, saying that he would like to live until she achieved the greatness he foresaw. Biographers believe that Dickinson's statement of 1862—"When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality – but venturing too near, himself – he never returned"—refers to Newton.

Dickinson was familiar not only with the Bible but also with contemporary popular literature. Dickinson was probably influenced by

Lydia Maria Child's Letters from New York, another gift from Newton (after reading it, she enthused "This then is a book! And there are more of them!"). Her brother smuggled a copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Kavanagh into the house for her (because her father might disapprove) and a friend lent her Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre in late 1849. Jane Eyre's influence cannot be measured, but when Dickinson acquired her first and only dog, a Newfoundland, she named him Carlo after the character St. John Rivers' dog. William Shakespeare was a potent influence in her life. Referring to his plays, she wrote to one friend "Why clasp any hand but this?" and to another "Why is any other book needed?"

Adulthood and seclusion

In early 1850 Dickinson wrote that "Amherst is alive with fun this winter ... Oh, a very great town this is!" Her high spirits soon turned to melancholy after another untimely death. The Amherst Academy principal, Leonard Humphrey, died suddenly of "brain congestion" at age 25. Two years after his death, she revealed to her friend Abiah Root the extent of her depression: "... some of my friends are gone, and some of my friends are sleeping – sleeping the churchyard sleep – the hour of evening is sad – it was once my study hour – my master has gone to rest, and the open leaf of the book, and the scholar at school alone, make the tears come, and I cannot brush them away; I would not if I could, for they are the only tribute I can pay the departed Humphrey".

During the 1850s, Emily's strongest and most affectionate relationship was with Susan Gilbert. Emily eventually sent her over three hundred letters, more than to any other correspondent, over the course of their friendship. Her missives typically dealt with demands for Sue's affection and the fear of unrequited admiration, but because Sue was often aloof and disagreeable, Emily was continually hurt by what was mostly a tempestuous friendship. Sue was nevertheless supportive of the poet, playing the role of "most beloved friend, influence, muse, and adviser whose editorial suggestions Dickinson sometimes followed, Susan played a primary role in Emily's creative processes." Sue married Austin in 1856 after a four-year courtship, although their marriage was not a happy one. Edward Dickinson built a house for him and Sue called the Evergreens, which stood on the west side of the Homestead.

Until 1855, Dickinson had not strayed far from Amherst. That spring, accompanied by her mother and sister, she took one of her longest and farthest trips away from home. First, they spent three weeks in Washington, where her father was representing

Massachusetts in Congress. Then they went to Philadelphia for two weeks to visit family. In Philadelphia, she met Charles Wadsworth, a famous minister of the Arch Street Presbyterian Church, with whom she forged a strong friendship which lasted until his death in 1882. Despite only seeing him twice after 1855 (he moved to San Francisco in 1862), she variously referred to him as "my Philadelphia", "my Clergyman", "my dearest earthly friend" and "my Shepherd from 'Little Girl'hood".

From the mid-1850s, Emily's mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses until her death in 1882. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Emily said that she would visit if she could leave "home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her". As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson's domestic responsibilities weighed heavier upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Vinnie stated that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Emily took this role as her own, and "finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it".

Withdrawing more and more from the outside world, Emily began in the summer of 1858 what would be her lasting legacy. Reviewing poems she had written previously, she began making clean copies of her work, assembling carefully pieced-together manuscript books. The forty fascicles she created from 1858 through 1865 eventually held nearly eight hundred poems. No one was aware of the existence of these books until after her death.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner and editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican, and his wife, Mary. They visited the Dickinsons regularly for years to come. During this time Emily sent him over three dozen letters and nearly fifty poems. Their friendship brought out some of her most intense writing and Bowles published a few of her poems in his journal. It was from 1858 to 1861 that Dickinson is believed to have written a trio of letters that have been called "The Master Letters". These three letters, drafted to an unknown man simply referred to as "Master", continue to be the subject of speculation and contention amongst scholars.

The first half of the 1860s, after she had largely withdrawn from social life, proved to be Dickinson's most productive writing period.

Is "my Verse ... alive?"

In April 1862, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a literary critic, radical adolitionist and ex-minister, wrote a lead piece for The Atlantic

Monthly entitled "Letter to a Young Contributor". Higginson's essay, in which he urged aspiring writers to "Charge your style with life", contained practical advice for those wishing to break into print. Seeking literary guidance that no one close to her could provide, Dickinson sent him a letter which read in full:

Mr Higginson,

Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?

The Mind is so near itself – it cannot see, distinctly – and I have none to ask –

Should you think it breathed – and had you the leisure to tell me, I should feel quick gratitude –

If I make the mistake – that you dared to tell me – would give me sincerer honor – toward you –

I enclose my name – asking you, if you please – Sir – to tell me what is true?

That you will not betray me – it is needless to ask – since Honor is it's [sic] own pawn –

The letter was unsigned, but she had included her name on a card and enclosed it in an envelope along with four of her poems. He praised her work but suggested that she delay publishing until she had written longer, being unaware that she had already appeared in print. She assured him that publishing was as foreign to her "as Firmament to Fin" but also proposed that "If fame belonged to me, I could not escape her".

Dickinson delighted in dramatic self-characterization and mystery in her letters to Higginson. She said of herself: "I am small, like the wren, and my hair is bold, like the chestnut bur, and my eyes like the sherry in the glass that the guest leaves." She stressed her solitary nature, stating that her only real companions were the hills, the sundown and her dog, Carlo. She also mentioned that whereas her mother did not "care for Thought", her father bought her books, but begged her "not to read them – because he fears they joggle the Mind". Dickinson valued his advice, going from calling him "Mr. Higginson" to "Dear friend" as well as signing her letters "Your Gnome" and "Your Scholar". His interest in her work certainly provided great moral support; many years later, Dickinson told Higginson that he had saved her life in 1862. They corresponded until her death.

The woman in white

In direct opposition to the immense productivity that she displayed in the early 1860s, Dickinson wrote fewer poems in 1866. Beset with personal loss as well as loss of domestic help, it is possible that Dickinson was too overcome to keep up her previous level of writing. Carlo died during this time after sixteen years of companionship; Dickinson never owned another dog. Although the household servant of nine years had married and left the Homestead that same year, it was not until 1869 that her family brought in a permanent household servant to replace the old one. Emily once again was responsible for chores, including the baking, at which she excelled.

Around this time, Dickinson's behavior began to change. She did not leave the Homestead unless it was absolutely necessary and as early as 1867, she began to talk to visitors from the other side of a door rather than speaking to them face to face. She acquired local notoriety; she was rarely seen and when she was, she was usually clothed in white. Dickinson's one surviving article of clothing is a white cotton dress, possibly sewn circa 1878–1882. Few of the locals who exchanged messages with Dickinson during her last fifteen years ever saw her in person. Austin and his family began to protect Emily's privacy, deciding that she was not to be a subject of discussion with outsiders. Despite her physical seclusion, however, Dickinson was socially active and expressive through what makes up two-thirds of her surviving notes and letters. When visitors came to either the Homestead or the Evergreens, she would often leave or send over small gifts of poems or flowers. Dickinson also had a good rapport with the children in her life. Mattie Dickinson, the second child of Austin and Sue, later said that "Aunt Emily stood for indulgence." MacGregor (Mac) Jenkins, the son of family friends who later wrote a short article in 1891 called "A Child's Recollection of Emily Dickinson", thought of her as always offering support to the neighborhood children.

When Higginson urged her to come to Boston in 1868 so that they could formally meet for the first time, she declined, writing: "Could it please your convenience to come so far as Amherst I should be very glad, but I do not cross my Father's ground to any House or town". It was not until he came to Amherst in 1870 that they met. Later he referred to her, in the most detailed and vivid physical account of her on record, as "a little plain woman with two smooth bands of reddish hair ... in a very plain & exquisitely clean white pique & a blue net worsted shawl." He also felt that he never was "with any one who drained my nerve power so much. Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her."

Posies and poesie

Scholar Judith Farr notes that Dickinson, during her lifetime, "was known more widely as a gardener, perhaps, than as a poet". Dickinson studied botany from the age of nine and, along with her sister, tended the garden at Homestead. During her lifetime, she assembled a collection of pressed plants in a sixty-six page leather-bound herbarium. It contained 424 pressed flower specimens that she collected, classified and labeled using the Linnaean system. The Homestead garden was well-known and admired locally in its time. It has not survived and Dickinson kept no garden notebooks or plant lists, but a clear impression can be formed from the letters and recollections of friends and family. Her niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, remembered "carpets of lily-of-the-valley and

pansies, platoons of sweetpeas, hyacinths enough in May to give all the bees of summer dyspepsia. There were ribbons of peony hedges and drifts of daffodils in season, marigolds to distraction—a butterfly utopia". In particular, Dickinson cultivated scented exotic flowers, writing that she "could inhabit the Spice Isles merely by crossing the dining room to the conservatory, where the plants hang in baskets". Dickinson would often send her friends bunches of flowers with verses attached, but "they valued the posy more than the poetry".

Later life

On June 16, 1874, while in Boston, Edward Dickinson suffered a stroke and died. When the simple funeral was held in the Homestead's entrance hall, Emily stayed in her room with the door cracked open. Neither did she attend the memorial service on June 28. She wrote to Higginson that her father's "Heart was pure and terrible and I think no other like it exists." A year later, on June 15, 1875, Emily's mother also suffered a stroke, which produced a partial lateral paralysis and impaired memory. Lamenting her mother's increasing physical as well as mental demands, Emily wrote that "Home is so far from Home".

Otis Phillips Lord, an elderly judge on the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court

from Salem, in 1872 or 1873, became an acquaintance of Dickinson's. After the death of Lord's wife in 1877, his friendship with Dickinson probably became a late-life romance, though as their letters were destroyed, this is surmise. Dickinson found a kindred soul in Lord, especially in terms of shared literary interests; the few letters which survived contain multiple quotations of Shakepeare's work, including the plays Othello, Antony and Cleapatra, Hamlet and King Lear. In 1880 he gave her Cowden Clarke's Complete Concordance to Shakespeare (1877). Dickinson wrote that "While others go to Church, I go to mine, for are you not my Church, and have we not a Hymn that no one knows but us?" She referred to him as "My lovely Salem" and they wrote to each other religiously every Sunday. Dickinson looked forward to this day greatly; a surviving fragment of a letter written by her states that "Tuesday is a deeply depressed Day".

After being critically ill for several years, Judge Lord died in March 1884. Dickinson referred to him as "our latest Lost" Two years before this, on April 1, 1882, Dickinson's "Shepherd from 'Little Girl'hood", Charles Wadsworth, also died after a long illness.

Decline and death

Although she continued to write in her last years, Dickinson stopped editing and organizing her poems. She also exacted a promise from her sister Lavinia to burn her papers. Lavinia, who also never married, remained at the Homestead until her own death in 1899.

The 1880s were a difficult time for the remaining Dickinsons. Irreconcilably alienated from his wife, Austin fell in love in 1882 with

Mabel Loomis Todd, an Amherst College faculty wife who had recently moved to the area. Todd never met Dickinson but was intrigued by her, referring to her as "a lady whom the people call the Myth". Austin distanced himself from his family as his affair continued and his wife became sick with grief. Dickinson's mother died on November 14, 1882. Five weeks later, Dickinson wrote "We were never intimate ... while she was our Mother – but Mines in the same Ground meet by tunneling and when she became our Child, the Affection came." The next year, Austin and Sue's third and youngest child, Gilbert—Emily's favorite—died of typhoid fever.

As death succeeded death, Dickinson found her world upended. In the fall of 1884, she wrote that "The Dyings have been too deep for me, and before I could raise my Heart from one, another has come." That summer she had seen "a great darkness coming" and fainted while baking in the kitchen. She remained unconscious late into the night and weeks of ill health followed. On November 30, 1885, her feebleness and other symptoms were so worrying that Austin canceled a trip to Boston. She was confined to her bed for a few months, but managed to send a final burst of letters in the spring. What is thought to be her last letter was sent to her cousins, Louise and Frances Norcross, and simply read: "Little Cousins, Called Back. Emily". On May 15, 1886, after several days of worsening symptoms, Emily Dickinson died at the age of 55. Austin wrote in his diary that "the day was awful ... she ceased to breathe that terrible breathing just before the [afternoon] whistle sounded for six." Dickinson's chief physician gave the cause of death as Bright's disease and its duration as two and a half years.

Dickinson was buried, laid in a white coffin with vanilla-scented heliotrope, a Lady's Slipper orchild and a "knot of blue field violets" placed about it. The funeral service, held in the Homestead's library, was simple and short; Higginson, who had only met her twice, read "No Coward Soul Is Mine", a poem by Emily Bronte that had been a favorite of Dickinson's. At Dickinson's request, her "coffin [was] not driven but carried through fields of buttercups" for burial in the family plot at West Cemetery on Triangle Street.

The first volume of Dickinson's Poems, edited jointly by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, appeared in November 1890. Although Todd claimed that only essential changes were made, the poems were extensively edited to match punctuation and capitalization to late 19th-century standards, with occasional rewordings to reduce Dickinson's obliquity. The first 115-poem volume was a critical and financial success, going through eleven printings in two years. Poems: Second Series followed in 1891, running to five editions by 1893; a third series appeared in 1896. One reviewer, in 1892, wrote: "The world will not rest satisfied till every scrap of her writings, letters as well as literature, has been published". Two years later, two volumes of Dickinson's letters, heavily edited, appeared. In parallel, Susan Dickinson placed a few of Dickinson's poems in literary magazines such as Scribner's Magazine and The Independent.

Between 1914 and 1929, Dickinson's niece, Martha Dickinson Bianchi, published a new series of collections, including many previously unpublished poems, with similarly normalized punctuation and capitalization. Other volumes edited by Todd and Bianchi followed through the 1930s, gradually making more previously unpublished poems available.

The first scholarly publication came in 1955 with a complete new three-volume set edited by Thomas H. Johnson. It formed the basis of all later Dickinson scholarship. For the first time, the poems were printed very nearly as Dickinson had left them in her manuscripts. They were untitled, only numbered in an approximate chronological sequence, strewn with dashes and irregularly capitalized, and often extremely elliptical in their language. Three years later, Johnson edited and published, along with Theodora Ward, a complete collection of Dickinson's letters.

Poetry

Dickinson's poems generally fall into three distinct periods, the works in each period having certain general characters in common.

- Pre-1861. These are often conventional and sentimental in nature. Thomas H. Johnson, who later published The Poems of Emily Dickinson, was able to date only five of Dickinson's poems before 1858. Two of these are mock valentines done in an ornate and humorous style, and two others are conventional lyrics, one of which is about missing her brother Austin. The fifth poem, which begins "I have a Bird in spring", conveys her grief over the feared loss of friendship and was sent to her friend Sue Gilbert.

- 1861–1865. This was her most creative period—these poems are more vigorous and emotional. Johnson estimated that she composed 86 poems in 1861, 366 in 1862, 141 in 1863, and 174 in 1864. He also believed that this is when she fully developed her themes of life and death.

- Post-1866. It is estimated that two-thirds of the entire body of her poetry was written before this year.

-

|

Original wording

A narrow Fellow in the Grass

Occasionally rides –

You may have met Him – did you not

His notice sudden is –

|

Republican version

A narrow Fellow in the Grass

Occasionally rides –

You may have met Him – did you not,

His notice sudden is.

|

|

As Farr points out, "snakes instantly notice you"; Dickinson's version captures the "breathless immediacy" of the encounter; and The Republican's punctuation renders "her lines more commonplace". With the increasingly close focus on Dickinson's structures and syntax has come a growing appreciation that they are "aesthetically based". Although Johnson's landmark 1955 edition of poems was relatively unaltered from the original, later scholars critiqued it for deviating from the style and layout of Dickinson's manuscripts. Meaningful distinctions, these scholars assert, can be drawn from varying lengths and angles of dash, and differing arrangements of text on the page. Several volumes have attempted to render Dickinson's handwritten dashes using many typographic symbols of varying length and angle. R. W. Franklin's 1998 variorum edition of the poems provided alternate wordings to those chosen by Johnson, in a more limited editorial intervention. Franklin also used typeset dashes of varying length to approximate the manuscripts' dashes more closely.

Major themes

Dickinson left no formal statement of her aesthetic intentions and, because of the variety of her themes, her work does not fit conveniently into any one genre. She has been regarded, alongside Emerson (whose poems Dickinson admired), as a

Transcendentalist. However, Farr disagrees with this analysis saying that Dickinson's "relentlessly measuring mind ... deflates the airy elevation of the Transcendental". Apart from the major themes discussed below, Dickinson's poetry frequently uses humor, puns, irony and satire.

- Flowers and gardens. Farr notes that Dickinson's "poems and letters almost wholly concern flowers" and that allusions to gardens often refer to an "imaginative realm ... wherein flowers [are] often emblems for actions and emotions". She associates some flowers, like gentians and anemones, with youth and humility; others with prudence and insight. Her poems were often sent to friends with accompanying letters and nosegays. Farr notes that one of Dickinson's earlier poems, written about 1859, appears to "conflate her poetry itself with the posies": "My nosegays are for Captives – / Dim – long expectant eyes – / Fingers denied the plucking, / Patient till Paradise – / To such, if they sh'd whisper / Of morning and the moor – / They bear no other errand, / And I, no other prayer".

- The Master poems. Dickinson left a large number of poems addressed to "Signor", "Sir" and "Master", who is characterized as Dickinson's "lover for all eternity". These confessional poems are often "searing in their self-inquiry" and "harrowing to the reader" and typically take their metaphors from texts and paintings of Dickinson's day. The Dickinson family themselves believed these poems were addressed to actual individuals but this view is frequently rejected by scholars. Farr, for example, contends that the Master is an unattainable composite figure, "human, with specific characteristics, but godlike" and speculates that Master may be a "kind of Christian muse".

- Morbidity. Dickinson's poems reflect her "early and lifelong fascination" with illness, dying and death. Perhaps surprisingly for a New England spinster, her poems allude to death by many methods: "crucifixion, drowning, hanging, suffocation, freezing, premature burial, shooting, stabbing and guillotinage". She reserved her sharpest insights into the "death blow aimed by God" and the "funeral in the brain", often reinforced by images of thirst and starvation. Dickinson scholar Vivian Pollak considers these references an autobiographical reflection of Dickinson's "thirsting-starving persona", an outward expression of her needy self-image as small, thin and frail. Dickinson's most psychologically complex poems explore the theme that the loss of hunger for life causes the death of self and place this at "the interface of murder and suicide".

- Gospel poems. Throughout her life, Dickinson wrote poems reflecting a preoccupation with the teachings of Jesus Christ and, indeed, many are addressed to him. She stresses the Gospels' contemporary pertinence and recreates them, often with "wit and American colloquial language". Scholar Dorothy Oberhaus finds that the "salient feature uniting Christian poets ... is their reverential attention to the life of Jesus Christ" and contends that Dickinson's deep structures place her in the "poetic tradition of Christian devotion" alongside Hopkins, Eliot and Auden. In a Nativity poem, Dickinson combines lightness and wit to revisit an ancient theme: "The Savior must have been / A docile Gentleman – / To come so far so cold a Day / For little Fellowmen / The Road to Bethlehem / Since He and I were Boys / Was leveled, but for that twould be / A rugged billion Miles –".

- The Undiscovered Continent. Academic Suzanne Juhasz considers that Dickinson saw the mind and spirit as tangible visitable places and that for much of her life she lived within them. Often, this intensely private place is referred to as the "undiscovered continent" and the "landscape of the spirit" and embellished with nature imagery. At other times, the imagery is darker and forbidding—castles or prisons, complete with corridors and rooms—to create a dwelling place of "oneself" where one resides with one's other selves. An example that brings together many of these ideas is: "Me from Myself – to banish – / Had I Art – / Impregnable my Fortress / Unto All Heart – / But since myself—assault Me – / How have I peace / Except by subjugating / Consciousness. / And since We're mutual Monarch / How this be / Except by Abdication – / Me – of Me?".

Legacy

Emily Dickinson is now considered a powerful and persistent figure in American culture. Although much of the early reception concentrated on Dickinson's eccentric and secluded nature, she has become widely acknowledged as an innovative pre-modernist poet. As early as 1891, William Dean Howells wrote that "If nothing else had come out of our life but this strange poetry we should feel that in the work of Emily Dickinson, America, or New England rather, had made a distinctive addition to the literature of the world, and could not be left out of any record of it." Twentieth-century critic Harold Bloom has placed her alongside Walt Whitman, Wallace Stevens, Robert Frost, T. S. Eliot and Hart Crane as a major American poet.

|

|

| Poetry Coffee Cup Cafe |

|

|

|

| Home Page |

|

|

|

| Poetry Main Index Page |

|

|

|

| Email Us by clicking the Image |

|

|

West St Paul Antiques is:

Open year round

New - Winter Hours & Summer Hours

Winter Hours

Open Monday - Saturday 10 - 5

Sunday 12 - 4 October - March

Summer Hours

Open Wednesday - Saturday 10 - 5

Closed Sunday-Tuesday's April - September

|

|

| Click the Image |

|

|

|

| Email me with your feedback on how I can Improve this website. |

|

|

|