|

| Peyton Randolph

Henry Middleton

John Hancock

Henry Laurens

John Jay

Samuel Huntington

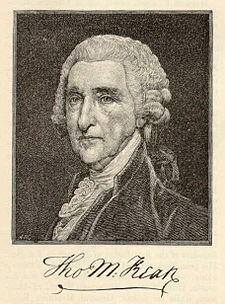

Thomas McKean

|

|

|

The Forgotten Presidents

of the Continental Congresses and the United States

under the Articles of Confederation.

|

|

|

| Peyton Randolph |

|

| |

|

Peyton Randolph (Born ca. 1721, died 1775) - Served the First Continental Congress from September 5, 1774 until October 21, 1774 and the Second Continental Congress from May 10, 1775 to May 24, 1775, resigning due to ill health, and succeeded by John Hancock.

When he returned to Williamsburg after presiding over the Continental Congress in 1775, Peyton Randolph was on the black list of patriots the redcoats proposed to arrest and hang. The city's volunteer company of militia offered him its protection in an address that concluded: "MAY HEAVEN GRANT YOU LONG TO LIVE THE FATHER OF YOUR COUNTRY, AND THE FRIEND TO FREEDOM AND HUMANITY!"

If his friend George Washington succeeded him to the title of America's patrimonial honors, Randolph nevertheless did as much as any Virginian to bring the new nation into the world. He presided over every important Virginia assembly in the years leading to the Revolution, was among the first of the colony's great men to oppose the Stamp Act, chaired the first meeting of the delegates of 13 colonies at Philadelphia in 1774, and chaired the second in 1775.

He had been born 54 years before--probably in Williamsburg--the second son of Sir John and Lady Susannah Randolph. His first name was his maternal grandmother's maiden name, just as his older brother Beverley's was their mother's. The surname Randolph identified him as a scion of 18th-century Virginia's most powerful clan.

When he was three or four years old, the family moved into the imposing wooden home on Market Square now known as the Peyton Randolph House. His father, among Virginia's most distinguished attorneys, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, and a wealthy man, died when Peyton was 16, leaving the house and other property for him in trust with his mother. The will also gave Peyton his father's extensive library in the hope he would "betake himself to the study of law." By then, he had a brother John and a sister Mary.

Attentive to his father's wishes, he attended the College of William and Mary, then learned the law in London's Inns of Court. He entered the Middle Temple on October 13, 1739, and took a place at the bar February 10, 1743. Returning to Williamsburg, he was appointed the colony's attorney general by Governor William Gooch on May 7, 1744. His father had filled the office before him, and his brother would assume the role after.

When he turned 24, Randolph reached the age set for his inheritance. On March 8, 1746, he married Betty Harrison, and on July 21 (more than two years after his return), he qualified himself for the private practice of law in York County.

His cousin Thomas Jefferson may have shed some light on the delay in a character sketch he wrote of Randolph years later. "He was indeed a most excellent man," Jefferson said, but "heavy and inert in body, he was rather too indolent and careless for business."

He was, as well, occupied with myriad public duties. In 1747 he became a vestryman of Bruton Parish Church, in 1748 Williamsburg's representative in the house of Burgesses, and in 1749 a justice of the peace. He returned to the House in 1752 as the burgess for the college, and on December 15, 1753, the house hired him as its special agent for some ticklish business in London.

Soon after he arrived in Virginia in 1751, Governor Robert Dinwiddie had begun to exercise a right no governor had before: the imposition of a fee for certifying land patents. For his signature, Dinwiddie demanded a pistole, a Spanish coin worth about 20 shillings. Regarding the fee as an unauthorized tax, Virginians objected, though to no result.

Peyton Randolph was dispatched to England as the house's agent, with directions to go over the governor's head. But as attorney general, it was his duty to represent the interests of the Crown, of which Dinwiddie was the principal representative in Virginia. Randolph was attacking the right of the governor he was appointed to defend.

The governor refused to give Peyton Randolph permission to leave the colony, but he left anyway. In London, he had to answer for his action, and he was ousted from the attorney general's office. Dinwiddie had already named George Wythe as acting attorney general in Randolph's place.

Nevertheless, the London officials pointedly suggested that Dinwiddie reconsider his fee and said that they would have no objection to Peyton Randolph's reinstatement if he apologized. So he did, and subsequently resumed office soon after his return to Williamsburg.

Reelected burgess for the college in 1755, he involved himself the next year in a somewhat ludicrous, though harmless, attempt to promote morale during the French and Indian War. With other prominent men, he formed the Associators, a group to raise and pay bounties for private troops to join the regular force at Winchester. George Washington, in charge of the fort there, wasn't sure what he would do with the untrained men if they arrived. Not enough came, however, to cause any inconvenience.

In 1757, Randolph joined the college's board, and he served as a rector for one year. He was reelected burgess for Williamsburg in 1761, and thus entered the phase of his life that thrust him into a leadership role in the Revolution.

Word of Parliament's intended Stamp Act brought Virginians and their burgesses into conflict with the Crown itself in 1764. Peyton Randolph was appointed chairman of a committee to draft protests to the king, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons maintaining the colony's exclusive right of self-taxation.

The responsibility put him at odds with Patrick Henry, the Virginian most noted for opposition to the tax. At the end of the legislative session in 1765, Henry, a freshman, introduced seven resolutions against the act. Peyton Randolph, George Wythe, and others thought that Henry's resolutions added nothing to the colony's case and that their consideration was improper until the colony had a reply to its earlier protests.

In the final days of the session, after many opponents had left the city, Patrick Henry introduced his measures and made his "Caesar-Brutus" speech. Peyton Randolph, though not yet Speaker, was presiding. When Speaker John Robinson resumed the chair the following day (May 30), Henry carried five of his resolves by a single ballot. A tie would have allowed Robinson to cast the deciding "nay." Jefferson, standing at the chamber door, said Peyton Randolph emerged saying, "By God, I would have given one hundred guineas for a single vote."

Patrick Henry left town, and the next day his fifth (and most radical) resolution was expunged by the burgesses who remained. Nevertheless, it was reprinted with the others in newspapers across the colonies as if it stood.

Peyton Randolph was elected Speaker on November 6, 1766, succeeding the deceased Robinson and defeating Richard Henry Lee. Peyton's brother John succeeded him as attorney general the following June. By now the brothers had begun to disagree politically; John's conservatism would take him to England in 1775 while Peyton joined the rebellion.

Another set of Patrick Henry's resolves, against the Townshend Duties, came before the House in May 1769. This time Peyton Randolph approved their passage, but Governor Botetourt did not. He dissolved the assembly. The "former representatives of the people," as they called themselves, met the next day at the Raleigh Tavern with Speaker Peyton Randolph in the chair. They adopted a compact drafted by George Mason and introduced by George Washington against the importation of British goods. Speaker Randolph was the first to sign.

When the new legislature met in the winter, the governor was pleased to announce the repeal of all of the Townshend Duties, except the small one on tea. Legislative attention turned to other, calmer affairs. The next summer Peyton Randolph became chairman of the building committee for the Public Hospital.

Tempers flared again in 1773, when Great Britain proposed to transport a band of Rhode Island smugglers to England for trial. The implications for Virginia were troublesome, and the burgesses appointed a standing Committee of Correspondence and Inquiry with Speaker Peyton Randolph as chairman. The following May brought word of the closing of the port of Boston in retaliation for its Tea Party.

On May 24, 1774, Robert Carter Nicholas introduced a resolution drafted by Thomas Jefferson that read:

"This House, being deeply impressed with apprehension of the great dangers, to be derived to British America, from the hostile Invasion of the City of Boston, in our Sister Colony of Massachusetts bay, whose commerce and harbour are, on the first Day of June next, to be stopped by an Armed force, deem it highly necessary that the said first day of June be set apart, by the Members of this House, as a day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, devoutly to implore the divine interposition for averting the heavy Calamity which threatens destruction to our Civil Rights, and the Evils of civil War; to give us one heart and one Mind to firmly oppose, by all just and proper means, every injury to American Rights; and that the Minds of his Majesty and his parliament, may be inspired from above with Wisdom, Moderation, and Justice, to remove from the loyal People of America, all cause of danger, from a continued pursuit of Measure, pregnant with their ruin."

It was adopted.

Governor Dunmore summoned the house on May 26 and told Peyton Randolph: "Mr. Speaker and Gentlemen of the House of Burgesses, I have in my hand a paper published by order of your House, conceived in such terms as reflect highly upon His Majesty and the Parliament of Great Britain, which makes it necessary for me to dissolve you; and you are accordingly dissolved."

On May 27, 1775, 89 burgesses gathered again at the Raleigh Tavern to form another nonimportation association, and the following day the Committee of Correspondence proposed a Continental Congress. Twenty-five burgesses met at Peyton Randolph's house on May 30 and scheduled a state convention to be held on August 1 to consider a proposal from Boston for a ban on exports to England.

Peyton Randolph led the community to Bruton Parish Church on June 1 to pray for Boston, and soon he was organizing a Williamsburg drive to send provisions and cash for its relief. The First Virginia Convention approved the export ban and elected as delegates to the Congress Peyton Randolph, Richard Henry Lee, George Washington, Patrick Henry, Richard Bland, Benjamin Harrison, and Edmund Pendleton.

On August 18, 1774, before he left Williamsburg, Peyton Randolph wrote his will, leaving his property to the use of his wife for life. They had no children. The property was to be auctioned after her death and the proceeds divided among Randolph's heirs.

When the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774 Thomas Lynch of South Carolina nominated Peyton Randolph to be chairman. He was elected by unanimous vote, and so became the first President of the united colonies. Delegate Silas Deane wrote Mrs. Deane: "Designed by nature for the business, of an affable, open and majestic deportment, large in size, though not out of proportion, he commands respect and esteem by his very aspect, independent of the high character he sustains."

In October 21, 1774, Peyton Randolph returned to Williamsburg to preside at an impending meeting of the house. Repeatedly postponed, it did not meet until the following June. Nonetheless, on November 9 Peyton Randolph accepted a copy of the Continental Association banning trade with England signed by nearly 500 merchants gathered in Williamsburg.

Peyton Randolph was in the chair again at the Second Virginia Convention in Richmond on March 23 when Patrick Henry rose and made his "Liberty or Death" speech in favor of the formation of a statewide militia. In reaction Governor Dunmore removed the gunpowder from Williamsburg's Magazine on April 21. Alerted to the theft, a mob gathered at the Courthouse. Peyton Randolph was one of the leaders who persuaded the crowd to disperse and averted violence.

Peyton Randolph led the Virginia delegation to the Second Continental Congress in May 1775, and he again took the chair as president. Due to ill health he resigned 14 days later. General Thomas Gage, commander of British forces in America, had been issued blank warrants for the execution of rebel leaders and a list of names with which to fill them. Peyton Randolph's name was on the list. He returned to Williamsburg under guard, and the town bells pealed to announce his safe arrival. The militia escorted him to his house and pledged to guarantee his safety.

The Third Virginia Convention reelected its speaker to Congress in July 1775, and Randolph left for Philadelphia in late August or early September. By this time, John Hancock had succeeded him to its chair.

About 8 p.m. on Sunday, October 23, 1775, Peyton Randolph began to choke, a side of his face contorted, and he died of an "apoplectic stroke." He was buried that Tuesday at Christ's Church in Philadelphia. His nephew, Edmund Randolph, brought his remains to Williamsburg in 1776, and he was interred in the family crypt in the Chapel at the College of William and Mary on November 26.

Peyton Randolph's estate was auctioned on February 19, 1783, after Betty Randolph's death. Thomas Jefferson bought his books. Among them were bound records dating to Virginia's earliest days that still are consulted by historians. Added to the collection at Monticello that Jefferson sold to the federal government years later, they became part of the core of the Library of Congress.

|

|

|

| Peyton Randolph |

|

33rd Speaker of the Virginia House of Burgesses |

In office

1766 1775 |

| Preceded by |

John Robinson |

| Succeeded by |

Office abolished |

1st and 3rd President of the Continental Congress |

In office

September 5, 1774 October 22, 1774 |

In office

May 10, 1775 May 24, 1775 |

|

| Born |

September 10, 1721(1721-09-10)

Williamsburg, Virginia |

| Died |

October 22, 1775 (aged 54)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Signature |

|

|

|

|

Early life

Randolph was born in Virginia to a prominent family. His parents were Sir John Randolph and Susannah Beverley; his brother was John Randolph. He was also the grandson of William Randolph.

Randolph attended the College of William and Mary, and later studied law at Middle Temple at the Inns of Court in London, becoming a member of the bar in 1743.

Political career

Randolph returned to Williamsburg after he became a member of the bar, and was appointed Attorney General of the Colony of Virginia the next year.

He served several terms in the Virginia House of Burgesses, beginning in 1748. It was Randolph's dual roles as attorney general and as burgess that would lead to an extraordinary conflict of interest in 1751.

The new governor, Robert Dinwiddie, had imposed a fee for the certification of land patents, which the House of Burgesses strongly objected to. The House selected Peyton Randolph to represent their cause to Crown authorities in London. In his role as attorney general, though, he was responsible for defending actions taken by the governor. Randolph left for London, over the objections of Governor Dinwiddie, and was replaced for a short time as attorney general. He was reinstated on his return at the behest of officials in London, who also recommended the Governor drop the new fee.

In 1765 Randolph found himself at odds with a freshman burgess, Patrick Henry, over the matter of a response to the Stamp Act. The House appointed Randolph to draft objections to the act, but his more conservative plan was trumped when Henry obtained passage of five of his seven Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions. This was accomplished at a meeting of the House in which most of the members were absent, and over which Randolph was presiding in the absence of the Speaker.

Randolph resigned as attorney general in 1766. As friction between Britain and the colonies progressed, he became more in favor of independence. In 1769 the House of Burgesses was dissolved by the Governor in response to its actions against the Townshend Acts. Randolph had been Speaker at the time. Afterwards, he chaired meetings of a group of former House members at a Williamsburg tavern, which worked toward responses to the unwelcome tax measures imposed by the British government.

Continental Congress and later life

Randolph was elected as presiding officer in both the First and Second Continental Congresses, in large part due to his reputation for leadership while in the House of Burgesses. He did not, however, live to see American independence; Randolph died in Philadelphia, and was buried at Christ Church. He was later re-interred at the College of William and Mary chapel.

Randolph County, North Carolina, formed in 1779, and two United States Navy ships called USS Randolph were named in his honor, as is the Peyton Randolph elementary school in Arlington, Virginia.

Randolph's house survives and is a U.S. National Historic Landmark. Known as Peyton Randolph House, it is shown to the public as part of the Colonial Williamsburg complex.

Family ties

- His nephew, Edmund Randolph, became the first United States Attorney General.

- His wife was the sister of Benjamin Harrison V.

- His first cousin once removed was President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph's husband Thomas Mann Randolph was a descendant of Peyton's uncle Richard Randolph and his wife Jane Bolling, a descendant of Pocahontas.

- His first cousin twice removed was Supreme Court Justice John Marshall.

- His niece Lucy Grymes married Virginia Governor Thomas Nelson Jr. Her first cousin once removed, also named Lucy Grymes, married Henry Lee II (who was in fact Peyton Randolph's first cousin once removed), and was the mother of Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee, who was the father of Confederate General Robert Edward Lee.

- He is also related to the Confederate Generals Fitzhugh Lee, Edmund Jennings Lee, Nelson Pendelton Lee, and Richard L. Page; and to US Admiral Samuel P. Lee.

- Confederate General John Pegram married Hetty Cary, a cousin to the Randolphs.

|

|

|

| Henry Middleton |

|

| |

Henry Middleton (1717-1784) - Served October 22, 1774 to October 26, 1774

In 1741, Henry Middleton married Mary Williams, only daughter and heiress of John Williams, a wealthy landowner, Justice of the Peace and member of the Assembly. Mary's dowry included the house and plantation that he and Mary named Middleton Place. Here, rather than at The Oaks, they made their home. Henry Middleton was one of the most influential political leaders of his time. He held a number of high offices, was Speaker of the Commons, Commissioner for Indian Affairs, and a member of the Governor's Council until he resigned his seat in 1770 to become a leader of the opposition to British policy. He was chosen to represent South Carolina in the First Continental Congress and on October 22, 1774, was elected its President in the absence of Peyton Randolph. By this time, Henry was among the wealthiest landholders in South Carolina with more than 50,000 acres and approximately 800 slaves. For the last twenty-three years of his life he lived at his earlier home, The Oaks, returning there after the death of his wife Mary in 1761. Henry twice remarried, but his five sons and seven daughters were all children of his first wife. He relinquished Middleton Place to Arthur, his eldest son and heir.

|

Henry Middleton

Henry Middleton (1717 June 13, 1784) of South Carolina was the second President of the Continental Congress from October 22, 1774, until Peyton Randolph was able to resume his duties briefly beginning on May 10, 1775. His father was Acting South Carolina Governor (1725-1730) Arthur Middleton (1681-1737).

While a delegate to the Continental Congress, Middleton resigned in order to prepare for the coming war. He was succeeded by his son Arthur Middleton (1742-1787), who went on to sign the United States Declaration of Independence.

Arthur's son, also named Henry (1770-1846), had a long career in politics. He was Governor of South Carolina (1810-1812), U.S. Representative (1815-1819), and the Minister to Russia (1820-1830).

Several of Henry's other children married well:

- Hester was married to S.C. Lt. Governor Charles Drayton {See below}-grandson of South Carolina Governor William Bull. {Federal Judge William Drayton, Sr. was father of Charles Drayton and Congressman William Drayton; the Drayton brothers were cousins of Congressman William Henry Drayton. W.H. Drayton father of US Navy Captain Percival Drayton and CS General Thomas Fenwick Drayton.

- Mary Polly was married to Congressman Pierce Butler. Mary Butler was the daughter of Col. Thomas Middleton. She was Henry's cousin.

- Henrietta was married to Governor Edward Rutledge.

- Sarah was the first wife of Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Charles Pinckney's brother Thomas Pinckney's son Thomas Pinckney Jr married Elizabeth Izard, a distant cousin of Congressman Ralph Izard. (Charles and Thomas Pinckney's sister Harriott was married to Daniel Horry, whose daughter married a son of South Carolina Governor John Rutledge. They were thus connected to the Grimkι; Huger; Drayton; Laurens families of South Carolina and the Forten family of Philadelphia).

- Thomas married Anne Manigault. Their daughter Esther married Ralph Stead Izard, a distant cousin of South Caroina Congressman Ralph Izard and Alice De Lancey. (Alice was a niece of James DeLancey; James DeLancey's sister Susannah was the wife of Sir Peter Warren (Admiral). James DeLancey's daughter Anne was a wife of loyalist Thomas Jones (historian)). Another daughter, Elizabeth Middleton, was married to Ralph DeLancey Izard, son of Congressman Ralph Izard.

(Note: Joseph, a brother of Anne Manigault, was first married to a daughter of Arthur Middleton and Mary Izard; by Joseph Manigault's second marriage to Charlotte Drayton he was the father of Confederate General Arthur Middleton Manigault (1824-1886), whose wife was a cousin 1st removed of Confederate General Benjamin Huger. Charlotte Drayton was the daughter of Charles Drayton and Hester Middleton

|

|

|

| John Hancock |

|

| |

|

John Hancock (1737 - 1793) - Served May 24, 1775 to October 29, 1777,

and again from November 23, 1885 to June 5, 1786.

The third president was a patriot, rebel leader, merchant who signed his name into immortality in giant strokes on the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. The boldness of his signature has made it live in American minds as a perfect expression of the strength and freedom - and defiance - of the individual in the face of British tyranny. As President of the Continental Congress during two widely spaced terms - the first from May 24 1775 to October 30 1777 and elected the second time from November 23 1885 to May 29, 1786, never having served due to continued illness

Hancock was the presiding officer when the members approved the Declaration of Independence. Because of his position, it was his official duty to sign the document first - but not necessarily as dramatically as he did. Hancock figured prominently in another historic event - the battle at Lexington: British troops who fought there April 10, 1775, had known Hancock and Samuel Adams were in Lexington and had come there to capture these rebel leaders.

And the two would have been captured, if they had not been warned by Paul Revere. As early as 1768, Hancock defied the British by refusing to pay customs charges on the cargo of one of his ships. One of Boston's wealthiest merchants, he was recognized by the citizens, as well as by the British, as a rebel leader - and was elected President of the first Massachusetts Provincial Congress. After he was chosen President of the Continental Congress in 1775, Hancock became known beyond the borders of Massachusetts, and, having served as colonel of the Massachusetts Governor's Guards he hoped to be named commander of the American forces - until John Adams nominated George Washington. In 1778 Hancock was commissioned Major General and took part in an unsuccessful campaign in Rhode Island. But it was as a political leader that his real distinction was earned - as the first Governor of Massachusetts, as President of Congress, and as President of the Massachusetts constitutional ratification convention. He helped win ratification in Massachusetts, gaining enough popular recognition to make him a contender for the newly created Presidency of the United States, but again he saw Washington gain the prize. Like his rival, George Washington, Hancock was a wealthy man who risked much for the cause of independence. He was the wealthiest New Englander supporting the patriotic cause, and, although he lacked the brilliance of John Adams or the capacity to inspire of Samuel Adams, he became one of the foremost leaders of the new nation - perhaps, in part, because he was willing to commit so much at such risk to the cause of freedom

|

John Hancock

| John Hancock |

Portrait by John Singleton Copley, c. 1770–72, Massachusetts Historical Society |

President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress

|

In office

1774 – 1775 |

President of the Continental Congress

|

In office

May 24, 1775 – October 31, 1777 |

1st and 3rd Governor of Massachusetts

|

|---|

In office

October 25, 1780 – January 29, 1785

May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793 |

|

| Born |

January 23, 1737(1737-01-23)

Quincy, Massachusetts |

|---|

| Died |

October 8, 1793 (aged 56)

Quincy, Massachusetts |

|---|

| Spouse(s) |

Dorothy Quincy |

|---|

| Signature |

|

|---|

John Hancock (January 23, 1737 – October 8, 1793) was a merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that "John Hancock" became, in the United States, a synonym for "signature".

Before the American Revolution, Hancock was one of the wealthiest men in the Thirteen Colonies, having inherited a profitable shipping business from his uncle. Hancock began his political career in Boston as a protégé of Samuel Adams, an influential local politician, though the two men would later become estranged. As tensions between colonists and Great Britain increased in the 1760s, Hancock used his wealth to support the colonial cause. He became very popular in Massachusetts, especially after British officials seized his sloop Liberty in 1768 and charged him with smuggling. Although the charges against Hancock were eventually dropped, he has often been described as a smuggler in historical accounts, but the accuracy of this characterization has been questioned.

Hancock was one of Boston's leaders during the crisis that led to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War in 1775. He served more than two years in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and as president of Congress was the first to sign the Declaration of Independence. Hancock returned to Massachusetts and was elected as governor of the Commonwealth for most of his remaining years. He used his influence to ensure that Massachusetts ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.

Early life

John Hancock was born on January 23, 1737; according to the Old Style calendar then in use, the date was January 12, 1736. His birthplace was Braintree, Massachusetts, in a part of town which eventually became the separate city of Quincy. He was the son of the Reverend John Hancock of Braintree and Mary Hawke Thaxter, who was from nearby Hingham. As a child, Hancock became a casual acquaintance of young John Adams, whom the Reverend Hancock had baptized in 1734. The Hancocks lived a comfortable life, and owned one slave to help with household work.

After Hancock's father died in 1744, John was sent to live with his uncle and aunt, Thomas Hancock and Lydia (Henchman) Hancock. Thomas Hancock was the proprietor of a firm known as the House of Hancock, which imported manufactured goods from Britain and exported rum, whale oil, and fish. Thomas Hancock's highly successful business made him one of Boston's richest and best-known residents. He and Lydia lived in Hancock Manor on Beacon Hill, an imposing estate with several servants and slaves. The couple, who did not have any children of their own, became the dominant influence on John's life.

After graduating from the Boston Latin School in 1750, Hancock enrolled in Harvard University and received a bachelors degree in 1754. Upon graduation, he began to work for his uncle, just as the French and Indian War (1754–1763) had begun. Thomas Hancock had close relations with the royal governors of Massachusetts, and secured profitable government contracts during the war. John Hancock learned much about his uncle's shipping business during these years, and was trained for eventual partnership in the firm. Hancock worked hard, but he also enjoyed playing the role of a wealthy aristocrat, and developed a fondness for expensive clothes.

From 1760 to 1761, Hancock lived in England while building relationships with customers and suppliers. Back in Boston, Hancock gradually took over the House of Hancock as his uncle's health failed, becoming a full partner in January 1763. He became a member of the Masonic Lodge of St. Andrew in October 1762, which connected him with many of Boston's most influential citizens. When Thomas Hancock died in August 1764, John inherited the business, Hancock Manor, two or three household slaves, and thousands of acres of land, becoming one of the wealthiest men in the colonies. The household slaves continued to work for John and his aunt, but were eventually freed through the terms of Thomas Hancock's will; there is no evidence that John Hancock ever bought or sold slaves.

Growing imperial tensions

After its victory in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the British Empire was deep in debt. Looking for new sources of revenue, the British Parliament sought, for the first time, to directly tax the colonies, beginning with the Sugar Act of 1764. The act provoked outrage in Boston, where it was widely viewed as a violation of colonial rights. Men such as James Otis and Samuel Adams argued that because the colonists were not represented in Parliament, they could not be taxed by that body; only the colonial assemblies, where the colonists were represented, could levy taxes upon the colonies. Hancock was not yet a political activist, however: he criticized the tax for economic, rather than constitutional, reasons.

Around 1772, Hancock commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint this portrait of Samuel Adams, Hancock's early political mentor.

Hancock emerged as a leading political figure in Boston just as tensions with Great Britain were increasing. In March 1765, he was elected as one of Boston's five selectmen, an office previously held by his uncle for many years. Soon after, Parliament passed the 1765 Stamp Act, a wildly unpopular measure in the colonies that produced riots and organized resistance. Hancock initially took a moderate position: as a loyal British subject, he thought that the colonists should submit to the act, even though he believed that Parliament was misguided. Within a few months, Hancock had changed his mind, although he continued to disapprove of violence and the intimidation of royal officials by mobs. Hancock joined the resistance to the Stamp Act by participating in a boycott of British goods, which made him popular in Boston. After Bostonians learned of the impending repeal of the Stamp Act, Hancock was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in May 1766.

Hancock's political success benefited from the support of Samuel Adams, the clerk of the House of Representatives and a leader of Boston's "popular party", also known as "Whigs" and later as "Patriots". The two men made an unlikely pair. Fifteen years older than Hancock, Adams had a somber, Puritan outlook that stood in marked contrast to Hancock's taste for luxury and extravagance. Some traditional stories suggest that Adams masterminded Hancock's political ascendancy so that the merchant's great wealth could be used to further Adams's agenda. In some of these tales, Hancock is portrayed as shallow and vain, easily manipulated by Adams. In other versions, Hancock is moderate and reasonable, while Adams is radical and dangerous. Historian William M. Fowler, who wrote biographies of both men, argued that these stories contain a grain of truth, but are mostly folklore. Fowler characterized the relationship between the two as symbiotic, with Adams as the mentor and Hancock the protégé.

Townshend Acts crisis

After the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament took a different approach to raising revenue, passing the 1767 Townshend Acts, which established new duties on various imports and strengthened the customs agency by creating the American Customs Board. The British government believed that a more efficient customs system was necessary because many colonial American merchants had been smuggling. Smugglers violated the Navigation Acts by trading with ports outside of the British Empire and avoiding import taxes. Parliament hoped that the new system would reduce smuggling and generate revenue for the government.

Colonial merchants, even those not involved in smuggling, found the new regulations oppressive. Other colonists protested that new duties were another attempt by Parliament to tax the colonies without their consent. Hancock joined other Bostonians in calling for a boycott of British imports until the Townshend duties were repealed. In their enforcement of the customs regulations, the Customs Board targeted Hancock, Boston's wealthiest Whig. They may have suspected that he was a smuggler, or they may have wanted to harass him because of his politics, especially after Hancock snubbed Governor Francis Bernard by refusing to attend public functions when the customs officials were present.

On April 9, 1768, two customs employees (called tidesmen) boarded Hancock's brig Lydia in Boston Harbor. Hancock was summoned, and finding that the agents lacked a writ of assistance (a general search warrant), did not allow them to go below deck. When one of them later managed to get into the hold, Hancock's men forced the tidesman back on deck. Customs officials wanted to file charges, but the case was dropped when Massachusetts Attorney General Jonathan Sewell ruled that Hancock had broken no laws. Later, some of Hancock's most ardent admirers would call this incident the first act of physical resistance to British authority in the colonies and credit Hancock with initiating the American Revolution.

Liberty affair

The next incident proved to be a major event in the coming of the American Revolution. On the evening of May 9, 1768, Hancock's sloop Liberty arrived in Boston Harbor, carrying a shipment of Madeira wine. When custom officers inspected the ship the next morning, they found that it contained 25 pipes of wine, just one fourth of the ship's carrying capacity. Hancock paid the duties on the 25 pipes of wine, but officials suspected that he had arranged to have additional pipes of wine unloaded during the night to avoid paying the duties for the entire cargo. They did not have any evidence to prove this, however, since the two tidesmen who had stayed on the ship over night gave a sworn statement that nothing had been unloaded.

Portrait of Hancock by John Singleton Copley, c. 1765

One month later, while the British warship HMS Romney was in port, one of the tidesmen changed his story: he now claimed that he had been forcibly held on the Liberty while it had been illegally unloaded. On June 10, customs officials seized the Liberty, which had since been loaded with new cargo, and towed it out to the Romney. Bostonians, already angry because the captain of the Romney had been impressing sailors in Boston Harbor, began to riot. The next day, customs officials, claiming that they were unsafe in town, relocated to the Romney, and then to Castle William, an island fort in the harbor.

Hancock was involved in two lawsuits stemming from the Liberty incident: an in rem suit against the ship, and an in personam suit against himself. As was the custom, any penalties assessed by the court would be awarded to the governor, the informer, and the Crown, each getting a third. The first suit, filed on June 22, 1768, resulted in the confiscation of the Liberty in August. Customs officials then used the ship to enforce trade regulations until it was burned by angry colonists in Rhode Island the following year.

The second trial began in October 1768, when charges were filed against Hancock and five others for allegedly unloading 100 pipes of wine from the Liberty without paying the duties. If convicted, the defendants would have had to pay a penalty of triple the value of the wine, which came to £9,000. With John Adams serving as his lawyer, Hancock was prosecuted in a highly publicized trial by a vice admiralty court, which had no jury and did not always allow the defense to cross-examine the witnesses. After dragging out for nearly five months, the proceedings against Hancock were dropped without explanation.

The Liberty incident created two popular images of Hancock: supporters celebrated him as a martyr to the Patriot cause, while critics portrayed him as a scheming smuggler. Historians have been similarly divided. "Hancock's guilt or innocence and the exact charges against him", wrote historian John W. Tyler in 1986, "are still fiercely debated." Historian Oliver Dickerson argued that Hancock was the victim of an essentially criminal racketeering scheme perpetrated by Governor Bernard and the customs officials. Dickerson believed that there is no reliable evidence that Hancock was guilty in the Liberty case, and that the purpose of the trials was to punish Hancock for political reasons and to plunder his property. Opposed to Dickerson's interpretation were Kinvin Wroth and Hiller Zobel, the editors of John Adams's legal papers, who argued that "Hancock's innocence is open to question", and that the British officials acted legally, if unwisely.

Aside from the Liberty affair, the degree to which Hancock was engaged in smuggling, which was widespread in the colonies, has been questioned. Given the clandestine nature of smuggling, records are naturally scarce. If Hancock was a smuggler, no documentation of this has been found. John W. Tyler identified 23 smugglers in his study of more than 400 merchants in revolutionary Boston, but found no written evidence that Hancock was one of them. Biographer William Fowler concluded that while Hancock was probably engaged in some smuggling, most of his business was legitimate, and his reputation as the "king of the colonial smugglers" is a myth without foundation.

Massacre to Tea Party

Paul Revere's 1768 engraving of British troops arriving in Boston was reprinted throughout the colonies.

The Liberty affair reinforced a previously made British decision to suppress unrest in Boston with a show of military might. The decision had been prompted by Samuel Adams's 1768 Circular Letter, which was sent to other British American colonies in hopes of coordinating resistance to the Townshend Acts. Lord Hillsborough, secretary of state for the colonies, sent four regiments of the British Army to Boston to support embattled royal officials, and instructed Governor Bernard to order the Massachusetts legislature to revoke the Circular Letter. Hancock and the Massachusetts House voted against rescinding the letter, and instead drew up a petition demanding Governor Bernard's recall. When Bernard returned to England in 1769, Bostonians celebrated.

The British troops remained, however, and tensions between soldiers and civilians eventually resulted in the killing of five civilians in the so-called Boston Massacre of March 1770. Hancock was not involved in the incident, but afterwards he led a committee to demand the removal of the troops. Meeting with Bernard's successor, Governor Thomas Hutchinson, and the British officer in command, Colonel William Dalrymple, Hancock claimed that there were 10,000 armed colonists ready to march into Boston if the troops did not leave. Hutchinson knew that Hancock was bluffing, but the soldiers were in a precarious position when garrisoned within the town, and so Dalrymple agreed to remove both regiments to Castle William. Hancock was celebrated as a hero for his role in getting the troops withdrawn. His reelection to the Massachusetts House in May was nearly unanimous.

This portrait of Hancock was published in England in 1775.

After Parliament partially repealed the Townshend duties in 1770, Boston's boycott of British goods ended. Politics became quieter in Massachusetts, although tensions remained. Hancock tried to improve his relationship with Governor Hutchinson, who in turn sought to woo Hancock away from Adams's influence. In April 1772, Hutchinson approved Hancock's election as colonel of the Boston Cadets, a militia unit whose primary function was to provide a ceremonial escort for the governor and the General Court. In May, Hutchinson even approved of Hancock's election to the Council, the upper chamber of the General Court, whose members were elected by the House but subject to veto by the governor. Hancock's previous elections to the Council had been vetoed, but now Hutchinson allowed the election to stand. Hancock declined the office, however, not wanting to appear to have been co-opted by the governor. Nevertheless, Hancock used the improved relationship to resolve an ongoing dispute. To avoid hostile crowds in Boston, Hutchinson had been convening the legislature outside of town; now he agreed to allow the General Court to sit in Boston once again, to the relief of the legislators.

Hutchinson had dared to hope that he could win over Hancock and discredit Adams. To some, it seemed that Adams and Hancock were indeed at odds: when Adams formed the Boston Committee of Correspondence in November 1772 to advocate colonial rights, Hancock declined to join, creating the impression that there was a split in the Whig ranks. But whatever their differences, Hancock and Adams came together again in 1773 with the renewal of major political turmoil. They cooperated in the revelation of private letters of Thomas Hutchinson, in which the governor seemed to recommend "an abridgement of what are called English liberties" to bring order to the colony. The Massachusetts House, blaming Hutchinson for the military occupation of Boston, called for his removal as governor.

Even more trouble followed Parliament's passage of the 1773 Tea Act. On November 5, Hancock was elected as moderator at a Boston town meeting that resolved that anyone who supported the Tea Act was an "Enemy to America". Hancock and others tried to force the resignation of the agents who had been appointed to receive the tea shipments. Unsuccessful in this, they attempted to prevent the tea from being unloaded after three tea ships had arrived in Boston Harbor. Hancock was at the fateful meeting on December 16, where he reportedly told the crowd, "Let every man do what is right in his own eyes." Hancock did not take part in the Boston Tea Party that night, but he approved of the action, although he was careful not to publicly praise the destruction of private property.

Over the next few months, Hancock was disabled by gout, which would trouble him with increasing frequency in the coming years. By March 5, 1774, he had recovered enough to deliver the fourth annual Massacre Day oration, a commemoration of the Boston Massacre. Hancock's speech denounced the presence of British troops in Boston, who he said had been sent there "to enforce obedience to acts of Parliament, which neither God nor man ever empowered them to make". The speech, probably written by Hancock in collaboration with Adams, Joseph Warren, and others, was published and widely reprinted, enhancing Hancock's stature as a leading Patriot.

Revolution begins

Parliament responded to the Tea Party with the Boston Port Act, one of the so-called Coercive Acts intended to strengthen British control of the colonies. Hutchinson was replaced as governor by General Thomas Gage, who arrived in May 1774. On June 17, the Massachusetts House elected five delegates to send to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, which was being organized to coordinate colonial response to the Coercive Acts. Hancock did not serve in the first Congress, possibly for health reasons, or possibly to remain in charge while the other Patriot leaders were away.

Gage soon dismissed Hancock from his post as colonel of the Boston Cadets. In October 1774, Gage canceled the scheduled meeting of the General Court. In response, the House resolved itself into the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, a body independent of British control. Hancock was elected as president of the Provincial Congress and was a key member of the Committee of Safety. The Provincial Congress created the first minutemen companies, consisting of militiamen who were to be ready for action on a moment's notice. A revolution had begun.

Wary of returning to Boston, Hancock was staying at this house in Lexington when the Revolutionary War began.

On December 1, 1774, the Provincial Congress elected Hancock as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress to replace James Bowdoin, who had been unable to attend the first Congress because of illness. Before Hancock reported to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, the Provincial Congress unanimously reelected him as their president in February 1775. Hancock's multiple roles gave him enormous influence in Massachusetts, and as early as January 1774 British officials had considered arresting him. After attending the Provincial Congress in Concord in April 1775, Hancock and Samuel Adams decided that it was not safe to return to Boston before leaving for Philadelphia. They stayed instead at Hancock's childhood home in Lexington.

On April 14, 1775, Gage received a letter from Lord Dartmouth advising him "to arrest the principal actors and abettors in the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion".

On the night of April 18, Gage sent out a detachment of soldiers on the fateful mission that would spark the American Revolutionary War. The purpose of the British expedition was to seize and destroy military supplies that the colonists had stored in Concord. According to many historical accounts, Gage also instructed his men to arrest Hancock and Adams, but, as historian John Alden pointed out in 1944, the written orders issued by Gage made no mention of arresting the Patriot leaders. Gage apparently decided that he had nothing to gain by arresting Hancock and Adams, since other leaders would simply take their place, and the British would be portrayed as the aggressors.

Although Gage had evidently decided against seizing Hancock and Adams, Patriots initially believed otherwise. From Boston, Joseph Warren dispatched messenger Paul Revere to warn Hancock and Adams that British troops were on the move and might attempt to arrest them. Revere reached Lexington around midnight and gave the warning. Hancock, still considering himself a militia colonel, wanted to take the field with the Patriot militia at Lexington, but Adams and others convinced him to avoid battle, arguing that he was more valuable as a political leader than as a soldier. As Hancock and Adams made their escape, the first shots of the war were fired at Lexington and Concord. Soon after the battle, Gage issued a proclamation granting a general pardon to all who would "lay down their arms, and return to the duties of peaceable subjects"—with the exceptions of Hancock and Samuel Adams. Singling out Hancock and Adams in this manner only added to their renown among Patriots.

President of Congress

Dorothy Quincy, by John Singleton Copley, c. 1772

With the war underway, Hancock made his way to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia with the other Massachusetts delegates. On May 24, 1775, he was unanimously elected President of the Continental Congress, succeeding Peyton Randolph after Henry Middleton declined the nomination. Hancock was a good choice for president for several reasons. He was experienced, having often presided over legislative bodies and town meetings in Massachusetts. His wealth and social standing inspired the confidence of moderate delegates, while his association with Boston radicals made him acceptable to other radicals. His position was somewhat ambiguous, because the role of the president was not fully defined, and it was not clear if Randolph had resigned or was on a leave of absence. Like other presidents of Congress, Hancock's authority was limited to that of a presiding officer. He also had to handle a great deal of official correspondence, and he found it necessary to hire clerks at his own expense to help with the paperwork. In Congress on June 15, 1775, Massachusetts delegate John Adams nominated George Washington as commander in chief of the army then gathered around Boston. Many years later, Adams wrote that Hancock had shown great disappointment at not getting the command for himself. If true, Hancock did not let his disappointment interfere with his duties, and he always showed admiration and support for General Washington, even though Washington politely declined Hancock's request for a military appointment.

When Congress recessed on August 1, 1775, Hancock took the opportunity to wed his fiancée, Dorothy "Dolly" Quincy. The couple was married on August 28 in Fairfield, Connecticut John and Dorothy would have two children, neither of whom survived to adulthood. Their daughter Lydia Henchman Hancock was born in 1776 and died ten months later. Their son John George Washington Hancock was born in 1778 and died in 1787 after falling down and hitting his head while ice skating.

Hancock served in Congress through some of the darkest days of the Revolutionary War. The British drove Washington from New York and New Jersey in 1776, which prompted Congress to flee to Baltimore, Maryland. Hancock and Congress returned to Philadelphia in March 1777, but were compelled to flee six months later when the British occupied Philadelphia. Hancock wrote innumerable letters to colonial officials, raising money, supplies, and troops for Washington's army. He chaired the Marine Committee, and took pride in helping to create a small fleet of American frigates, including the USS Hancock, which was named in his honor.

Signing the Declaration

Hancock was president of Congress when the Declaration of Independence was adopted and signed. He is primarily remembered by Americans for his large, flamboyant signature on the Declaration, so much so that "John Hancock" became, in the United States, an informal synonym for signature. According to legend, Hancock signed his name largely and clearly so that King George could read it without his spectacles, but this fanciful story did not appear until many years later.

Hancock's signature as it appears on the engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence

Contrary to popular mythology, there was no ceremonial signing of the Declaration on July 4, 1776. After Congress approved the wording of the text on July 4, a copy was sent to be printed. As president, Hancock may have signed the document that was sent to the printer, but this is uncertain because that document is lost, perhaps destroyed in the printing process. The printer produced the first published version of the Declaration, the widely distributed Dunlap broadside. Hancock, as President of Congress, was the only delegate whose name appeared on the broadside, which meant that until a second broadside was issued six months later with all of the signers listed, Hancock was the only delegate whose name was publicly attached to the treasonous document. Hancock sent a copy of the Dunlap broadside to George Washington, instructing him to have it read to the troops "in the way you shall think most proper".

Hancock's name was printed, not signed, on the Dunlap broadside; his iconic signature appears on a different document—a sheet of parchment that was carefully handwritten sometime after July 19 and signed on August 2 by Hancock and those delegates present. Known as the engrossed copy, this is the famous document on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Return to Massachusetts

In John Trumbull's famous painting The Declaration of Independence, Hancock, as presiding officer, is seated on the right as the drafting committee presents their work.

In October 1777, after more than two years in Congress, President Hancock requested a leave of absence. He asked George Washington to arrange a military escort for his return to Boston. Although Washington was short on manpower, he nevertheless sent fifteen horsemen to accompany Hancock on his journey home. By this time Hancock had become estranged from Samuel Adams, who disapproved of what he viewed as Hancock's vanity and extravagance, which Adams believed were inappropriate in a republican leader. When Congress voted to thank Hancock for his service, Adams and the other Massachusetts delegates voted against the resolution, as did a few delegates from other states.

Back in Boston, Hancock was reelected to the House of Representatives. As in previous years, his philanthropy made him popular. Although his finances had suffered greatly because of the war, he gave to the poor, helped support widows and orphans, and loaned money to friends. According to biographer William Fowler, "John Hancock was a generous man and the people loved him for it. He was their idol." In December 1777, he was reelected as a delegate to the Continental Congress and as moderator of the Boston town meeting

Hancock rejoined the Continental Congress in Pennsylvania in June 1778, but his brief time there was unhappy. In his absence, Congress had elected Henry Laurens as its new president, which was a disappointment to Hancock, who had hoped to reclaim his chair. Hancock got along poorly with Samuel Adams, and missed his wife and newborn son. On July 9, 1778, Hancock and the other Massachusetts delegates joined the representatives from seven other states in signing the Articles of Confederation; the remaining states were not yet prepared to sign, and the Articles would not be ratified until 1781.

Hancock returned to Boston in July 1778, motivated by the opportunity to finally lead men in combat. Back in 1776, he had been appointed as the senior major general of the Massachusetts militia. Now that the French fleet had come to the aid of the Americans, General Washington instructed General John Sullivan of the Continental Army to lead an attack on the British garrison at Newport, Rhode Island, in August 1778. Hancock nominally commanded 6,000 militiamen in the campaign, although he let the professional soldiers do the planning and issue the orders. It was a fiasco: French Admiral d'Estaing abandoned the operation, after which Hancock's militia mostly deserted Sullivan's Continentals. Hancock suffered some criticism for the debacle but emerged from his brief military career with his popularity intact.

After much delay, the new Massachusetts Constitution finally went into effect in October 1780. To no one's surprise, Hancock was elected Governor of Massachusetts in a landslide, winning over 90% of the vote. He governed Massachusetts through the end of the Revolutionary War and into an economically troubled postwar period. Hancock took a hands-off approach to governing, avoiding controversial issues as much as possible. According to William Fowler, Hancock "never really led" and "never used his strength to deal with the critical issues confronting the commonwealth".

Hancock was easily reelected to annual terms as governor, until his surprise resignation on January 29, 1785. Hancock cited his failing health as the reason, but he may also have been aware of growing unrest in the countryside and wanted to get out of office before the trouble came. Hancock's critics often suspected that he suffered from "political gout", which is when an official allegedly uses an illness to avoid a difficult political situation. The turmoil that Hancock avoided became known as Shays' Rebellion, which Hancock's successor James Bowdoin had to deal with. After the uprising, Hancock was reelected in 1787, and he promptly pardoned all the rebels. Hancock was reelected to annual terms as governor for the remainder of his life.

Final years

Hancock's memorial in Boston's Granary Burying Ground, erected in 1896.

When he had resigned as governor in 1785, Hancock was again elected as a delegate to the Continental Congress, known as the Confederation Congress after the ratification of the Articles of Confederation in 1781. Congress had declined in importance after the Revolutionary War, and was frequently ignored by the states. Congress elected Hancock to serve as its president, but he never attended because of his poor health and because he was not interested. He sent Congress a letter of resignation in 1786.

In 1787, in an effort to remedy the perceived defects of the Articles of Confederation, delegates met at the Philadelphia Convention and drafted the United States Constitution, which was then sent to the states for ratification or rejection. Hancock, who was not present at the Philadelphia Convention, had misgivings about the new Constitution's lack of a bill of rights and its shift of power to a central government. In January 1788, Hancock was elected president of the Massachusetts ratifying convention, although he was ill and not present when the convention began. Hancock mostly remained silent during the contentious debates, but as the convention was drawing to close, he gave a speech in favor of ratification. For the first time in years, Samuel Adams supported Hancock's position. Even with the support of Hancock and Adams, the Massachusetts convention narrowly ratified the Constitution by a vote of 187 to 168. Hancock's support was probably a deciding factor in the ratification.

Hancock was put forth as a candidate in the 1789 U. S. presidential election. As was the custom in an era where political ambition was viewed with suspicion, Hancock did not campaign or even publicly express interest in the office; he instead made his wishes known indirectly. Like everyone else, Hancock knew that George Washington was going to be elected as the first president, but Hancock may have been interested in being vice president, despite his poor health. Hancock received only four electoral votes in the election, however, none of them from his home state; the Massachusetts electors all voted for another native son, John Adams, who became the vice president. Hancock was disappointed with his poor showing, but he remained as popular as ever in Massachusetts.

His health failing, Hancock spent his final few years as essentially a figurehead governor. With his wife at his side, he died in bed on October 8, 1793, at fifty-six years of age. By order of acting governor Samuel Adams, the day of Hancock's burial was a state holiday; the lavish funeral was perhaps the grandest given to an American up to that time.

Legacy

Hancock's famous signature on the stern of the destroyer USS John Hancock

Many places and things in the United States have been named in honor of John Hancock. The U.S. Navy has named vessels USS Hancock and USS John Hancock; a World War II Liberty ship was also named in his honor. Ten states have a Hancock County named for him; other places named after him include Hancock, Massachusetts; Hancock, Michigan; Hancock, New York; and Mount Hancock in New Hampshire. The John Hancock Insurance company, founded in Boston in 1862, was also named for him; it had no connection to Hancock's own business ventures. The insurance company has passed on the name to famous office buildings such as the John Hancock Tower in Boston and the John Hancock Center in Chicago, and the John Hancock Student Village at Boston University.

|

- John Hancock at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

| Political offices |

Preceded by

none |

President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress

1774 1775 |

Succeeded by

Joseph Warren |

Preceded by

Peyton Randolph |

President of the Continental Congress

May 24, 1775 October 31, 1777 |

Succeeded by

Henry Laurens |

Preceded by

William Howe

(Provincial governor) |

Governor of Massachusetts

October 25, 1780 January 29, 1785 |

Succeeded by

Thomas Cushing

(acting) |

Preceded by

James Bowdoin |

Governor of Massachusetts

May 30, 1787 October 8, 1793 |

Succeeded by

Samuel Adams |

| Political offices |

Preceded by

none |

President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress

1774 1775 |

Succeeded by

Joseph Warren |

Preceded by

Peyton Randolph |

President of the Continental Congress

May 24, 1775 October 31, 1777 |

Succeeded by

Henry Laurens |

Preceded by

William Howe

(Provincial governor) |

Governor of Massachusetts

October 25, 1780 January 29, 1785 |

Succeeded by

Thomas Cushing

(acting) |

Preceded by

James Bowdoin |

Governor of Massachusetts

May 30, 1787 October 8, 1793 |

Succeeded by

Samuel Adams |

|

|

Presidents of the Continental Congress |

|

| First Continental Congress |

Peyton Randolph · Henry Middleton |

|

| Second Continental Congress |

Peyton Randolph · John Hancock · Henry Laurens · John Jay · Samuel Huntington |

|

| Confederation Congress |

Samuel Huntington · Thomas McKean · John Hanson · Elias Boudinot · Thomas Mifflin · Richard Henry Lee · John Hancock1 · David Ramsay · Nathaniel Gorham · Nathaniel Gorham · Arthur St. Clair · Cyrus Griffin |

|

|

Signers of the Declaration of Independence |

|

|

J. Adams S. Adams Bartlett Braxton Carroll Chase Clark Clymer Ellery Floyd Franklin Gerry Gwinnett Hall Hancock Harrison Hart Hewes Heyward Hooper Hopkins Hopkinson Huntington Jefferson F. Lee R. Lee Lewis Livingston Lynch McKean Middleton L. Morris R. Morris Morton Nelson Paca Paine Penn Read Rodney Ross Rush Rutledge Sherman Smith Stockton Stone Taylor Thornton Walton Whipple Williams Wilson Witherspoon Wolcott Wythe |

|

|

|

Signers of the Articles of Confederation |

|

|

A. Adams · S. Adams · T. Adams · Banister · Bartlett · Carroll · Clingan · Collins · Dana · Dickinson · Drayton · Duane · Duer · Ellery · Gerry · Hancock · Hanson · Harnett · Harvie · Heyward · Holten · Hosmer · Huntington · Hutson · Langworthy · Laurens · F. Lee · R. Lee · Lewis · Lovell · Marchant · Mathews · McKean · G. Morris · R. Morris · Penn · Reed · Roberdeau · Scudder · Sherman · Smith · Telfair · Van Dyke · Walton · Wentworth · Williams · Witherspoon · Wolcott |

|

|

|

Governors of Massachusetts |

|

|

| |

|

| Colony |

Endecott · Winthrop · T. Dudley · Haynes · Vane · Winthrop · T. Dudley · Bellingham · Winthrop · Endecott · T. Dudley · Winthrop · Endecott · T. Dudley · Endecott · Bellingham · Endecott · Bellingham · Leverett · Bradstreet |

|

| Dominion (16861689) |

J. Dudley · Andros · Bradstreet |

|

| Province (16921776) |

W. Phips · Stoughton · Coote · Stoughton · Governor's Council · J. Dudley · Governor's Council · J. Dudley · Tailer · Shute · Dummer · Burnet · Dummer · Tailer · Belcher · Shirley · S. Phips · Shirley · S. Phips · Governor's Council · Pownall · Hutchinson · Bernard · Hutchinson · Gage |

|

Commonwealth

(since 1776) |

Hancock · Cushing · Bowdoin · Hancock · Adams · Sumner · Gill · Governor's Council · Strong · Sullivan · Lincoln, Sr. · Gore · Gerry · Strong · Brooks · Eustis · Morton · Lincoln, Jr. · Davis · Armstrong · Everett · Morton · Davis · Morton · Briggs · Boutwell · Clifford · E. Washburn · Gardner · Banks · Andrew · Bullock · Claflin · W. Washburn · Talbot · Gaston · Rice · Talbot · Long · Butler · Robinson · Ames · Brackett · Russell · Greenhalge · Wolcott · Crane · Bates · Douglas · Guild · Draper · Foss · Walsh · McCall · Coolidge · Cox · Fuller · Allen · Ely · Curley · Hurley · Saltonstall · Tobin · Bradford · Dever · Herter · Furcolo · Volpe · Peabody · Volpe · Sargent · Dukakis · King · Dukakis · Weld · Cellucci · Swift · Romney · Patrick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Henry Laurens |

|

| |

Henry Laurens (1724 - 1792) - Served from November 1, 1777 until December 9, 1778.

The only American president ever to be held as a prisoner of war by a foreign power, Laurens was heralded after he was released as "the father of our country," by no less a personage than George Washington. He was of Huguenot extraction, his ancestors having come to America from France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes made the Reformed faith illegal. Raised and educated for a life of mercantilism at his home in Charleston, he also had the opportunity to spend more than a year in continental travel. It was while in Europe that he began to write revolutionary pamphlets - gaining him renown as a patriot. He served as vice-president of South Carolina in1776. He was then elected to the Continental Congress. He succeeded John Hancock as President of the newly independent but war beleaguered United States on November 1, 1777. He served until December 9, 1778 at which time he was appointed Ambassador to the Netherlands. Unfortunately for the cause of the young nation, he was captured by an English warship during his cross-Atlantic voyage and was confined to the Tower of London until the end of the war. After the Battle of Yorktown, the American government regained his freedom in a dramatic prisoner exchange - President Laurens for Lord Cornwallis. Ever the patriot, Laurens continued to serve his nation as one of the three representatives selected to negotiate terms at the Paris Peace Conference in 1782.

|

Henry Laurens

| Henry Laurens |

|

President of the Continental Congress |

In office

1777 1778 |

| Preceded by |

John Hancock |

| Succeeded by |

John Jay |

|

| Born |

March 6, 1724(1724-03-06)

Charleston, South Carolina |

| Died |

December 8, 1792 (aged 71)

Charleston, South Carolina |

| Signature |

|

Henry Laurens (March 6, 1724 [O.S. February 24, 1723] December 8, 1792) was an American merchant and rice planter from South Carolina who became a political leader during the Revolutionary War. A delegate to the Second Continental Congress Laurens succeeded John Hancock as President of the Second Continental Congress. Laurens ran the largest slave trading house in North America. In the 1750s alone, his Charleston firm oversaw the sale of more than 8,000 enslaved Africans. He was for a time Vice-President of South Carolina and a diplomat.

Personal life

Henry was born to John and Esther Grasset Laurens in Charleston, South Carolina. According to the Julian calendar, Laurens was born on February 24, 1723/4; according to the Gregorian calendar, which was adopted in Britain and its colonies during Laurens' lifetime, he was born on March 6, 1724. His father was a saddler and his parents had come to Charles Town as part of the Huguenot immigration, drawn by the promise of religious liberty. His family prospered, and in 1744 Henry went to England where he learned the ways of commerce from a merchant who had formerly lived in Charleston.

Henry returned to Charleston in 1747. He entered the import and export business and became a prosperous merchant, slave trader, and planter. Laurens was the Charleston business agent for the London-based owners of Bunce Island, a British slave castle in the Sierra Leone River in West Africa. Laurens received slave ships arriving in Charleston, advertised the sale of slaves in the newspaper, organized the auctions, and took a 10% commission on each sale. He sold African slaves to local rice planters, but also purchased some for his own plantations.

...in 1747 he opened an import and export business in Charles Town. Through his London contacts, Laurens entered into the slave trade with the Grant, Oswald & Company who controlled 18th century British slave castle in the Republic of Sierra Leone, West Africa known as Bunce Castle. Laurens contracted to receive slaves from Serra Leone, catalogue and marketed the human product conducting public auctions in Charles Town. Laurens also engaged in the import and export of many other products but his 10% commission from the slave auctions proved to be his major source of his income. By 1750, Laurens was wealthy enough to win the hand of Eleanor Ball, the daughter of a very wealthy rice plantation owner. Laurens, who was also a rice planter, used his auction profits to purchase exceptional South Carolina farmland and slaves to expand his agricultural pursuits. This strategy culminated in his assemblage of the Mepkin Plantation where along with his mercantile pursuits Laurens earned a fortune.

On June 25, 1750 Laurens married Eleanor Ball, the daughter of another wealthy rice planter and slave owner. Of the couple's twelve children, eight died in infancy or childhood.

- John Laurens served as a military aide to General Washington and was killed in the Revolutionary War. During the war, John proposed a plan under which a small number of slaves would be enlisted in the American forces and eventually granted their freedom. In a private letter, Henry gently sought to persuade John that this plan was impractical.

- Martha Laurens married David Ramsay, a physician, historian, and South Carolina Congressman.

- Henry Jr. married Eliza, the daughter of John Rutledge, and inherited his father's estate.

- Mary married Charles Pinckney and died in childbirth soon afterwards.

In 1772, Henry, like many successful American merchants, began to buy farmland. He purchased 3,000 acres (12 km²) at Mepkin. Although he later bought another 20,000 acres (81 km²) including new rice-growing lands opening up in coastal Georgia, Mepkin became the family seat. By 1776 he had given up his mercantile ventures, although he always ran his plantations in a very business-like way.

Political career

1. General George Washington 2. General Horatio Gates 3. Dr. Benjamin Franklin 4. Henry Laurens, as President of the Continental Congress. 5. John Paul Jones / D. Berger sculp. 1784.

Laurens served in the militia, as did most able-bodied men in his time. He rose to the rank of Lt. Colonel in the campaigns against the Cherokee Indians in 1757-1761. 1757 also marked the first year he was elected to the colonial assembly. He was elected again every year but one until the revolution replaced the assembly with a state Convention as an interim government. The year he missed was 1773 when he visited England to arrange for his children's education. He wascolony's Council in 1764 and 1768, but declined both times. In 1772 he joined the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, and carried on some extensive correspondence with other members.

As the American Revolution neared, Laurens was at first inclined to support reconciliation with the British Crown. But as conditions deteriorated he came to fully support the American position. When Carolina began the creation of a revolutionary government, he was elected to the Provincial Congress which first met on January 9, 1775. He was president of the Committee of Safety, and presiding officer of that congress from June until March of 1776. When South Carolina installed a full independent government, he served as the Vice President of South Carolina from March of 1776 to June 27, 1777.

Henry Laurens was first named a delegate to the Continental Congress on January 10, 1777. He served in the Congress from then until 1780. He was the President of the Continental Congress from November 1, 1777 to December 9, 1778.

In the fall of 1779 the Congress named Laurens their minister to Holland. In early 1780 he took up that post and successfully negotiated Dutch support for the war. But on his return voyage to Amsterdam that fall the British Navy intercepted his ship, the Continental packet Mercury, off the banks of Newfoundland. Although her dispatches were tossed in the water, they were retrieved by the British, who discovered the draft of a possible U.S.-Dutch treaty prepared by William Lee. This prompted Britain to declare war on the Netherlands, the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.

Laurens was charged with treason, transported to England, and imprisoned in the Tower of London, (the only American ever held prisoner in the Tower). This became another issue between the British and Americans. In the field, most captives were regarded as prisoners of war, and while conditions were frequently appalling, prisoner exchanges and mail privileges were accepted practice. During his imprisonment Laurens was assisted by Richard Oswald, his former business partner and the principal owner of Bunce Island. Oswald argued on Laurens' behalf to the British government. Finally, on December 31, 1781 he was released in exchange for General Lord Cornwallis and completed his voyage.

In 1783 Laurens was in Paris as one of the Peace Commissioners for the negotiations leading to the Treaty of Paris. While he didn't sign the primary treaty, he was instrumental in reaching the secondary accords that resolved issues involving the Netherlands and Spain. Ironically, Richard Oswald, Laurens' old business partner in the slave trade, was the principal negotiator for the British during the Paris peace talks. Laurens generally retired from public life in 1784. He was sought for a return to the Continental Congress, the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and the state assembly, but he declined all of these jobs. He did serve in the state convention of 1788 where he voted to ratify the United States Constitution.

Later events

The British forces from Charleston had burned the main home at Mepkin during the war. When Henry returned in 1784, the family lived in an outbuilding while the manor was rebuilt. He lived there the rest of his life, working to recover the estimated £40,000 that the revolution had cost him. (This would be equivalent to about $3,500,000 in 2000 values). He died at Mepkin, and afterward was cremated and his ashes were interred there. The estate at Mepkin passed through several hands, but large portions of the estate still exist, and are now a Trappist abbey.

The city of Laurens, South Carolina and its county are named for him. General Lachlan McIntosh, who worked for Laurens as a clerk and became close friends with him, named Fort Laurens, in Ohio, after him. Laurens County, Georgia is named for his son, who preceded him in death.

|

|

|

| John Jay |

|

| |

John Jay (1745 - 1829) - Served from December 10, 1778 to September 27, 1779.