|

| The III Marine Expeditionary Force |

|

|

|

| III Marine Amphibious Force |

|

|

The amphibious force was reactivated as the III Marine Expeditionary Force in the Republic of Vietnam on May 7, 1965, and consisted of the 3d Marine Division and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. III MEF was later redesignated as III Marine Amphibious Force. On March 15, 1966, Force Logistics Command was formed at Da Nang and joined the III MEF. Expansion of Marine Forces in Vietnam continued in 1966 with the arrival of the 1st Marine Division. By May 1967, the area under Marine control had expanded to more than 1,700 square miles, encompassing 183 villages, and increasing the number of civilians under RVN control by more than one million. In April, 1971, the headquarters of III MEF left Vietnam for Okinawa.

On April 12, 1975, the 31st Marine Amphibious Unit, a task group of III MEF, executed Operation Eagle Pull in which 287 U.S. and foreign nationals were evacuated from Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Weeks later, the 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade, a task force of the III MEF successfully extracted by helicopter more than 7,000 Americans and Vietnamese from Saigon, Vietnam, in Operation Frequent Wind. In conjunction with the later operation, Marine detachments from III MEF provided security of U.S. ships engaged in carrying Vietnamese refugees to Guam. Within days, Marines of III MEF were again called on to assist in the recovery of the USS Mayaguez from Cambodia. Elements of the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, and 9th Marines, were flown to an advanced staging of a joint U.S. Task Force. There, they conducted a helo assault on the Cambodian island of Koh Tang where the Mayaguez was being held. The crew and ship were recovered on May 15, and the III MEF units returned to Okinawa.

On Feb. 5, 1988, the III MEF was redesignated to III Marine Expeditionary Force. III MEF units have supported a host of contingency operations, and routinely participate in joint, combined and bilateral exercises with Asian and Pacific countries like Thailand, Korea, Australia, and the Philippines. Nearly 8,000 III MEF Marines deployed in support of Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm in Southwest Asia. III MEF units were instrumental in the success of Operation Sea Angel in Bangladesh, and during disaster relief operations in the Republic of the Philippines following the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. III MEF Marines provided disaster relief in the wake of the earthquake in Kobe, Japan, in 1995.

|

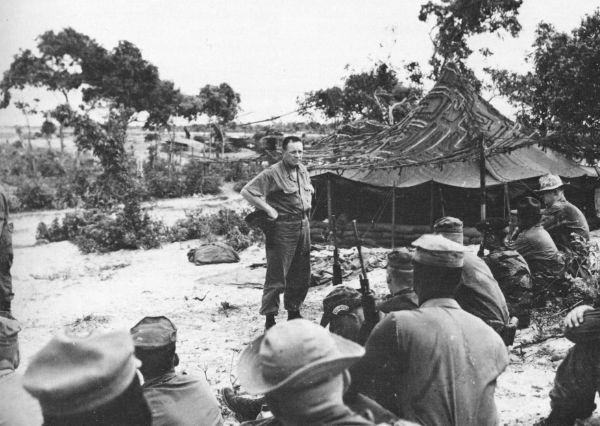

Brigadier General Karch (center, 1st row) poses with members of his 9th MEB staff at Da Nang. The 9th MEB was shortly afterwards deactivated and replaced by the newly formed III MAF,

in the area and report its physical properties so a decision could be made whether to put rubber tired or tracked equipment in the area. The report indicated rubber tired equipment, therefore the 'Snafu.' I never did find out whether they gave a wrong analysis or took the samples from the wrong site.46

A temporary impasse occurred on 9 May when the attempt was made to unload the airfield matting. The first lift, 68 tons, was placed on flatbed trailers and brought ashore by an LCU. The entire unloading came to a complete standstill; the heavily laden trucks could not move in the deep sand without assistance. The movement of the matting to the airfield site took five and a half hours. To try to expedite the process, the Navy beach group decided to break up the causeway installed on the south end of the beach and use the floating sections as makeshift barges. Approximately 200 bundles of matting could be loaded on one 'barge' which could then be floated to a point directly opposite the proposed airfield site, thereby reducing the movement distance. Although this eased the situation, the problem of movement on the beach remained. Finally, on 10 May, the 3d Marine Division provided an additional 2,500 feet of badly needed beach matting which somewhat alleviated the situation.

At noon on 12 May, the amphibious operation

* Colonel Graham was of the opinion that the markers that the Carl party found during their 3 April reconnaissance of Chu Lai may have been left by the civilian soil party, but General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., suggested that the markers may have been placed there during a reconnaissance of the beach area by the Marine 1st Force Reconnaissance Company. Col William M. Graham, Jr., Comments on draft MS, dtd 18Nov76 (Vietnam Comment File); Gen Wallace M. Greene, Jr., Comments on draft MS, dtd lAug77 (Vietnam Comment File). See Chapter 11, Reconnaissance Section, for an account of the 1st Force Reconnaissance Company's beach surveys of the Chu Lai area.

|

|

officially came to an end. On this date, the first dements of BLT 3/3, arriving in amphibious shipping from Okinawa, assumed defensive positions on the southern flank, relieving the 3d Reconnaissance Battalion. During the five-day period, 7-12 May, more than 10,925 tons of equipment and supplies had been unloaded and moved across the beach.

With the completion of the Chu Lai amphibious landing, seven of the nine infantry battalions of the 3d Marine Division, supported by most of the 12th Marines, the artillery regiment of the division, and a large portion of the 1st MAW were in South Vietnam. As a result, the 9th MEB was deactivated and replaced by a new Marine organization, the in Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF). *

*In the Pacific, one other change in designation of Marine units occurred during May. On the 25th, the 1st Marine Brigade (Rear) at Hawaii consisting of the brigade support elements under the command of Colonel Jack E. Hanthorn was redesignated the 1st Marine Brigade. Colonel Hanthorn relieved General Carl as brigade commander.

|

Formation and Development of III MAF

The Birth of III MAF-The Le My Experiment-Building the Chu Lai Airfield-III MAF in Transition-The Seeds of Pacification-June Operations in the Three Enclaves

The Birth of III MAF

The birth of III Marine Amphibious Force occurred almost simultaneously with the landing at Chu Lai. On 5 May, the Joint Chiefs relayed Presidential approval for the deployment to Da Nang of a Marine 'force/division/wing headquarters to include CG 3d Marine Division and 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. The following day, Major General Collins, who had remained in Vietnam after the Saigon meeting earlier in the month, assumed command of the Naval Component Command and also established the headquarters of the in Marine Expeditionary Force and the 3d Marine Division in Vietnam. The former 9th MEB commander, Brigadier General Karch, resumed his duties as assistant division commander and left for Okinawa to take over the units of the division remaining there. Brigadier General Carl became Deputy Commander, III MAF after the Chu Lai landing.

The III Marine Expeditionary Force became the III Marine Amphibious Force on 7 May. General Westmoreland had recommended to the Joint Chiefs that the Marines select a different designation for their command because the term 'Expeditionary' had unpleasant connotations for the Vietnamese, stemming from the days of the French Expeditionary Corps. The Joint Chiefs of Staff asked the Commandant, General Greene, to come up with another name. Although a III Marine Amphibious Corps had existed in the Pacific Theater during World War II, and was a logical choice for the name of the new Marine organization in Vietnam, several of the Commandant's advisors believed that the Vietnamese might take exception to the word 'Corps.' Consequently, General Greene chose the title in Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF) for the Marine forces in Vietnam and extended this revision to the Marine brigades.

One other major headquarters arrived at Da Nang during this period. On 11 May, Major General Fontana established a forward headquarters of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing in Vietnam (1st MAW Advance). Four days later, his Da Nang headquarters assumed command of all Marine aviation in the country. The Marine division/wing team was in Vietnam.

The expanded Marine force operated under guidelines provided by General Westmoreland. In his letter of instruction to General Collins, the MACV commander outlined the general mission of the Marines. They were directed to coordinate the defense of their three bases with General Thi; to render combat support to the South Vietnamese; to maintain the capability of conducting deep patrolling, offensive operations, and reserve reaction missions; and, finally, to carry out any contingency plans as directed by ComUSMACV.

The U.S. relationship with the Vietnamese military was a sensitive one. Since the Americans were the guests of the Vietnamese, they could offer advice to their allies, but could not compel action. Means had to be devised so that the two military forces could cooperate, but remain independent entities.

General Westmoreland elaborated further on this relationship between the U.S. and South Vietnamese commands in a message to Admiral Sharp. According to the MACV commander the requirement was for cooperation and agreement among senior commanders of different nationality groups. One of General Westmoreland's more intriguing phrases was that of 'tactical direction.' In actuality it was identical to operational control, but the general explained that tactical direction was a more palatable term to the Vietnamese. Westmoreland warned: 'U.S. commanders at all levels.

|

|

must accommodate to a new environment in which responsibility is shared and cooperatively discharged without benefit of traditional command relationship.' He emphasized that simple and easily understood plans were a prerequisite for success.

Taking these assumptions into consideration, General Westmoreland observed that American operations would take place in three successive stages: base security, deep patrolling, and finally search and destroy missions. For the Marines in Vietnam at this time base security was of the utmost concern; only at Da Nang had lu MAF begun to move into the second stage of operations.

The Le My Experiment

At Da Nang, the most significant development was the beginning of a rudimentary pacification program involving Lieutenant Colonel David A. Clement's 2d Battalion, 3d Marines. Since its arrival in April, the battalion had been on the high ground in the northwest fringe of the Da Nang TAOR, overlooking the village complex of Le My. The village consisted of a cluster of hamlets located on the southern bank of the Cu De River in the Hoa Vang District of Quang Nam Province, eight miles northwest of the Da Nang Airfield. According to the district chief, there had been little security in this area for over a year. Although the ARVN had conducted several operations, their forces had never remained to root out the Viet Cong political cadre and to provide security for the people.6 Security was one thing the Marines could furnish. Lieutenant Colonel Clement explained that the occupation of Le My gave him the needed depth of defense around the Da Nang Airbase to carry out his mission.

Beginning on 4 May, the Marines maintained pressure on the VC in the village complex by repeated patrolling of the area. On the 8th, Lieutenant Colonel Clement, accompanied by his S-

|

|

| In one of the first extensions of Marine positions into a populated area in May, Marines from the 2d Battalion, 3d Marines move into the hamlet of Le My. Three villagers watch the troops enter the village gate. |

|

|

The Marines roundup VC suspects in Le My. A South Vietnam Popular Force soldier is in the foreground.

2, Captain Lionel V. Silva, the district chief, Captain Nguyen Hoa, and the battalion's S-2 scouts, visited the hamlets.

They surveyed the neighborhood, talked to the villagers, but then came under Viet Cong fire, which killed one of the scouts. This incident confirmed Clement's opinion that in order to secure Le My, he first had to clear it.

On 11 May, the Marine battalion returned in strength. In an opposed fire fight, Cement's Company E 'conducted the assault . . . and cleared the hamlets. This time the battalion stayed and took up defensive positions in Le My. The Marines rounded up the male villagers who were put to work destroying punji traps, filling in trenches, and dismantling bunkers. Fifty of the men were sent to Da Nang for further questioning. Three days later, Vietnamese regional and popular forces relieved the Marines in the hamlets and the battalion moved to positions around the village. The actual eradication of the guerrillas was left to the South Vietnamese, while the Marines saturated the area with patrols and established ambushes to prevent the enemy from moving or massing forces.

To provide the villagers the means of fending for themselves, Clement's battalion trained the Vietnamese local forces, helped to prepare the defenses, and set up medical aid stations. The Marines emphasized self-help projects such as the building of schools and market places so that the local populace could continue on their own. Captain Silva, who was also Clement's civil affairs officer, stated that the battalion's goal was 'to create an administration, supported by the people, and capable of leading, treating, feeding, and protecting themselves by the time the battalion was moved to another area of operations.

The Marines also assisted the villagers in rebuilding two bridges, which, according to the

battalion's operations officer, Major Marc A. Moore, symbolized the spanning of the 'broken link in the road which separated territory previously controlled by the VC from the RVN controlled villages immediately south of Le My. Apparently well aware of this symbolism, a VC main force unit attacked one of the bridges on the night of 20 May. According to Lieutenant Colonel Clement, both the VC and the local population discovered the effectiveness of U. S security: 'The attack was repulsed, the bridge unharmed, and four VC were killed and abandoned.

The village held a dedication ceremony the next day at the two newly built bridges. Local government officials made speeches and cut a ribbon strung across the two spans. The festivities also presented grim reminders of the war; the chief displayed the bodies of the VC killed in the attack on the bridges at the gates of the village. This technique had been employed by both the government forces and the Communists to impress on the people what awaited the enemy.

At this early stage of the Marine intervention, the Le My experiment held promise for the future. General Collins stated that the 'Le My operation may well be the pattern for the employment of Marine Corps forces in this area. On a visit to III MAF in mid-May, General Krulak described the pacification efforts in Le My as a:

... beginning, but a good beginning. The people are beginning to get the idea that U.S. generated security is a long term affair. This is just one opportunity among many ... it is the expanding oil spot concept in action.

Building the Chu Lai Airfield

At Chu Lai, the main effort in May was the building of the airfield. On 7 May, Lieutenant Colonel Charles L. Goode, the 1st MAW engineering officer, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Wilson, the commanding officer of MABS-12, and a small advance party from the MABS arrived at Da Nang from Iwakuni. While at Da Nang, they discussed the Chu Lai airfield problem with Colonel Graham, the III MAF/3d Marine Division engineering officer. According to Goode, he brought Graham 'up to date on the runway layout and location as I knew it, including the fact that . . . [the civilian contractor] had not yet provided the coordinates of the runway.

The following morning, Lieutenant Colonel Goode and the MABS-12 advance party flew to Chu Lai. There they conferred with Commander Bannister, the NMCB-10 commander, and several members of his staff concerning the initial phases of the airfield construction. Commander Bannister informed Lieutenant Colonels Goode and Wilson that he had received a message from Saigon that listed the coordinates for the runway. The two Marines, with Bannister and his operations officer, then toured the area of the proposed location for the SATS field. According to Goode, 'the site was completely unacceptable.' It was several hundred yards west of the original site selected by General Carl during the reconnaissance of Chu Lai in April. Goode related:

. . . the line being surveyed at the time was on the west edge of the natural drainage course, which would have placed the cross taxiways, parallel taxiway and the entire operations area in the center of the drainage course. From the signs of water in the area, it was obvious that most of this area would be inundated during the rainy season.

Commander Bannister agreed with Lieutenant Colonel Goode's observations, but stated that he was

only following his instructions. The Seabee commander also told Goode that the message from Saigon indicated that a representative of the civilian construction firm would ' 'be on hand to advise on the specific locations to avoid interference with work on, and operations from, the permanent runway,' which the civilian firm was to construct. This representative never showed up.

To avoid further delays and to settle the question of the location of the SATS field once and for all, Lieutenant Colonel Goode attempted to contact General Carl on board the Estes, only to leam that the general had come ashore. Goode finally located General Carl at the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines CP. With Carl and members of the 3d MAB staff, Commander Bannister and Lieutenant Colonels Goode and Wilson returned to the proposed runway site. According to Carl's Chief of Staff, Colonel Nickerson, 'It was spontaneously determined by all that the intended location was not correct . . . . General Carl directed that a resurvey be made on the basis of the recommendations that he and the original survey group had made in April. The original site was on a plateau, just inland from a tree line and above the flood waterline, paralleling the sandy berm north of the landing beach. Only a shift of 500 yards to the north was necessary to avoid a low area just south of the mid-point of the runway. According to Goode, 'This caused no inconvenience because it was just moved to a point that was to be graded for the overrun in any event.

Seabees lay down aluminum for the SATS field. Two full crews were required for each 12-hour work shift to relieve each other at 30-minute intervals because of the heat and humidity.

Following the selection of the SATS site, Lieutenant Colonel Wilson's MABS-12 Marines and Commander Bannister's Seabee construction crews launched an intense struggle against time and nature. The initial planning envisioned an operational airfield by 28 May, 21 days after the landing. The Marines had relocated the 400 civilians who lived on or near the airfield site so that the construction could begin. Heat and humidity quickly sapped the strength of the work crews. Temperatures often climbed over the 100 degree mark and the humidity was not much less. The heavy earth moving equipment could be operated only by alternating crews every 30 minutes. During each 12-hour work shift, at least two full crews were necessary for each piece of machinery, but the work continued on a 24-hour basis.

Sand played havoc with the operation. It worked its way into everything; bearings, brake linings, and clutches were quickly ruined. At times more than half of the tractors and dump trucks were deadlined. Some of the frustrations encountered by the work crews were reflected in an informal log maintained by Lieutenant Colonel Goode:

9 May . . . My general impression of the entire day was that there was much wheel spinning, disorganization, and little work accomplished, all compounded by the fact that three of the C.B. TD-24 tractors went out of com-

|

mission-one because of a front PCV clutch and two for master clutches.

10 May . . . MCB-10 has provided MAG-12 (Adv.) with all the necessities. They even provided one jeep which broke down this afternoon .... Because of the continued shortage of tractors, TD-24s, I intend to ask C.O. 3/12 tomorrow if he can provide some to help.

11 May . . . Earth moving on the runway is going slowly. Three of the 6 C.B. TD-24's are deadlined. Two are for main clutches, none of which are available.

Eventually, the 3d Engineer Battalion at Da Nang contributed nearly all of its equipment to the Chu Lai construction, leaving the Marine engineers with only one bulldozer for their own use.

As the equipment situation gradually improved, the major problem for the contruction crews was that of soil stabilization. Initially, it was planned to mix sand and asphalt in order to form a firm base on which to lay the aluminum matting. On 14 May, Lieutenant Colonel Goode wrote: 'My biggest concern is the stabilization process. Will the rollers be capable of moving across the asphalt-treated surface? What will be the curing time?' On the 14th, Goode scheduled a test on the asphalt sand mixture in an area adjacent to the MABS command post so that the test site could be used as a helicopter pad after the test. On 15 May, Goode reported:

'The test of the asphalt failed completely. Asphalt was shot from a distributor onto the dry sand. There was practically no penetration. Twenty-four hours after the asphalt . . . was put down, it is still not cured.' After consulting with Colonel Graham, Lieutenant Colonel Goode decided that the solution for the problem was to stabilize the sand with a six-inch layer of laterite, a red ferrous soil obtained from pits north of the field.

On 16 May, the first piece of runway matting was laid on the north end of the strip. Hauling the red soil was time consuming and it was soon obvious that the runway would not be completed on the scheduled date. The Seabees and Marines were still confident that they could build a usable field by the target date by emplacing the arresting gear for landing and using jet-assisted takeoff (JATO) for the takeoffs. Soon it was evident that even this limited objective was in doubt. On 25 May, Lieutenant Colonel Goode wrote:

As of 1000 this date, there was in place 2,650 feet of matting leaving 650 feet of matting to be placed. One hundred fifty feet of taxiway is in place. A total of 1,200 feet of matting must be placed to meet the goal. Since matting started nine days ago, the average rate was 275 feet per day. The remainder would require that a rate of 400 feet per day be placed in the next three days ... It is questionable whether the goal can be met.

The arrival of the first aircraft had to be postponed.

The delay was a short one. By 31 May, the Seabees had completed nearly 4,000 feet of runway and about 1,000 feet of taxiway and the SATS field was prepared to accept its first aircraft. Colonel John D. Noble, Commanding Officer, MAG-12, who had established his CP at Chu Lai on 16 May, recalled that he ' 'caught a logistics flight from Da Nang to Cubi Point ... so I could bring the first flight of tactical aircraft to Chu Lai. June 1st dawned bright and clear, and at 0810, Colonel Noble led his four-plane division of Douglas A-4 Skyhawks from VMA-225 into Chu Lai. The other three pilots were Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Baker, commanding officer of VMA-225, and Majors Donald E. Gillum and David A. Teichmann. General McCutcheon, who was at Chu Lai for the landings, recalled, 'the NCOIC of the arresting gear cut off the tail of Noble's skivy shirt, a practice aboard carriers of the Fleet, carried over to our shore-based carrier ops.

Later in the day, on 1 June, four other A-4s from Lieutenant Colonel Bernard J. Stender's VMA-311 arrived at the field. The Chu Lai-based aircraft flew their first combat sorties that same day. At 1315, the four VMA-225 aircraft, with Lieutenant Colonel Baker in the lead, conducted air strikes in support of ARVN units six miles north of the field.

Although the field was operational, it was still unfinished and soil stabilization would continue to be a problem, espedally during the rainy season. Eventually the field had to be rebuilt. Lieutenant Colonel Baker observed:

... for a week or so before the rains came, this aluminum field was as flat and even as a pool table-the smoothest, bump-free surface I ever flew from. Later with rain cavitation the laterite was pumped up through the matting forming a slipping roller coaster effect.

But we flew! The Chu Lai operation used every capability my squadron had . . . We were trapped on landings, jato'd on takeoff. Refuelled by our GV's en route to our primary target. Loaded to the hilt with ordnance, we couldn't take off with much fuel. We did close air support ... in all weather and flew [radar controlled missions] all over the area in foul weather conditions day and night.

Major General Lewis W. Walt {left) relieves Major General William R. Collins (right) as Commanding General, III Marine Amphibious Force in an indoor ceremony at Da Nang on 4 June 1965. The ceremony was held indoors because the American colors were not permitted to be displayed outside. |

|

|

|

The SATS concept worked, but as Colonel Hardy Hay, the III MAF G-3, later remarked: '... no one will ever know what the [Chu Lai] project did to men and equipment unless they were there.

III MAF in Transition

The ID Marine Amphibious Force and its ground and air components experienced major changes of command within their first six weeks in Vietnam. Generals Collins and Fontana were near the end of their 13-month overseas tours and the Commandant, General Greene, appointed Brigadier General Lewis W. Walt, newly selected for promotion to major general, to replace Collins and Brigadier General Keith B. McCutcheon, also selected for promotion to major general, to be Fontana's replacement.** Walt looked the part of the football lineman that he was in

*General McCutcheon also told the story that General

Krulak had bet Major General Richard G. Stilwell, the MACV Chief of Staff, a case of scotch that a squadron would be operational within 30 days. General Krulak paid off the bet' 'on the basis that a full squadron was not operating there in the forecast time, only half of one.' McCutcheon, 'Marine Aviation in Vietnam,

**According to Colonel O'Connor, the 1st MAW chief of staff at the time, the question of who was to be CG III MAF was discussed several times. O'Connor recalled that 'General Fontana earnestly desired to have that assignment. He and General Collins were both nearing the ends of their overseas tours, and that General Collins would leave first. He talked to General Krulak about the matter several times ... He [Fontana] even volunteered to extend his overseas tour one year to take command of III MAF. General Krulak was very understanding, but explained that General Greene had already selected General Walt. This did not stop Fontana. He was senior to Walt, and stressed the doctrinal point that either an aviator or a ground officer could be in command . . . Finally he realized that the Commandant's decision would prevail . . . when he realized his time was limited in the Far East, he decided to take his last opportunity to command a wing in combat ... he would go to Da Nang to command the wing until he was forced to leave.' Col Thomas J. O'Connor, Comments on draft MS, dtd 27Nov76 (Vietnam Comment File).

|

Major General Walt speaks to troops of the 4th Marines at Chu Lai in June 1965. The new III MAF commander toured all three Marine bases shortly after taking command.

his college days. Upon promotion, he would be the junior major general in the Marine Corps and was one of the Corps' more decorated officers, two Navy Crosses and the Silver Star and combat service in both World War II and Korea. He had just completed a tour as the Director, Landing Force Development Center at Quantico.

In contrast to the physical bulk of Walt, McCutcheon was a short, slim man in appearance, but held equally imposing military credentials. Decorated with the Silver Star and Distinguished Flying Cross and a veteran of both World War II and Korea, McCutcheon was one of the pioneers in the development of close air support and helicopter tactics. In April 1965, he arrived in Japan as the 1st MAW assistant wing commander after completion of his duties as the CinCPac J-3. On 24 May, he assumed command of the wing's headquarters at Da Nang. Two weeks later, McCutcheon assumed command of the entire wing, upon General Fontana's departure for the United States.

After an informal promotion ceremony in the Commandant's office in Washington and a ceremonial battalion parade at Quantico, Major General Walt left for Vietnam at the end of May. On 5 June, he officially relieved General Collins as Commanding General, III MAF and Commanding General, 3d Marine Division.

During this period, there were other command changes. Upon his arrival, General McCutcheon also became Deputy Commander, III MAF, relieving General Carl, who then departed Vietnam as Commander, Task Force 79. On 12 June, General Carl, as assistant wing commander, assumed control of the wing's rear headquarters in Japan after General Fontana's departure. Six days later, General Karch returned to Vietnam as assistant division commander of the 3d Marine Division while Brigadier General Melvin D. Henderson assumed command of the 3d Marine Division (Rear) on Okinawa. These changes at the top were followed by rapid adjustments in staff assignments. The new layers of command contrasted sharply with the almost spartan simplicity of the old 9th MEB and could not help but cause some initial confusion. One former member of the 9th MEB staff, Major Ruel T. Scyphers, remembered:

Two full staffs arrived in Vietnam and superimposed authority over the brigade in a very short time. In this connection there wasn't a single moment of liaison or coordination between or among either staff. There was at one time 13 colonels roaming around headquarters without assignments or functions. With the limited space for billeting, messing, and working space-it was a nightmare.

Perhaps these growing pains were most dramatically reflected in the field of communications. During a visit to Vietnam in May, General Krulak remarked: ' 'I have never seen a worse situation than at Da Nang where a message which has immediate precedence has taken as long as 30 hours to get out of country, some incoming messages do not arrive at all. According to Colonel Hardy Hay, the IIIMAF G-3:

We were totally unprepared for the communication load that included an outrageous number of classified messages. Higher echelons simply did not have time to send letters by regular mail. Consequently, letters came by electronic means.

Colonel Nickerson, who had become the III MAF G-4, later explained that much of the message backlog was due to periodic power shortages ' 'with the down-time of generators" exceeding "uptime.' ' He commented that the number of classified "dispatches that had not been encrypted or decrypted often exceeded 5,000'' and that ' 'manual processing was tedious." Nickerson also remarked on the fact that "higher, comfortable, well-staffed headquarters were firing questions or assigning responsibilities at a prolific rate . .. . Colonel Nickerson praised the efforts and ingenuity of Colonel Frederick C. Dodson, the III MAF communications officer, and the communications section for reducing the backlog to manageable proportions. Finally Nickerson observed:

Reading, analyzing, answering, dodging, eliminating these dispatches was a tremendous load. Colonel Regan Fuller, MAF Chief of Staff, challenged, cajoled, and led the staff in his cantankerous manner on a crippling schedule in order to catch up. ... After many weeks he was successful and he accomplished all of this while ill with a bleeding ulcer.

|

|

Communications was only one of the trouble areas caused by the transformation of the command. The troops sent into Vietnam had to be supplied and maintained, and MACV had planned to establish a Da Nang Support Command under the Army's 1st Logistic Command to provide common item supply for III MAF. At the Honolulu Conference in April, this plan was modified and Admiral Sharp directed that the Commanding General, III MAF, in his capacity as Naval Component Commander, would assume the responsibility for common item supply from Marine and Navy sources, as well as the operation of the ports in I Corps. Since the Navy had not yet established a support activity in Vietnam to run the ports, the job had to be done by Marine Corps personnel and equipment. This placed a heavy burden on III MAF.

Following the Chu Lai landings, Colonel Nickerson, the III MAF G-4, held nightly meetings "as the hectic problems spanned the logistic spectrum." These meetings were "designed for liquidating problems, coordinating efforts and insuring that all had the necessary information to do their jobs. On 16 May, Nickerson presented a logistic support concept for the Marine command. While assuming that the Navy would eventually establish a support activity, the concept directed the III MAF to run the ports and at the same time make

*Colonel Rex C. Denny, from the III MAF G-3 Section, recalled that the fact that General Walt was both the 3d Marine Division and III MAF commander "caused some humorous and often confusing staff work. MAF staff and division staff working on same project or MAF staff doing work division staff rightly should." Col Rex C. Denny, Comments on draft MS, dtd 10Nov76 (Vietnam Comment File). Lieutenant General Leo J. Dulacki, who in 1965 was the III MAF G-2, remarked that "when III MAF was deployed to RVN, it was assumed that the Hqs would be a skeleton Hqs, dependent on the Wing and Division Hqs for substantial personnel support and, in/act, for many of the operational functions." Dulacki pointed out that this concept of organization, which had been accepted as standard for years, was for the first time "put to the test." He noted that the subsequent, "necessary, but agonizingly slow, growth of the III MAF headquarters in order to perform its tasks would indicate that this concept lacks vitality especially in a commitment of forces of long duration." LtGen Leo J. Dulacki, Comments on draft MS, dtd 240ct76 and [Jul] 77 (Vietnam Comment File)

|

Marines from the 2d Battalion, 3d Marines cross the Cu De River in amphibian tractors. The troops later evacuated villagers/row the hamlet ofPho Nam Thuong to Le My.

distribution of its supplies through its own force logistic support group (FLSG).

The III MAF FLSG, commanded by Colonel Mauro J. Padalino, was built around the nucleus of the 3d Service Battalion from the 3d Marine Division and reinforced by support elements from the 3d Force Service Regiment on Okinawa. Colonel Padalino, a veteran supply officer who had served in both World War n and Korea, maintained his headquarters at Da Nang while two force logistic support units, FLSU-1 and -2, serviced Chu Lai and Phu Bai. Despite shortages compounded by breakdowns in equipment and a complex peacetime supply system, the FLSG managed to meet the most urgent requirements of the fully operational MAF.* The logistic situation gradually improved after the Defense Department permitted the Commandant of the Marine Corps to release the emergency FMFPac mount-out supplies for shipment to Vietnam on 5 June.

In spite of the logistic strain, more than 9,000 personnel had been added to the Marine force in Vietnam by mid-June. They were spread over an area of 130 square miles and engaged in a wide variety of tactical, support, and combat support activities. Both the 3d Marines and the 4th Marines

|

Marines from the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines cross a stream in the northern sector of the Chu Lai TAOR, The Marine in the foreground appears to be able to smile despite a cigarette in his mouth and water up to his neck.

had established their command posts in Vietnam. Elements of the 12th Marines, the division artillery regiment, were located at all three enclaves. The 1st Battalion, 12th Marines under Major Gilbert W. Ferguson supported both Da Nang and Phu Bai, while Lieutenant Colonel Arthur B. Slack, Jr.'s 3d Battalion, 12th Marines provided artillery support for the 4th Marines at Chu Lai. Other supporting units, spread throughout the three enclaves, included major elements of the 3d Motor Transport Battalion, the 3d Engineer Battalion, and the 3d Reconnaissance Battalion. The wing consisted of two aircraft gioups, MAGs-12 and -16 with five helicopter squadrons, an equal number of fixed-wing squadrons, and ancillary ground components.

Upon taking command, General Walt had toured the three base areas and familiarized himself with each. Based upon his own observations, supported by available intelligence, he concluded that the VC were building up their forces in the areas contiguous to the Marine enclaves. Walt decided that the Marines had to extend their TAORs and at the same time conduct deeper and more aggressive patrolling. Colonel Hardy Hay, the III MAF G-3, recalled that shortly after Walt's arrival:

He asked me one night, 'What is our major G-3 problem?' My answer-We have got to convince Saigon that by trying to establish a ring around Chu Lai, Da Nang, and Phu Bai-we will never have enough men and material to adequately do it.

Yet as Hay observed, the Marines were unable to undertake offensive operations because their ''hands were tied by ComUSMACV directives.'

On 15 June a significant change in the role for the Marines took place when General Westmoreland permitted General Walt to begin search and destroy operations in the general area of his enclaves, provided that these operations contributed to the defense of the bases. The MACV commander further directed that the Marines at Chu Lai conduct operations to the west of their TAOR into the suspected Do Xa VC supply complex.

With this new authority and with the concurrence of General Thi, the I Corps commander, General Walt enlarged the TAORs at all three enclaves. The enlargements gave the units of the division more room for offensive operations and provided distinguishable lines of demarcation on the ground since the trace of the new TAORs followed natural terrain features. At Da Nang, the area occupied by the 3d Marines consisted of 172 square miles and contained a civilian population of over 50,000 persons, but the populated region directly to the south and east of the base still remained the responsibility of General Thi's forces. Within the new Chu Lai TAOR of 104 square miles, there were 11 villages, containing 68 hamlets, and a dvilian population of over 50,000. The area of responsibility for the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines at Phu Bai was much smaller, consisting of 61 square miles, but within that area dvilian population numbered almost 18,000.

The Seeds of Pacification

Shortly after General Walt assumed command of ID MAF he had a survey made which revealed that over 150,000 civilians were living within 81mm mortar range of the airfield, and consequently, the 'Marines were into the pacification business.'36 In fact, General Greene later observed:

From the very first, even before the first Marine battalion landed in Da Nang, my feeling, a very strong one which I voiced to the Joint Chiefs, was that the real target in Vietnam were not the VC and the North Vietnamese, but the Vietnamese people . . .

Other than the Le My experiment, in June 1965 Marine pacification consisted largely of an embryonic civic action program which had begun a few months earlier as an offshoot of the former Marine task element's "people to people" medical assistance program. In April, the civil affairs officer of the 3d Marines, 1st Lieutenant William F. B. Francis, in cooperation with local officials, established a dispensary in the village of Hoa Phat, known to the Marines as Dog Patch, on the western perimeter of the Da Nang Airbase. A Vietnamese nurse ran the facility, while a Navy hospital corpsman and a lab technician paid occasional visits. Lieutenant Francis begged and borrowed medicines from various U.S. agencies, both military and civilian.

Medical assistance programs of this type expanded throughout the Marine TAORs. Lieutenant Colonel Cement's battalion at Le My established another dispensary and opened sick call to the civilian population every other day, while the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines did the same in its area of operations. The artillery battalion at Chu Lai, the 3d Battalion, 12th Marines, in conjunction with Company B, 3d Medical Battalion, provided daily dispensary service for the local populace. The 3d Battalion, 4th Marines at Phu Bai established a weekly medical service in three small hamlets nearby. In all three Marine enclaves, hospital corpsmen accompanied Marine patrols into the local villages where they dispensed soap and treated minor illnesses.

Civic action, even at this very early stage in its development, encompassed more than merely dispensing medicine. At Chu Lai, the 400 people who were displaced by the airfield were resettled in a new area with the assistance of the 4th Marines and the local district government. The need of much of the rural population for food, clothing, and shelter was apparent to all. The Marines could not hope to eliminate all of the suffering, but they could furnish some assistance. They made contact with private charitable organizations, such as CARE and the Catholic Relief Society, and were able to obtain over 10,000 pounds of miscellaneous supplies to be distributed within their TAORs. The Marines discovered other means besides charity for making life more pleasant for the villagers. In one instance the 3d Marine Division band, marching through Hoa Phat, suddenly struck up a gay tune, and then, to the delight of hundreds of Vietnamese who had gathered, the band played an impromptu concert for over an hour.

There was a need for overall guidance and direction since civic action was too important to leave to the good will and natural enthusiasm of individual Marines. On 7 June, III MAF published an order which established civic action policy. Major Charles J. Keever, the III MAF Civil Affairs Officer who prepared the directive, had visited hamlets around both Da Nang and Chu Lai to obtain the details of the home life of the Vietnamese villagers, as well as the dvic action programs conducted by the Marines. In the order he defined civic action as the ' 'term applied to the employment of the military forces of a nation in economic and social activities which are beneficial to the population as a whole."38 On 14 June, General Walt held a meeting with 25 of his senior officers and reiterated III MAF civic action policies. The goal was to stabilize the political situation and to build up the government by providing it with the respect and loyalty of its citizens.

The Marines attained their first measurable success in the struggle for the people when villagers in two hamlets, five and a half miles northwest of Le My, elected to move into an area under Marine protection. Lieutenant Colonel Clement's battalion had conducted several sweeps along both banks of the Song Cu De, up river from Le My. According to Clement:

The movement of the people from these two hamlets, of Pho Nam Thuong and Nam Yen, was very important to me because I did not want to extend my defensive posture to include Pho Nam, yet I did not want the VC to have those people. The people were hesitant to move-reluctant to give up their homes; apprehensive about the rice harvest to come; and fearful that association with government forces would mark them for retaliation by the VC.

Clement then decided to convince the villagers that their hamlets were in a combat zone and that "they would be safer to accept refugee status and relocate near Le My . . . ." The battalion commander, several years later, recalled:

I directed that H&I [harrassing and interdiction] fires be brought close in to the hamlet, night after night. The attitude of the people about relocation "improved" in time and the relocation operation was scheduled . . . not only did I have to "convince" the people of Pho Nam and [Nam Yen] to relocate, but I had to convince the Vietnamese authorities of the necessity of this move since the official policy was to discourage refugees.

On 15 June, Lieutenant Colonel Clement drew up plans for a three-company action in conjunction with the ARVN and Popular Forces. Three days later, the Marine battalion and Vietnamese forces moved through the hamlets and brought out more than 350 villagers, who then moved into the Le My complex. Clement later admitted, "I suppose given a free choice, the people would not have left their hamlet. I influenced their decision by honesty, sincerity, and a hell of a lot of H&I fires.

By this time, Le My had become a show case for pacification. Lieutenant Colonel Clement explained:

... by virture of their success and notoriety, the Marines at Le My . . . were not maneuvered around. . . . This permitted the battalion to conduct a coun-terinsurgency campaign based upon the situation as it appeared to the people on the ground. This privileged position permitted a great deal of person-to-person confidence to develop, and, along with it, a personal commitment to the government cause.

June Operations in the Three Enclaves

With the enlarged TAORs and broader mission in June, General Walt based his concept of operations on the establishment of an elaborate defensive network for the base areas together with forward outposts and extended patrolling in the outlying areas. He envisioned ' 'the creation of a series of dug-in timbered mutually-supporting defensive positions into which infantry units may withdraw in the event of heavy enemy attack" as the main defensive line for each enclave. Some 3,000 to 5,000 meters forward of this line, Walt wanted the establishment of a ' 'lightly fortified combat outpost line" for a more mobile defense. Concurrently, the III MAF commander ordered all units to continue ' 'aggressive patrolling" in all TAORS "as a means of keeping the enemy off balance, forcing him to deploy, and giving early warning of any attempts to concentrate along TAOR boundaries.

At Da Nang, the resulting expanded operations resulted in increasing contacts with enemy small units. The 3d Marine Division for the month reported:

10 June. In the western sector of the Da Nang TAOR, a company patrol uncovered a VC base camp capable of supporting 150 people. The camp was destroyed ....

21 June. During the morning, 2 reinforced squads from 2/3 were attacked while on patrol in the Da Nang TAOR by an estimated 8 VC, using small arms and grenades. One Marine was KIA and 3 WIA, while the VC lost 4 KIA and 2 women captured ....

22 June. In a brief fire fight at an outpost manned by Company C, 1/3, in the southern portion of the Da Nang enclave, two VC were killed with no Marine casualties.

24 June. Elements of 1/9, under operational control of 3d Marines, and the 1st Bn, 4th ARVN Regiment conducted a combined sweep and clear operation south of Da Nang Air Base along the Song Cau Do ... 1/9 apprehended 19 suspected VC and the ARVN 1/4 had killed 2 VC. There were no Marine casualties.

The 4th Marines at Chu Lai was equally busy. Lieutenant Colonel Fisher's 2d Battalion, 4th Marines provided security for the Seabees while they constructed the airfield. Shotgun riders from one rifle company were assigned to every vehicle day and night. Two of Fisher's other rifle companies and his headquarters and service company manned the main defensive line, while his fourth rifle company manned forward outposts and conducted patrols. The other infantry battalions at Chu Lai, the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines and the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, made similar dispositions.

With the consolidation of the Chu Lai base area, Colonel Dupras gradually extended the 4th Marines TAOR so that the air facility was out of range of enemy mortars and light artillery. Lieutenant Colonel Fredericks, the commanding officer of the 1st Battalion, 4th Marines, recalled that initially the Marines had to operate in a very restricted zone and that the enemy was aware of this restriction. With a combination of extended patrolling and civic action within the villages in the TAOR, by the end of June Colonel Dupras was confident that his troops had eliminated the ability of the Viet Cong to mass and attack the airfield. Enemy action was limited to small probes against outposts, sniping, and occasional hand grenade incidents. At the end of the month, the 4th Marines and its supporting units had killed 147 VC while suffering four dead and 23 wounded.

In the Marines' northernmost enclave at Phu Bai, the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines faced a large challenge. General Krulak commented that although the unit was operating aggressively throughout its TAOR, it was too much to expect the base to be safe from enemy mortar attack. He believed that the Marines would require two more battalions and probably a regiment to defend the base properly. The low rolling hills and swampy gullies in the area were divided just to the right of center of the TAOR by a prominent north-south ridgeline dominated at the north end by Hill 180. More disturbing was the fact.

|

Marines from the 3d Battalion, 4th Marines take cover near Phu Bai. Their patrol had just been fired upon by the VC.

that the area directly to the north and east of the airstrip, designated Zone A, was not included in the Marine area of responsibility.

Lieutenant Colonel William W. 'Woody' Taylor,* the battalion commander, was unhappy with the tactical arrangements and commented that the VC could apparently come in and shoot up the villages with impunity while the Marines were not permitted to operate in Zone A.47 On 21 June, General Nguyen Van Chuan, the 1st ARVN division commander, incorporated the sector into the Phu Bai TAOR, and at the same time gave Lieutenant Colonel Taylor limited operational control of the five South Vietnamese Popular Force platoons in Zone A. This eventually led to the development of the highly successful Marine and South Vietnamese combined action company. (See Chapter 9)

By the end of June, the stepped-up activity in all three Marine enclaves had placed a heavy strain on III MAF, in terms of both men and material. During the month, General Walt requested the remaining battalions of the 3d Marine Division on Okinawa.** It was now obvious in both Saigon and Washington that more American forces were needed and the entire subject of the total U.S. troop commitment to the war in Vietnam was undergoing reconsideration.

* LtCol Taylor relieved LtCol Jones when the latter suffered a heart attack on 28 April 1965.

**0n 11 June, 1/9 arrived and relieved 3/9, which returned to Okinawa for transfer back to the United States. This exchange of units was in line with the peacetime battalion transplacement system then in effect and could not in any sense be considered a reinforcement.

|

NAVAL COMMUNICATIONS SYSTEM

_____________________________________________________________________________

Drafted by Sec/Code Ext. Nr. Released by

MRS. WHITE DL 42504 W. J. VAN RYZIN

_____________________________________________________________________________

FROM: CMC

261139Z/47 (MAY 1970)

TO: ALMAR

UNCLAS //NO1650//

MCBUL 1650. REPUBLIC OF VIETNAM ARMED FORCES MERITORIOUS UNIT CITATION OF THE GALLANTRY CROSS WITH PALM; CASE OF THE III MARINE AMPHIBIOUS FORCE

1. THE SECRETARY OF THE NAVY HAS APPROVED THE ACCEPTANCE OF THE SUBJECT AWARD FOR THE III AMPHIBIOUS FORCE TO INCLUDE ALL NAVY, MARINE CORPS AND COAST GUARD UNITS ATTACHED TO OR SERVING THEREWITH DURING THE PERIOD 8 MARCH 1965 THROUGH 20 SEPTEMBER 1969

2. THE BUREAU OF NAVAL PERSONNEL, NAVY DEPARTMENT WILL PROMULGATE THIS AWARD IN THE VERY NEAR FUTURE LISTING ALL UNITS OF THE NAVY, MARINE CORPS AND COAST GUARD ENTITLED TO THE AWARD INCLUDING THEIR DATES OF PARTICIPATION

3. SECNAV ALSO APPROVED THE ASSEPTANCE OF THSI AWARD FOR ARMY AND AIR FORCE UNITS ATTACHED TO AND SERVING WITH III MAF DUREING THE PERIOD IN QUESTION. BY SEPARATE CORRESPONDENCE SECNAV REQUESTED THE DEPTS OF THE ARMY AND AIR FORCE TO PROMULGATE THE AWARD TO ARMY AND AIR FORCE UNITS ENTITLED THERETO

4. ALTHOUGH INDIVIDUAL UNIT AWARDS WERE ALSO PRESENTED IN THE FIELD TO THE BELOW-LISTED UNITS, TO PRECLUDE DUPLICATION OF AWARDS, SECNAV APPROVED ACCEPTANCE OF ONLY THE III MARINE AMPHIBIOUS FORCE AWARD. THESE AWARDS WILL BE RETAINED AT HEADQUARTERS MARINE CORPS WITH NO FURTHER ACTION TAKEN

3D BATTALION, 4TH MARINES 15JUL-3AUG66

1ST MARINE DIVISION APR66-MAY69

3D MARINE DIVISION MAR65-JAN69

9TH MARINE REGIMENT JAN-DEC68

4TH MARINE REGIMENT JUL-OCT66

III MARINE AMPHIBIOUS FORCE 1JAN-15DEC68

(CANCELED)

5. ALL MARINE CORPOS UNITS UNDER THE OPERATIONAL CONTROL OF THE III MARINE AMPHIBIOUS FORCE DURING THIS PERIOD ARE ENTITLED TO THIS AWARD AND AS SUCH ARE CONSIDERED CITED UNITS WITHIN THEMSELVES AND ALL SUCH UNITS WHICH ARE AUTHORIZED FLAGS ARE ENTITLED TO FLY THE STREAMER OF THE GALLANTRY CROSS WITH PALM

6. ALL PERSONNEL OF THE ABOVE-MENTIONED UNITES DURING THE PERIOD IN QUESTION WHO WERE PRESENT AND SERVING IN VIETNAM ARE AUTHORIZED TO WEAR THE GALLANTRY CROSS RIBBON BAR WITH PALM AND FRAME. COMMANDING OFFICERS WILL DETERMINE ELIGIBILITY FROM ENTRIES IN SRB'S AND OQR'S, AUTHORIZED THE WEARING OF THE RIBBON AND ENTER SUCH AUTHORITY IN SRB'S OF ENLISTED MEN AND IN THE CASE OF OFFICERS, FORWARD A COPY OF THE AUTHORIZING LETTER TO CMC (CODE DGH) FOR FILE ON THEIR OFFICIAL RECORD. WHERE RECORDS ARE NOT AVAILABLE TO MAKE DETERMINATIONS FROM, APPLICATIONS SHOULD BE SENT TO THE COMMANDANT OF THE MARINE CORPS (CODE DL)

7. THE RIBBON BAR WILL NOT BE ISSUED BY THIS HQ, BUT MAY BE PURCHASED AT MARINE CORPS EXCHANGES AND MILITARY SHOPS

8. EXTENSIONS OF TOURS OR AN ADDITIONAL TOUR WITH ONE OR MORE UNITS ENTITLED TO THIS AWARD WILL NOT CONSTITUTE A BASIS FOR A SECOND AWARD OF THE SUBJECT CITATION; NOR IS A DEVICE AUTHORIZED FOR A FUTURE/ADDITIONAL AWARD OF THIS DECORATION

9. THIS BULLETIN IS APPLICABLE TO THE MARINE CORPS RESERVE

10. THIS BULLETIN IS CANCELED ON 30 NOVEMBER 1970.

|

III Marine Expeditionary Force

| III Marine Expeditionary Force |

III MEF insignia |

| Active |

October 1, 1942 - June 10, 1946

May 7, 1965 - present |

| Country |

United States |

| Branch |

USMC |

| Type |

Marine Air-Ground Task Force |

| Role |

Expeditionary combat forces |

| Size |

17,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Commanders |

Current

commander |

LtGen Terry G. Robling |

The III Marine Expeditionary Force is a Marine Air-Ground Task Force of the United States Marine Corps that is forward-deployed and able to deploy rapidly and conduct operations across the spectrum from humanitarian assistance and disaster relief to amphibious assault and high intensity combat. III MEF maintains a forward presence in Japan and Asia to support the U.S. – Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security and other alliance relationships of the United States. III MEF also conducts combined operations and training throughout the region in support of the National Security Strategy for Theater Security Cooperation.

Mission

III Marine Expeditionary Force, as the Marine Corps’ forward-deployed Air-Ground-Logistics-Base Team, is a force in readiness able to deploy rapidly by any and all means and conduct operations from Special Purpose MAGTF through MEU, MEB and MEF, across the spectrum from humanitarian assistance and disaster relief to amphibious assault and High Intensity Combat. III MEF maintains a forward presence in Japan and Asia to support the U.S. – Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security and our other alliance relationships. III MEF conducts combined operations and training throughout the region in support of our National Security Strategy for Theater Security Cooperation.

History

The old III MAF insignia.

The III Marine Expeditionary Force is a descendant of the I and III Marine Amphibious Corps, activated during World War II.

World War II

The III Amphibious Corps was originally activated as the I Marine Amphibious Corps on 1 October 1942. Consisting of the 3rd Marine Division, the 37th Infantry Division of the United States Army, and a brigade of the 3rd New Zealand Division, it conducted the invasion of Bougainville. It was renamed the III Amphibious Corps on 15 April 1944 and as such took part in fighting against the Japanese Empire in the Pacific theater during World War II. It fought in some of the bloodiest battles, including the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign and Okinawa. Following the termination of hostilities, it occupied northern China, where it was deactivated on 10 June 1946.

Vietnam War

The force was reactivated to serve in the Vietnam War in 1965. From 1966 to 1970, III MEF was renamed III Marine Amphibious Corps (III MAF) and consisted of the 1st Marine Division, 3rd Marine Division and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. The MAF's area of operations was in the northern I Corps Tactical Zone. Redeployed to a permanent forward base on Okinawa in 1988, the III Marine Expeditionary Force helps to fulfill the 1952 United States treaty obligation to defend Japan.

Post-Cold-War Period

Since the end of the Cold War, III MEF has served in 1990 Operation Desert Shield to help protect Saudi Arabia. More recently the Marines have also engaged in humanitarian work, such as evacuating civilians in the Philippines following the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991, and providing disaster relief in the Japanese city of Kobe following a devastating earthquake in January 1995.

More recently III MEF elements provided the headquarters of Joint Task Force 536, later redesignated Combined Support Force 536, which was established at U-Tapao Royal Thai Navy Airfield in Thailand in the aftermath of the the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, the 'Asian Tsunami.

Structure

|

THE MARINE WAR: III MAF IN VIETNAM, 1965-1971

by Jack Shulimson, U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center

In this paper, I will try to describe the role of the Marine Corps in Vietnam from the perspective of its main combat component in the war, the III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF). While my interpretation is my own, these remarks are based largely upon the Marine Corps official volumes of the war.

Prior to 1965, contingency plans for Southeast Asia called for the insertion of Marines in the event of an attack on South Vietnam. After the Gulf of Tonkin crisis in August 1964, U.S. commanders activated the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade (9th MEB).

By early 1965, sensing victory nearly in their grasp, the Communists directed attacks against U.S. advisors. In February 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered a series of retaliatory American air strikes against North Vietnam.

As the air war escalated, on 22 February 1965, U.S. Army General William C. Westmoreland, Commander, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (ComUSMACV), asked for two U.S. Marine battalions to protect the Da Nang base in South Vietnam's I Corps. By the end of the month, the Johnson administration agreed to the request. Finally, on 7 March 1965, the U.S. Joint Chiefs sent the long awaited signal to land the MEB.

The following day, 8 March, the first wave of Marine Battalion Landing Team (BLT) 3/9 at Da Nang. On the beach waiting for the Marines was a host of welcoming South Vietnamese dignitaries and local schoolgirls who bedecked the 9th MEB commander, Brigadier General Frederick J. Karch, with a garland of flowers. Indeed one of the famous newsphotographs of the war shows a dour General Karch with a lei around his neck. Karch later stated "When you have a son in Vietnam and he gets killed, you don't want a smiling general with flowers around his neck . . . ." By the end of March 1965, the 9th MEB numbered nearly 5,000 Marines at Da Nang, including two infantry battalions, two helicopter squadrons, and supporting units.

Notwithstanding the Marine buildup, the U.S. involvement in Vietnam remained limited. According to the landing directive: "The U.S. Marine force will not, repeat will not, engage in day to day actions against the Viet Cong."

These constrictive conditions lasted for only a brief period. In April, the President agreed to reinforce and to permit the Marines to engage Communist insurgents. By early May 1965, the Marines had established two additional enclaves, one in Chu Lai, 57 miles south of, and at Phu Bai, 30 miles north of Da Nang.

By this time, the 9th MEB had become the III Marine Amphibious Force (III MAF). It consisted of both the 3d Marine Division and the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing (MAW). In midsummer 1965, in discussions with General Westmoreland, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara agreed to deploy additional U.S. troops both Marine and Army to South Vietnam. In August 1965, the first elements of the 1st Marine Division arrived at Chu Lai eventually followed by the division headquarters.

As the war expanded, command arrangements, like the American commitment, evolved over time without any master plan. Still by the end of 1965, the United States had established the outlines of the complex command structure which, with minor modifications, it would fight the remainder of the war. III MAF headed since June by Major General Lewis W. Walt reported to USMACV (Westmoreland). General Westmoreland exercised this authority through the U.S. chain of command. Formally MACV was a unified command directly subordinate to the

U.S. Pacific Command under Admiral Ulysses S. Grant Sharp in Hawaii, but Washington often "cut out Sharp.

De facto functional and geographic divisions characterized the employment of the U.S. Armed Forces in Vietnam. The Navy conducted the maritime anti-infiltration Market Time operations, and shared the air campaign against North Vietnam with the Air Force. Two U.S. Army Field Forces, Vietnam, under MACV, were responsible for the American ground war in South Vietnam except for I Corps. In I Corps, often referred to as "Marine land," III MAF had authority over all U.S. ground tactical units there. The commander of the U.S. Air Force Second Air Division, later the Seventh Air Force, as Westmoreland's Deputy for Air, coordinated the U.S. air war in South Vietnam and provided air support to U.S. Army and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces.

The relationship between III MAF and the U.S. Air Force component command in South Vietnam was more complex. When in March 1965, General Westmoreland informed CinCPac that he planned to place Marine fixed-wing units under the overall operational control of his Air Force component commander, Admiral Sharp overruled him. In no uncertain terms, in a message probably drafted for him by Marine Brigadier General Keith B. McCutcheon, who later became CG 1st MAW, Sharp told Westmoreland that he would exercise operational control of Marine aviation through III MAF.

While III MAF was under the operational control of MACV, General Walt also reported directly through Marine channels to the Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, Lieutenant General Victor H. ``Brute'' Krulak for administrative and logistic support. While not in the operational chain of command, General Krulak was not one to deny General Walt the benefit of his advice. Through the same Marine channels, Krulak was responsible to The Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Wallace M. Greene, Jr., in Washington, who also had his perceptions on the conduct of the war.

From the Marine perspective, in Vietnam and in both Hawaii and Washington, the III MAF location in the densely populated rice- bowl area south of Da Nang necessitated a pacification strategy.

On the other hand, General Westmoreland contended that the introduction of North Vietnamese units into the south created a new situation and wanted the Marines to engage them. He had doubts about the thrust of the Marine pacification campaign. According to a MACV analysis, the Marines were "stalled a short distance south of Da Nang," because the ARVN was unable to "fill in behind the Marines in their expanding enclaves." On the other hand, Westmoreland stated that he, "had no desire to deal so abruptly with General Walt . . . [to] precipitate an interservice imbroglio.

General Walt also wanted to avoid any confrontation. His basic position was that he would engage the enemy's main force units, but first he wanted "to have good intelligence.

Both Generals Krulak in Hawaii and General Greene in Washington supported General Walt. They voiced their concerns directly to General Westmoreland and through the command channels open to them. Although differing in minor details, the two Marine generals in essence advocated increased pressure upon North Vietnam and basically an "ink blot" strategy in South Vietnam, combining civic and military efforts. Generals Greene and Krulak would engage the Communist regulars for the most part only "when a clear opportunity exists to engage the VC Main Force or North Vietnamese units on terms favorable to ourselves.

While the two Marine generals received a hearing of their views, they enjoyed little success in influencing the MACV strategy or overall U.S policy toward North Vietnam. According to Krulak, Secretary McNamara personally told him that the "ink blot" theory was "a good idea but too slow.

Despite the differences over pacification and the big unit war between MACV and the Marines, General Westmoreland's directives were broad enough to include both approaches and in a sense paper over the real distinctions between the two. The Marines were to defend and secure their base areas; to conduct search and destroy missions against VC forces that posed an immediate threat and against distant enemy bases; to conduct clearing operations in contiguous areas; and finally, to execute contingency plans anywhere in Vietnam as directed by ComUSMACV.

Working within these "all-encompassing" objectives, General Walt developed what he called his "balanced strategy." This consisted of a three-pronged effort employing search and destroy, counter-guerrilla and pacification operations. An integral part of his concept was the Combined Action program, in which III MAF assigned a squad of Marines to a Vietnamese Popular Forces platoon. The premise was that this integration of the Vietnamese militia with the Marines would create a bond of mutual interest between the Americans and local populace. Walt's initial plan called for III MAF to secure the entire I Corps coastal plain by the end of 1966, once it joined its two largest enclaves, Da Nang and Chu Lai.

This soon proved too optimistic. In the Spring of 1966, an unforeseen internal South Vietnamese political crisis threw the situation in I Corps into chaos. Through a combination of tact and firmness, General Walt managed to keep Marine forces uninvolved. For the Marines, however, their pacification effort south of Da Nang had come to a complete standstill.

Further in July, the North Vietnamese mounted their first offensive into South Vietnam directly through the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). In response, the 3d Marine Division deployed north to counter. General Westmoreland, moreover, feared that the North Vietnamese might circumvent the Marine defenses and attempt to open a corridor in the western border area, near the Special Forces base at Khe Sanh. III MAF reluctantly, at the suggestion of Westmoreland, sent a battalion to Khe Sanh "just to retain that little prestige of doing it on your own volition rather than doing it with a shoe in your tail.

By the end of 1966, the two Marine divisions of III MAF were fighting two separate wars. In the north, the 3d Marine Division fought a more or less conventional campaign while the 1st Marine Division took over the counter-guerrilla operations in the populous south. Although by December 1966, III MAF numbered nearly 70,000 troops, one Marine general summed up the year's frustrations, " . . . too much real estate--do not have enough troops.

A proposed anti-infiltration barrier to be established just south of the DMZ caused further difficulties. Although credited to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, the concept of a defensive ``barrier'' had many authors. It received only serious consideration in the Spring of 1966 when McNamara raised the question with the Joint Chiefs. In August, a special study group of scientists reported that a unmanned air-supported barrier could be established in a year's time.

Despite serious objections by other senior commanders, General Westmoreland was not all that opposed to the barrier. Despite doubts about an unmanned barrier, he himself, was thinking of building a manned ``strong point obstacle system." He saw the proposal as an opportunity to institute his own concept.

The Marine command would be at the center of the project. Very early, General Walt made known his unhappiness, contending that a barrier defense ``should free Marine forces for operations elsewhere not freeze such forces in a barrier watching defensive role.

Having little choice, in April 1967, the 3d Marine Division began the erection of the strong point obstacle system (SPOS) along the DMZ. This was dubbed the ``McNamara Line,'' but just as easily could have been called the "Westmoreland line.

Forced to fill the gap left in southern I Corps, in April as well, General Westmoreland reinforced the Marines with the Army's Task Force Oregon, later to become the Americal Division. The MACV commander also had requested an increase in his overall strength, planning to reinforce the Marines with at least two Army divisions. Fearful that these new numbers would necessitate a callup of the Reserves, Washington in the summer of 1967 cut Westmoreland's request nearly in half.

With this northward deployment of Marine forces, northern I Corps became the focus of Marine concern with little prospect of relief. In April, the Marines had fought an extremely bloody battle with North Vietnamese regulars for the hills overlooking Khe Sanh. While there would be a lull in that sector, the North Vietnamese in the following months would place continuing pressure upon the 3d Marine Division's fixed positions.

At about this time, the North Vietnamese Politbureau called for ``a decisive blow'' to ``force the U.S. to accept military defeat. In the fall of 1967, the Communist forces launched the first phase of their campaign. In a reverse of their usual tactics, the North Vietnamese mounted mass assaults lasting over a period of several days. During late September and early October, the Marine outpost at Con Thien in the eastern DMZ sector came under both infantry attack and artillery bombardment. While repulsed at Con Thien, the NVA continued their offensive through November in South Vietnam's II and III Corps.

In the DMZ sector, construction of the Strong Point system under went modification. The 3d Marine Division had made limited progress. Faced with mounting casualties in November, General Westmoreland approved a major change to his original plans. In essence, the division was to halt all construction until ``after the tactical situation had stabilized.'' While some work on strong points continued, the situation never stabilized.

Much evidence indicated that the enemy was on the move. Captured enemy documents spoke of major offensives throughout South Vietnam. One in particular mentioned a general offensive and general uprising and directed the coordination of military attacks ``with the uprisings of the local population to take over towns and cities.''(27)

General Westmoreland, nevertheless, believed the enemy's more logical targets to be the DMZ and Khe Sanh. He thought the Communist objectives to be the seizure of the two northern provinces of South Vietnam and to make Khe Sanh the American Dien Bien Phu.

With the Marines strung out along the DMZ in the north, Westmoreland deployed the 1st Air Cavalry Division to I Corps. In mid-January 1968, III MAF was in actuality a small field army, consisting of what amounted to two Army divisions, two reinforced Marine Divisions, a Marine aircraft wing, and supporting forces, numbering well over 100,000.

As General Westmoreland reinforced III MAF in mid-January 1968, he began to have misgivings. General Westmoreland believed that Marine Lieutenant General Robert E. Cushman, Jr., who had relieved General Walt, was "unduly complacent. Westmoreland worried about what he perceived as the Marine command's ``lack of followup in supervision,'' its employment of helicopters, and its generalship.

In mid-January 1968, the MACV commander decided to establish a new forward headquarters to control the war in the northern two provinces under his deputy, General Creighton W. Abrams. Although both General Cushman at Da Nang and General Krulak in Hawaii had their suspicions about Westmoreland's motivations, the two outwardly acknowledged the validity of the MACV commander to have his forward headquarters where, he believed the decisive battle of the war was about to begin.

On 20 January, the North Vietnamese had attacked the Khe Sanh hill outposts and subjected the main base to both ground and artillery assaults the following day. They, however, had neither the capability nor possibly the intention to mount a full out attack. Instead, the Communist forces launched over the Tet holidays an offensive unparalleled in the Vietnam War in its sweep and intensity. From 29-31 January, the Communist forces struck through the length and breadth of South Vietnam-- everywhere that is except at Khe Sanh.

In I Corps, the enemy hit all of the major population centers including Da Nang and Hue. U.S. and Vietnamese troops successfully repulsed all of these attacks except at Hue. It took 26 days of fierce, determined, house-to-house fighting for U.S. Marines and soldiers as well as ARVN troops to rid the city of the invaders.

At Da Nang, the delicate issue over command relations once more arose complicated by events near Khe Sanh. While the 1st Marine Division at Da Nang during Tet had thrown back with heavy losses the first enemy assaults, on 5-6 February, North Vietnamese battalions from the 2d NVA Division had penetrated the Da Nang perimeter. At the same time, North Vietnamese troops overran the Special Forces Camp at Lang Vei, south of Khe Sanh.

These two events led to a strange confrontation with General Westmoreland. Believing that III MAF should have relieved Lang Vei, General Westmoreland called a special meeting on 7 February, where he became even more upset as he learned about the situation at Da Nang.

Apparently, however, General Cushman was unaware of Westmoreland's unhappiness. His view was that the purpose of the meeting was to obtain Westmoreland's approval for the reinforcement of Da Nang. In any event the Marines at Da Nang received the reinforcements. As far as Lang Vei, Cushman later related that he was "criticized because I didn't send the whole outfit from Khe Sanh down there [Lang Vei], but I decided . . . that it wasn't the thing to do." Intelligence indicated that the NVA would attempt to ambush any relief force.

By the end of February and the beginning of March with the securing of the city of Hue, the enemy's countrywide Tet offensive had about spent its initial bolt. Still while the enemy offensive failed, public opinion polls in the United States revealed a continuing disillusionment upon the part of the American public. President Johnson also decided upon a change of course. On 31 March, President Johnson announced his decision not to stand for reelection, to restrict the bombing campaign over North Vietnam, and to authorize only a limited reinforcement of American troops to Vietnam.

Notwithstanding the mood in Washington and ready to begin his counter-offensive, General Westmoreland altered again his command arrangements in I Corps. On 10 March, he disestablished his MACV (Forward) Headquarters. He replaced it with Provisional Corps whose commander, an Army lieutenant general, was directly subordinate to III MAF. At the same time, however, General Westmoreland designated the 7th Air Force commander, as "single manager for air" and gave him "mission direction" over Marine fixed-wing aircraft. Despite Marine Corps protests, Westmoreland's order prevailed. While obtaining major modifications to the ruling, Marine air in Vietnam would operate under the single manager system to the end of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

With the end of the enemy offensive, the allies planned to breakout from Khe Sanh. While North Vietnamese ground forces did not follow up on their Lang Vei attack, they incessantly probed the hill outposts and perimeter. Employing innovative air tactics, Marine and Air Force transport and helicopter pilots kept the base supplied. Finally on 14 April, the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division reinforced by a Marine regiment relieved the base. On 14 April, the 77 day "siege" of Khe Sanh was over.

The North Vietnamese were far from defeated, however, and in early May launched their "mini-Tet offensive". Except for increased fighting in the capital city of Saigon, the North Vietnamese May offensive was largely limited to attacks by fire at allied bases and acts of terrorism in the hamlets and villages. In I Corps, the major attempt was to cut the supply lines in the DMZ sector which led to very bloody fighting, but the defeat again of the North Vietnamese forces.

By mid-1968, the allied forces were on the offensive throughout I Corps. The closing out of the base at Khe Sanh in July 1968 permitted the 3d Marine Division under Major General Raymond G. Davis to launch a series of mobile firebase operations ranging the length and breadth of the northern border area. In one of its most impressive operations, Dewey Canyon, the division crossed the Laotian border in 1969 and destroyed an enemy supply bastion.

From the outset of his Presidency in January 1969, Richard M. Nixon made as one of his chief aims the reduction of U.S. troop levels in South Vietnam. At his behest, the Joint Chiefs of Staff developed a plan for the removal of U.S. forces in six successive stages. The Marine Corps Commandant General Leonard F. Chapman remembered, "I felt, and I think that most Marines felt, that the time had come to get out of Vietnam." The first Marine redeployments started in mid-1969, and by the end of the year the entire 3d Marine Division had departed.