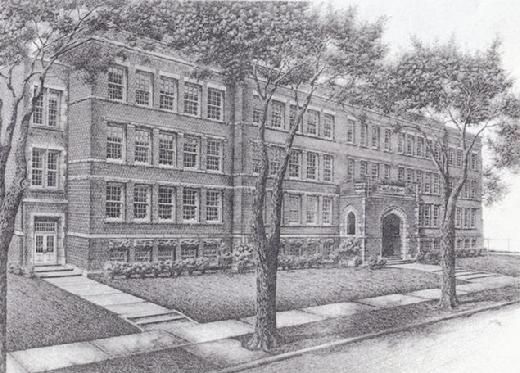

| North High School

Class of 1967

| |

Important Message

This Website Terms and Condition of Use Agreement

also known as a 'terms of service agreement'

Will be at the bottom of most web pages!

Please read it before using this website.

Thank You

|

Loyd Ellis Jones

North High School Class of 1967

|

|

|

| Dec. 16th, 1948 - Sept. 10th, 1968 |

|

| |

|

Click to Listen To The Music!

"Ain't Livin' Long"

By W.C. & The Gold Rush Band

|

Loyd Ellis Jones

Private First Class

M CO, 3RD BN, 5TH MARINES, 1ST MARDIV, III MAF

United States Marine Corps

From Minneapolis, Minnesota

December 16, 1948 to September 10, 1968

(Incident Date September 03, 1968)

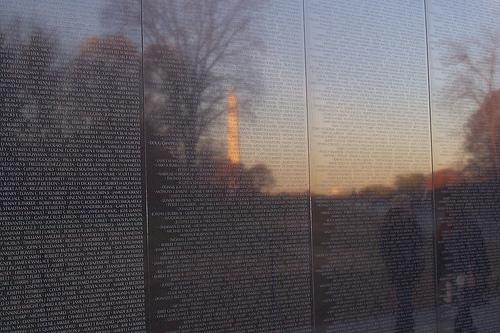

LOYD E JONES is on the Wall at Panel W44, Line 17

Full profile

|

|

| MILITARY DATA: |

| Service Branch: |

United States Marine Corps |

| Grade at loss: |

E2 |

| Rank: |

Private First Class |

| Promotion Note: |

None |

| ID No: |

2430664 |

| MOS or Specialty: |

0351: ANTITANK ASSAULTMAN |

| Length Service: |

00 |

| Unit: |

M CO, 3RD BN, 5TH MARINES, 1ST MARDIV, III MAF |

| CASUALTY DATA: |

| Start Tour: |

06/21/1968 |

| Incident Date: |

09/03/1968 |

| Casualty Date: |

09/10/1968 |

| Age at Loss: |

19 (based on date declared dead) |

| Location: |

Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam |

| Remains: |

Body recovered |

| Casualty Type: |

Hostile, died of wounds |

| Casualty Reason: |

Ground casualty |

| Casualty Detail: |

Gun or small arms fire |

| THE WALL: |

| |

|

| Photo From: Kathy Johnson 8/2016 Loyd Jones name on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. When we were in Washington D.C. |

|

|

|

| Click the photo for more Info. |

|

|

1968

Loyd Served with Mike Company, 3rd Battalion,5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division.

Survived by his mother, Rose V Jones of Minneapolis,MN.

Father was deceased, Laverne Jones.

Burial:

Fort Snelling National Cemetery

Minneapolis

Hennepin County

Minnesota, USA

Plot: Section J Site 2121

| |

|

| Loyd E Jones - Unit in Vietnam |

|

|

September 3rd, 1968

Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam

|

CPL. Ricky Jerome Almanza

Ricky, you always took care of your men first and only then would you take care of yourself. You led by example and with a quiet, calm way that reassured those around you. You were conscientious and did a good job. Although seriously wounded, you continued to help a wounded Marine and pulled him to a safer position. It was an honor to have served with you, and you will not be forgotten..

|

Also Killed In Action on 3 Sept. 1968

|

|

| SSGT GEORGE JOHN BELANCIN Length of service 12 years His tour began on June 15, 1968 Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968 In QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM HOSTILE, GROUND CASUALTY GUN, SMALL ARMS FIRE Panel 45W - Line 30 |

|

|

|

| LCpl. Larry Dale Coats M Co. 3/5 Born on Aug. 1, 1948 From TWIN FALLS, IDAHO Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968 in QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM Non-Hostile, died of illness/injury GROUND CASUALTY MALARIA Panel 45W - - Line 31 |

|

|

|

| PFC. PAUL EDWARD HYLAND Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968 In QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM HOSTILE, GROUND CASUALTY OTHER EXPLOSIVE DEVICE Panel 45W - Line 32 |

|

|

|

| Ricky Almanza, Joe Walters, Jim Quinn, Cpl. Payne, (Marine kneeling, Unidentified) |

|

|

CPL. RICKY JEROME ALMANZA

Silver Star

Born on Oct.16, 1947

From MOLINE, ILLINOIS

Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968

in QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM

HOSTILE, GROUND CASUALTY

GUN, SMALL ARMS FIRE

Panel 45W - - Line 30

|

PFC. TIMOTHY EDWARD SHANOWER

Born on June 11, 1948

From PERRYSBURG, OHIO

Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968

in QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM

Panel 45W - - Line 34

|

Best of the Best

He was the best and the brightest of our generation. Being in his presence, you swore he belonged more in a Chemistry Lab at Ohio State University, then as a Marine with Viet-Nam looming in his future. As a recruit at MCRD, San Diego, he began to shine. First carrying the guideiron of Platoon 135, then as Platoon Honorman.

Later he became Series Honorman, being the best out of 320 Marines. But Tim would have come out on top if it were 320,000. As the rest of us grow older, that kid of 20 that was struck down in '68, will forever be out in front of us carrying the guideiron of Platoon 135 to the echoing cadence of our DI’s.~Lonie Addis

|

Letter from Tim's sister

Here's the pictures to add to Tim's Memorial page. I had a nice talk with Larry Walters and his son (Larry was there when Tim was killed). My brothers and I will be meeting them in the near future. Thanks so much, Debbie Siegel

|

|

| Tim, Debbie and his buddy, "Ray" |

|

| |

|

| om and Pop upon Tim's arrival at home from Boot Camp |

|

|

|

| PFC. TIMOTHY EDWARD SHANOWER |

|

|

|

Click to enlarge photos...

|

Poem Tim's mother had saved with his pictures

I WATCHED HIM GO

I had long known it had to come and I was proud.

But still, I am His Mother

and still He is my Son, my little Son-

mothers are like that.

This morning He said "goodbye";

I watched His tall, strong figure

swinging down the road.

Once He turned and smiled,

His lovely, loving smile,

and waved - then He was gone.

Of course, I shall see Him,

I hope to follow Him

before too long.

But, Ah, how empty this small house is

now He is gone, - how lonely!

not to see Him, care for Him,

hear His kind, warm voice!

No more the quiet talks of evenings

when after supper, we would sit

and He would tell me wonderful things.

Since Joseph died, - dear Joseph! He has been my comfort

God, I understand, I know, and I am glad.

Forgive my mother's longing!

forgive me that I feel

the sword within my heart!

-Mary Willis Shelburne

|

HN Russell L. Wright III

Awarded the Bronze Star

|

|

| HN Russell L. Wright III Born on July 9, 1947 From RICHMOND, VIRGINIA Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968 in QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM Panel 45W - - Line 34 |

|

| |

You Are Missed, My Friend

My name is Gerald Wells, former Marine 1960-1969. I was discharged 26 March 1969 as E-6 Staff Sgt. I first met Russell when he was a civilian in 1966. He was a hip young man dating a 16-year-old girl who was to become my sister-in-law the last day of 1967. I had just return from WestPac as an 0846 artillery forward observer attached to 1-1, 1-3, and 1-9. My unit was A-1-12.

Over the course of the next 15 months or so, I got to know Russell and his mother and father. He often talked about joining the Corps, and I tried to talk him out of it. I was sure he would end up in Nam as a 0311. At some point in time he broke up with Michele, my soon to be sister-in-law, and I did not see him until Christmas Eve night 1967. I turned into a parking lot of a Catholic church driving my 1965 Triumph Spitfire (red), and there was Russell. He recognized my car, and I was so glad he did for it would be the last time I ever saw him.

I was with my girlfriend who I would elope with and marry 6 days later. We were delighted to see Russell. He told me he had taken my advice and not joined the Corps, but had joined the Navy and they were making him a Corpsman. He was in training at Quantico, Va. In civilian life he had trained to be a mortician. He was a darn ditty bopper who played a mean sax, and I always found it hard to believe this guy was learning to be a mortician.

It was a cold evening, and we chatted a few minutes, and he went into Christmas Mass, and we drove off somewhere. Less than 10 days later, I was married and on a Med. cruise attached to 3/8. It seems to me that sometime in March my wife Jackie wrote me with the dreadful news that Russell had been killed in Vietnam. I had lost so many of my own friends there that I had served with, and now Russell.

I know later he was awarded the Bronze Star. His death has always haunted me. He didn't have to go, but like I had done and thousands before and after he went. Any information about Russell would be greatly appreciated by my wife and I. Thanks and good luck.

Semper Fi,

Jerry Wells

|

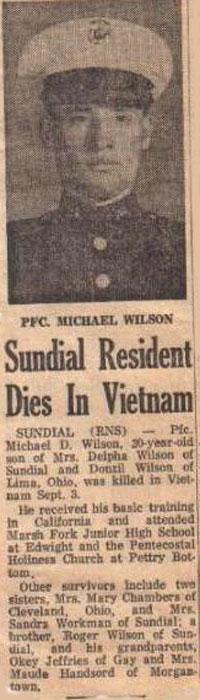

I was in the fifth grade when Michael was killed September 3, 1968 in Mameluke Thrust Operation, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines...Quang Nam, South Vietnam...He was killed in small arms fire...For years and years, I never had a picture of him, and found this clipping from a family friend...only about a year ago. I found one story of the morning of Sept 3, 1968...I sure wish I could find some photo's or any kind of info on Michael...Thanks, Bessie

|

|

| Michael Wilson's Obituary |

|

| |

|

| A Total of 8 Marines KIA |

|

|

PFC. MICHAEL DONVIAN WILSON

Born on Mar. 9, 1948

From LIMA, OHIO

Casualty was on Sept. 3, 1968

in QUANG NAM, SOUTH VIETNAM

HOSTILE, GROUND CASUALTY

GUN, SMALL ARMS FIRE

Panel 45W - - Line 35

| |

|

|

|

| Loyd Ellis Jones |

|

| |

Loyd Ellis Jones

Private First Class

M CO, 3RD BN, 5TH MARINES, 1ST MARDIV, III MAF

United States Marine Corps

|

|

|

| Start Tour: |

06/21/1968 |

| Incident Date: |

09/03/1968 |

| Casualty Date: |

09/10/1968 |

| Age at Loss: |

19 (based on date declared dead) |

| Location: |

Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam |

|

|

| A Soldier's Prayer

(author unknown)

Do not stand at my grave and weep

I am not there; I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow,

I am the diamond glints on snow,

I am the sun on ripened grain,

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning's hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry,

I am not there; I did not die.

| |

Hi floyd,

My name is Bill Lee... I was surfing on the North High School Reunion Site, and saw your 1st Recon stuff. Semper Fi, I was a 1371, Combat Engineer, and was embedded with the

5th Marine Regiment during my combat tour.

Oct 9, 67 - Oct 29, 68.

I was going to attend the reunion, even though I was expelled from North ,(misfit) but just got over committed and couldn't make it. I told Terry Tompkins to keep me in the loop, and I will attend the 50th, God Willing. Thank you for your service.

Bill Lee the photo is me 3/29/68

|

|

| Bill Lee 1968 Click the photo for Bill's Minneapolis North High School Class of '66 webpage! |

|

|

|

| Minneapolis North High - Class of 1967 |

|

|

|

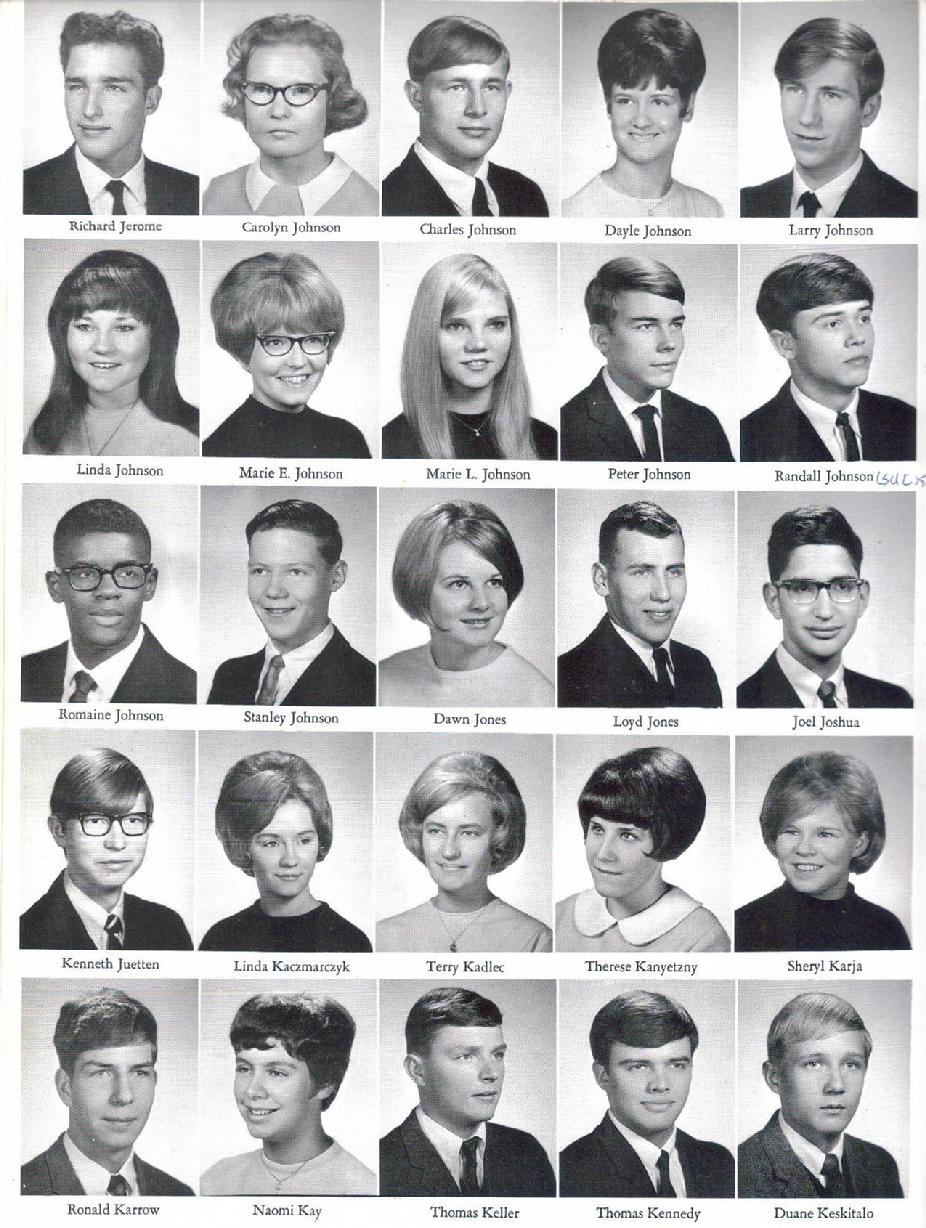

| Minneapolis North High School - Class of 1967 Year Book Page 160 |

|

|

|

| Previous Page |

|

|

|

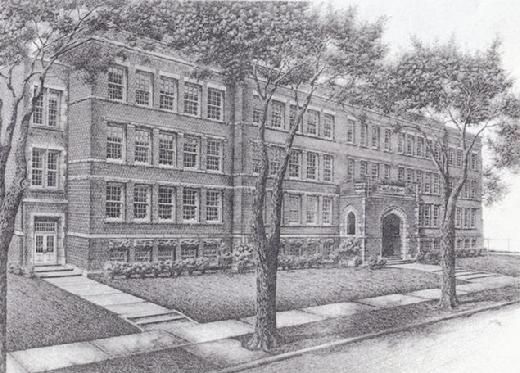

| North High School |

|

|

|

| Next Page |

|

|

|

| Class of 1966 |

|

|

|

| Click the photo for more Info. |

|

|

|

| Loyd E Jones - Unit in Vietnam |

|

|

Mike Company

Third Battalion, Fifth Marines

Stories

RVN, 1968 - 1969

|

(Going to Vietnam - up to arrival at first unit)

by Mike McFerrin

Mid-August, 1968. Realities begin to unfold on the bus to Travis Air Force Base to catch a flight. Final destination: War in Vietnam.

As with all other Marines in that time period, I had known since my first day in the Corps that Vietnam service was inescapable. And I had already seen that more than one tour could also be unavoidable sometimes. I had gone to 5th Recon Battalion at Camp Pendleton in late November of 1967 instead of Vietnam because I was still only 17. By late January, 1968, there were five of us in Bravo Company that were not 18 years old yet. The remainder of Bravo Company were Marines who had already served a tour in Vietnam and were finishing their time in the service there. The Tet Offensive came and there was a major mount-out at Camp Pendleton of several units including Bravo Company, 5th Recon. There was a six hour notice to pack a field transport pack and be ready to board cattle cars to El Toro for a flight directly to Vietnam.

The prevailing attitude about going to Vietnam was to get it over with as soon as possible since most Marines went there immediately after boot camp and initial training anyway. With that in mind, I had even attempted to board the bus to El Toro with Bravo Company. Nobody had said anything about age during the mount-out so I prepared to go and was actually boarding when a sharp-eyed admin sergeant saw me and jerked me off the second step. After numerous written requests to transfer to Vietnam at the earliest, orders came that would give me my 20 day leave, 7 days at Staging Battalion for final training, and have me in Vietnam about 1 week after my 18th birthday.

During the last days of the 20 day leave is when the reality first began to set in. Couldn't really party well because I couldn't get my mind off of where I was going. Then, during an administration process at Staging on exactly my 18th birthday, I was told that I was not going to Vietnam with the others. I would first be sent to the Defense Language Institute in Monterey for a course in South Vietnamese. I tried to decline but was firmly placed with 92 other Marines to be sent to the school.

Now, after 3 months of constant Vietnamese schooling, we had graduated and were being bussed to Travis. Among the 93 Marines was one Viet vet, a Corporal with two fingers missing on one hand from wounds received in his first tour. Rodriguez had always been a source of information on the real Vietnam for all of us at school, but now the questions were becoming nonstop and, to us, he seemed very calm for a man about to endanger his life again. Stomachs were beginning to knot as we took this first leg of our trip to our destinies.

There should have been about a two hour wait at Travis. Our chartered Seaboard World Airlines flight was being repaired and the wait was estimated to be an additional 3 hours. There was another flight being boarded at Travis that caused an overcrowding in the terminal so the waiting Marines went outside and sat alongside of a wall on a walkway in the shade. As it turned out, the walkway was an exit area for arriving flights. We found out when a Medevac flight arrived from Vietnam and the legless and armless living body pieces were wheeled past us to waiting ambulance busses. The Marines, who had been growing quieter as the hour of departure from the U.S. came nearer, became stone silent as the stark visual scene screamed at them about what could happen to them. All 93 Marines had infantry or artillery functions which placed them in line for field positions in Vietnam where these kinds of wounds were sustained.

Late in the afternoon, the flight was postponed until the next morning for further repairs on the plane. The airlines put us up in a motel in Fairfield and bought us dinner. Through the 3 or 4 Marines who were 21, we bought the booze. It was obvious that the liquor was not for partying but for medicinal purposes.

I could hardly wait to get on the plane. I didn't feel good. We were flying the northern route. Seattle, Anchorage, Kyoto, and then to Okinawa for a 48 hour stopover before the final leg to Danang. I needed sleep. It was much better than being awake at this point. There were more delays but finally we were airborne. I slept right through Seattle and awoke as we touched down in Anchorage. We left Anchorage at about 5:30 in the morning and flew east, with over seven hours of spectacular sunrise to Kyoto. It was to be the last beauty I would be able to see and feel for many years.

In Okinawa, current news of the various places of the war was almost always available since it was where all Marines stopped for plane assignment before going to or from Vietnam. This particular year was the war's peak and much was happening. Due to "urgent manpower needs", our 48 hour stopover was reduced to 24 hours. The following morning after arrival at Kadena AFB we sat on the tarmac awaiting our flight to Danang. It was delayed due to a rocket attack on Danang Airbase which had reduced the available runways while repairs were being made. To us new guys, it sounded like Danang had been overrun by enemy troops. Finally, that afternoon we were headed for Vietnam.

As the coast of Vietnam came into view, I could see lots of green and mountains. In fact, it looked like we were approaching a tropical paradise. But as we got closer, this mirage faded. The landscape was heavily scarred. This country looked like it had been bombed to death.

After taxiing to the deplaning point, the airplane door was opened. In an instant, the heat and humidity seeped in and began to suffocate. And the smell. Was that the stench of rotting death? Sweat poured off everybody. We could not deplane until the Marine NCO in charge came aboard. He made us wait until we were near dropping from heat exhaustion.

Here at the Danang airport was where the Marines that had been together for the last three months would end their relationship as classmates. About 12 of us were going to the 5th Marine Regiment. The rest were going to units all over the I Corps region. All of us were to stay in tents along one of the airstrips that night and would be transported to our units in the morning. This scared the crap out of us since we were already catching snippets of real information on the previous night's attack. This airbase was obviously a major target and if they could hit it then they couldn't be far away and we didn't even have rifles yet. We were now in the shit and knew it. If anything comes down here, there's going to be over 90 unarmed Marines trying to grab weapons that aren't theirs, even if the owner hasn't fallen in combat yet.

They began to take 12 marines at a time to the tent area and assigned tent space to them. Then they would come back and get 12 more. I was in the last set of 12 and there was no more room left in the tents. They trucked us a couple miles away to 11th Motors compound to spend the night and leave from there. We were relieved. We felt that we had gotten lucky to avoid staying the night at the airbase. And as it turned out, we were lucky though not as lucky as we thought. The airbase was rocketed that night but only two or three came in, landed far from the tent area and hadn't actually hit anything.

Early in the morning there were both helicopters and truck convoys leaving 11th Motors for various units throughout I Corps. A large number of those who had spent the night at the airbase were brought to 11th Motors for transport that morning. We heard the stories of the rocketing and the near panic that had set in with the first distant impact. All 12 of us and some 30 others were sent to the helipad for transport to An Hoa, the 5th Marine Regimental Headquarters and combat base. A CH-46 was used and it took three trips to get everybody to An Hoa.

I was on the second load out. I did not particularly like helicopters. My first helicopter ride in training had been an old 34. I was sitting on the pull down canvas seat directly across the helicopter from the open doorway. We were flying from the beach at San Onofre in Camp Pendleton up the valley to Camp Horno. A combat ready team does not wear seatbelts. The pilot went into a banking turn and my side of the helicopter rose as the other dropped. Enough that I went out of my seat facing the valley floor hundreds of feet below. As I began to fall across the helicopter, the crew chief who was sitting next to the open door facing me and had a mike to the pilot, yelled to the pilot and stuck his arm out, catching me as the pilot righted the craft. Now I could add being shot out of the sky to my list of fears of ways I might die in a helicopter.

The chopper kept a very tight spiral until a safe altitude had been achieved and then headed south towards An Hoa some thirty odd miles away. As we left Danang we saw much green area with lots of trees and shell holes. Then about 20 miles south of Danang the number of shell holes per square mile increased dramatically. And they looked newer. The door gunner began a constant scan and began to swing the barrel of the gun, prepared to fire in any direction.

An Hoa appeared as a dirt blotch on the southern end of a long valley full of rice paddies with a river bisecting it. There was an airstrip, two artillery units, and some tents and bunkers. The helicopter spiraled down and the door gunner sweated profusely. We took that as a good cue to break into a sweat ourselves. We landed next to the runway which was long enough to accommodate a C-130 cargo plane. We were divided there to go to various battalions. Three of us from language school and 18 others were sent to 3rd Battalion HQ which was a tent just off the airstrip area.

As it happened, 3/5 had not even been to An Hoa yet. They had been up north of Danang since before Tet. The Regiment was in the process of moving to the combat base but only security and the administrative portion had actually arrived. The rest were out on operations. We were split up equally at Battalion HQ, 7 to each of the three companies. All three of us from language school were sent to Mike Company. Chris Sipes, Eric Jorgensen, and I. It felt good to have these familiar faces with me as I entered the Unknown of Combat. This familiarity would turn out to be worthless in bush terms but I didn't know those things yet.

Mike Company office was a tent with a bunker next to it. There was a First Sergeant and a clerk. Our records were given to the clerk. We were sent to Supply for our gear. We put our duffel bags on a pallet in a tent and changed into our jungle fatigues. This was before camouflage in the Marine Corps. They were plain olive drab with leg pockets. The T-shirts were jungle green though and I heard that the boots had metal plates in the bottom. It felt good to have a rifle. I knew if a guy didn't have a rifle, he was newer than me. Then I noticed that all of us who had just arrived could be seen easily clear across the base. Our clothes were greener than everybody else's. And up close the leather part of our boots were blacker than anybody's.

We were to attend a one day indoctrination class here at the combat base and then be sent out to join the company in the field. We were told to stay close to a bunker during the night hours. And they were right. Within minutes after sunset, the mortars began.

This mortar attack became my first inkling of what combat was to be like. As I made a mad dash for the closest bunker, I found myself in a swarm of about 15 other frightened Marines heading for the same bunker that was designed to hold 6 people comfortably. If packed tight, maybe 10 to 12. The mortar rounds were being "walked" across the base. As they came closer to the area we were in, the fear increased and the Marines began elbowing and shoving to get to the bunker doorway that was only big enough for one man at a time to pass through. Though I was scared, I was not panicked to the point of participating in this fighting scramble to get in the bunker. I allowed the panicked Marines to shove past me rather than fight back.

Each Marine that made it into the doorway was immediately pressed into the bunker from the weight of those behind him. There were screams and yells from inside of the total darkness of the bunker as people were stepped on and crushed from the ever increasing weight of bodies. And to further complicate the situation, there was about 4 inches of water and mud in the bunker. The rounds were almost on top of us when a certain scream began to rise above the others. Somebody had his face shoved into this water and could not get out because of the weight. A Marine was starting to drown. This did not slow the rush in the least. I was one of the last to the bunker doorway. The next mortar round was sure to fall on or near the bunker. There was no more room and the scream about the Marine drowning was in front of me as I faced the doorway. There was more panic in the darkness of the bunker than there was from the screeching of the incoming mortar round. I turned and went to the side of the bunker and flattened out on the ground beside it as the mortar impacted about 10 feet away. Two more rounds fell near the bunker and then moved on across the base. The attack ceased within a couple of minutes. Nobody died in that bunker but almost.

I learned a couple of things in that attack. Panic can kill and being flat on the ground can save one's ass even from a very close explosion. And now the war was real for me. I was a target. The next two nights at An Hoa were the same but not quite, since no mortar round landed as close to me as the first night. My world of care and concern had now been reduced to the kill zone of a mortar round.

Late in the afternoon on the third day we stood on the helipad at An Hoa waiting for the helicopter that was to resupply the battalion. It would take all 21 of us to the bush. We would now face all of the other ways the enemy had to kill us. The mortar attacks at An Hoa had given us some preparation for what was to come. All 21 were scared but then we had been scared every night since arriving. The only difference was now we could remain scared 24 hours per day.

About 4 that afternoon the helicopters arrived. We were being choppered to Go Noi Island. It was not really an island but was a large tract of land that lay between two rivers that ran all the way to the ocean some 20 to 30 miles away. It was incredibly hot. Everybody was soaked with sweat. Added to this discomfort was the fact that all 21 of us were carrying gear that we did not need in packs that were arranged and sitting in a way that was not suitable. These lessons would be taught to us when we arrived at our home squads. And the fear of the Unknown. Would the LZ be hot? Would the helicopter be shot down?

Go Noi Island was flat as a pancake with knee high to over head high elephant grass every where except for a few islands of trees and shrubs that dotted the landscape of the interior and followed the river banks. The helicopter began to spiral down to what looked like the exact middle of a sea of grass. There were dots of olive drab running around in the grass, jumping on things that were starting to move from the helicopter's rotorwash. Nobody shot at us.

Upon debarking, it seemed like mass confusion on the ground. We could not tell who was who since nobody was wearing any rank insignia. People seemed to be scattered everywhere without any order. We soon learned that this was the battalion command post (CP) group. We were told that the CP was moving out immediately to join up with the companies somewhere. There were booby traps and gooks everywhere so be careful. This scared the crap out of us. And then to add to that they took the seven of us that were going to Mike Company and told us we would be walking flank for the column. Somehow I was put in charge. They pointed out to where the grass was over head high and told us to go out there and stay 30 to 50 meters out and parallel with the column and, again, to watch out for booby traps. Oh, my God! We were now in the bush. The real bush.

As we moved into the tall grass, we left the air behind. It was like an oven. Sweat was pouring off of us and getting into our eyes. We were taking baby steps as we tried to see through the stinging sweat and grass for a sign of anything that could be indicative of a booby trap. Then there was somebody yelling to me to keep the flank moving with the column which I couldn't see. After about an hour of this we broke through the grass to a small wooded area and there was Mike Company. The seven of us on the flank were dropped off there and the rest continued on to nearby wooded areas that contained the other two companies. At the company CP area, the captain introduced himself, the company gunnery sergeant, and the corpsman. Since third platoon had taken the most casualties in the last few days, three of us were sent there. Second platoon got 2. First platoon got 1 and 1 was assigned to be the new company radioman.

We sat around waiting for the platoon to send somebody up to get us. The corpsman was the only one who talked to us, trying to calm us as the stress of the unknown dangers was obvious in our faces. He told us that the company had been moving across Go Noi on search and destroy and that they had made contact with the enemy every day. We should listen to our squad leaders and try to learn as quickly as possible if we were to stay alive. He was very comforting in his calmness. We felt like he cared.

Soon somebody from third platoon arrived and took three of us to an area on the edge of the wooded ground. Here third platoon was responsible for a section of a perimeter that was being established by digging foxholes about 20 meters apart in an arc that connected with the foxholes of the 2 other platoons forming a rough circle. We met the lieutenant, platoon sergeant, platoon corpsman, and all three squad leaders. One of us to each squad. People seemed genuinely awed that I had been taught to read, write, and speak Vietnamese.

I was immediately assigned to help dig a foxhole. One of my squad was searching an enemy bunker nearby and tossed a wooden plank out the doorway. On it were the Vietnamese words for "Danger: Mine." I wanted to show I knew Vietnamese so I told the guy I was digging the foxhole with what it said. He looked at me and his eyes got real big and he ran over to the bunker yelling at the guy that was entering it. I was stunned since the reality of what I had told him didn't hit me until he ran over there. I got a lot of attention from my new fellow Marines. I knew something that could help them and they seemed to treat me a little better than the other new guys.

Before the sun went down, my squad leader gave me a class on nighttime perimeter defense. How to watch, what to watch, where to watch, how to sleep, how to hold my weapon while awake and asleep, how to prepare my grenades, when to use my grenades, and how to light and smoke a cigarette without being seen. So much to learn. But I was now at the end of the pipeline and it felt good to have a home and new friends. This seemed to help face the dangers ahead. Nothing happened that night and I felt like I was settling in. I would face this war with my fellow Marines.

What I didn't know yet was that although seven new guys had arrived that day in Mike Company, before twenty four hours had passed, there would be eight dead, which included the other five members of my squad, and 14 severely wounded leaving Mike Company. I hadn't yet learned what a "friend" was in Vietnam.

|

FIRST FIREFIGHT

by Mike McFerrin

I had arrived in the bush late in the afternoon the day before. The night had been filled with fear of an attack. At least I had been. The company had only been expecting it. Nothing had happened that night.

I had already been "under fire," so to speak, at the combat base, An Hoa, every night since my arrival there. That is to say we had received a few rounds of incoming 82mm mortar rounds. To me, a new guy, this was under fire. I had now been in the bush some 15 hours without a problem. Only some 12 months and 3 weeks to go. May be I’d get lucky and not see anything.

The reality of the bush was about to become clear to me. One of the squads from one of the other platoons had gone on a short patrol that morning shortly after dawn. They had found and chased some 10 or 12 gooks into a treeline not too far away. The company commander had not allowed them to continue the pursuit. As the squad returned to the company, we were given orders to saddle up. The whole company would enter the treeline to go after the enemy soldiers.

Before 7:30 AM, we moved out in column. The column was maneuvered along the edge of a bushline some 300 meters away and parallel to the target treeline. We made a left face and were now facing the target in a row. The target was an "island" of trees in the middle of a huge area of grass ranging from six inches to knee high. To the right and left of the island were long tree lines about 200 meters away from each side. As we looked at the target it seemed to be about 100 meters wide and perhaps the same deep. It also appeared to contain some hootches somewhere in its interior. We couldn’t actually see any but there seemed to be an order about the trees, bushlines, and paths that we could see that indicated man had been there for a while.

The Captain decided that we would approach the island in a "wedge" formation and enter the treeline at a path that was almost at the midpoint of the island. My platoon got picked for the front of the wedge. My squad was picked for the front of the platoon. And sure as shit, my fireteam was picked for the very point. My fireteam leader decided to take the very point himself and I was a few steps back and to the left of him. We were to wait until we were about 100 meters from the target and begin "reconning" by fire as we approached. It all sounded just like the training formations at Camp Pendleton. Easy stuff.

We moved into the open area and started towards the target. At about 150 meters, our simple maneuver started falling apart. Out of the treeline to the left came one of the other companies in 3/5. We kept moving but it didn’t take a mental giant to see that their column and our wedge would collide at a point about 75 meters out from our target. We were finally halted while the eminent tacticians decided what to do. Their decision caused somewhat of a stir in the ranks because I could hear some mumblings about the stupidity of it. Neither the decision nor the mumblings made much of an impression on me that day as I was on my first field maneuvers in a war and was concentrating on all the things I was supposed to do such as distance and direction between myself and the other men, watching for enemy movement in the trees, etc.

The decision had been to have Mike Company stop its wedge formation assault on the treeline and allow the other company to cross in column between it and the target. I now see how ridiculous that decision was and why everybody groaned and mumbled. We were approaching this treeline as if there were a large number of enemy troops in there ready to fight us. But for a few moments we would pretend there was nobody in there and another Marine company would walk right across in front of this treeline as if they were just walking by minding their own business. This probably looked good on paper and surely the gooks, if they were in there, would honor this little time-out we called. I mean it would certainly be unsportsmanlike for them to wait for the column to get spread out directly in front of them with the wedge formation directly on the other side of that column then open up with Marines two deep in front of them.

Of course, that was exactly what happened. Due to the heat the Marines of Mike Company had sat down to wait for the other company to move across. I was a new guy so I had a helmet. Not all of the non-new guys wore helmets. Some wore bush hats of various types. I sat on my helmet wiping the sweat from my brow. All of a sudden, the air burst into whizzes and whines of bullets. The cracks of dozens of AK’s firing at once followed the bullets across the grassland. And behind that the screams of the wounded and dying.

I rolled off my helmet instantly and flattened on the ground. There was no cover anywhere. And none of us in Mike Company could return fire anyway since the other company was in front of us. Bullets were striking everywhere around me. I tried to crawl underneath my helmet. My terror was increasing as the realization that there was nowhere to go came over me.

Then I heard a yell from behind me to my left. They didn’t know my name yet so they called me "New Guy." Three Marines had found a small rise that offered some cover and on the other side of them one Marine had found a small shell hole that had room for another person. I raised my head just enough to see them as they told me to come over there. It was probably no more than ten to fifteen meters but the bullets were thick enough to walk on so it looked like a click or more to me. I said no to the requests that I come to their cover. No way.

Then as I turned my head back to the front and began lowering it back into the earth I saw an automatic burst of fire parting grass and striking dirt about fifteen meters in front of me and tracking directly to me. I paused only a second and rolled my left shoulder, leg and head to the right. Right where my head had been and right in front of where my face now was a bullet struck. Dirt was kicked into my right eye from the impact. One more round hit about where my kidney would have been. The burst ended with that round. I yelled over and asked if they still had room for me. They did but again I found it difficult to move. This seemed more impossible than dodging raindrops in the monsoon. I was trying to figure my odds of getting hit staying there versus moving to cover. There’s one for Einstein to figure.

As they coaxed me to come and I vacillated, a blood curdling scream and cries for help came from behind me to my right. I could not see who got hit but the sound was very close. In an instant I low crawled, no, I slithered, dragging my face in the dirt to the cover of the shell hole. The cries for help over to my right began to slow down. Then there was nothing.

To the front, the fast and furious cracking of AK fire began to slow. The screaming and yelling of the Marines seemed to get louder. I looked up and could only see two Marines out there and they were running back toward the treeline from where they had come. Then I could see some more Marines back in the treeline who had apparently made it to safety. But there were still people yelling for help down there. I quickly raised up a little higher for a quick glance. I could see five or six bodies laying in the grass in front of the island. The AK fire slowed to a burst every ten or twelve seconds. After about a minute of this, it seemed to stop completely. I was thinking the gooks must be dead or ran off.

The screams for help were really loud now. My fireteam leader jumped up, turned and looked at us and said to drop our gear and follow him. My first order to follow in combat. I dropped my pack and jumped up to follow my fireteam leader. The other Marine in the shell hole with me yelled at me to not go and said something about me being sorry for doing that. It wasn’t registering because I was so scared and new that I was focused on what I had to do.

The fireteam leader said to follow him and I did. He began running out to the wounded Marines in front of the island. We had gotten about halfway there when my fireteam leader yells at me to zig zag. I said, "What? They’re all dead aren’t they?" He yelled, "NO!!!" I glanced behind me and saw that not a single other Marine had come with us. UH OH!!!! I almost shit my pants. This guy is a nut or a hero and I am the only one stupid enough to follow him out here. By now, we are almost three quarters of the way there and I want to stop my forward motion and run back. As I slow though, I get scared that I am starting to offer myself as an easier target and simultaneously I see four other Marines from the other company come running out of their treeline towards the wounded. Then there was a short burst of AK fire. Both my fireteam leader and I dove to the ground right where all the wounded Marines were.

My fireteam leader crawled up to a Marine who had been shot in the butt and/or thigh and yelled at me to come and help. The Marine was ashen faced and trembling severely. It was hard to tell if it was from the wound or the experience of being abandoned to die for the last five minutes or both. My fireteam leader pulled the guy’s poncho off his pack and told me to spread it out next to him while he took the guy’s battle dressing from his helmet and applied to the wounded area. We then rolled the guy onto the poncho and began to drag him towards the treeline. By this time other Marines from his company began to come out to help and two of them took over the front part of the poncho while my fireteam leader and I picked up the back end and we carried him all the way to safety. The wounded Marine was thanking us and promising us a bottle of booze each for saving him.

My fireteam leader and I went partially back out once more to help finish carrying one more. Then we went along the treeline until we were parallel to where our company was and dashed across the open to them. This time I dove behind the little rise with the three Marines behind it. I was amazed that we had pulled it off. I was sure that my fireteam leader at least would get a medal for this. I don’t think anybody would’ve gone out there if he hadn’t gone first.

We heard the order being yelled to pull back. All the way back past the bush line where we had started and into the trees. My fireteam leader and I were the first to respond since we had already been running all over the place. I only went a few steps back when I saw the dead Marine. It was my platoon sergeant. I yelled to my fireteam leader who recruited a couple of others to help pull his body back with us.

As we dropped his body at the makeshift LZ, my fireteam leader looked to me and told me I had first shot at anything I wanted from the platoon sergeant. I didn’t know what he meant. Then some of the other Marines began swarming around. One noticed that there was a K-Bar (knife) and told me that if I didn’t want it, he did. Now I understood. We were going to go through the dead platoon sergeant’s gear and take what we wanted. This seemed somehow unholy. I hesitated. I was told that K-Bars were non-issue gear and were prized possessions because of their usefulness in the bush. I might not ever get one if I didn’t take this one. I passed on participating in what seemed at that time to be a ghoulish practice. And yes, before 3 days had gone by, I couldn’t believe that I had been that much of a boot.

The Captain came over by my platoon and in a very gruff voice asked who that was that had run out to help the wounded from the other company. The other members of the platoon pointed us out before we could say anything. The Captain approached us and started yelling at us. Nobody had ordered us to go out there and who the hell did we think we were running off from our company to help another company, etc. I was dumbfounded. I guess I wasn’t just a dumb new guy following a hero but a dumb new guy following a fuck-up. Later I learned that the Captain had basically frozen during the incident as much from the shock of realizing that the entire situation had been caused by the stupidity of the maneuver he had ordered as from fear. I think he was compensating by striking out at us trying to make us look like idiots to everybody.

Medevacs were called in. Later I learned that there was an attempt to call in air support but that the delay in getting it was unacceptable since it would stall the operational plans. We would pick up where we left off. We would assault the treeline with our wedge formation. No guessing this time. They were in there. Oh, shit!

After the Medevacs left we reassembled into the wedge and were told to walk fast towards the treeline and to begin recon by fire immediately. I tried to put a wall of lead in front of me more in hopes of stopping any bullets headed at me than killing any enemy soldiers. There was no return fire yet. At about the halfway point, I had to change magazines. I think two bullets fired out of the new magazine and it jammed. Whoops! Here I am walking at almost full speed towards the enemy and I don’t have a weapon. I slowed then came to a full stop as I tried to unjam my weapon. This messed up the wedge so my squad leader ran up and gave me his M-16 while he cleared mine. I caught up to my place and began firing and this one jammed too. Shit! Still no return fire yet though. My squad leader ran up again with my now cleared M-16 and grabbed his to clear it.

We were now down to the last 100 meters and I think everybody started slowing down a bit expecting the worst. About 25 meters out from the edge of the island was a bamboo thicket with about a 3 meter radius and well over head high. This was in front of me so I began to sort of use it for cover as we approached. This was the only cover available if the shit hit the fan. As I neared it, I realized that I would have to step to one side or the other to get around it and I would no longer have it available for cover after I passed it. I walked right up to within two arms length of it not having made my mind up yet which way to go around it. I sort of hesitated and looked around to my left to make sure the rest of the wedge was with me.

As I swung my eyes, I saw something and quickly looked back at the bamboo thicket in front of me. Resting in between two of the large pieces of bamboo at about four inches above ground level was the end of a barrel. I squinted my eyes to peer through the slit and followed the barrel to the other end. Our eyes met and locked. My rifle was pointed off to the right of the bamboo thicket. His was pointed directly at my chest. I know I gasped. I’m sure I paled. But the locking of our eyes apparently scared him, too, because I saw his eyes get real big and he ducked his head way down into the hole he had dug in the middle of the bamboo thicket. At the same time he opened up with what I now believe was an RPD machine gun. When he ducked, the barrel dropped and two or three bullets went between my legs before he started swinging it to the left to get the other Marines that he could see.

All hell broke loose. All the gooks back in the trees and vegetation of the island opened up. They tore up the advancing wedge. As the machine gun barrel swung away from me I fell flat to the earth directly in front of the machine gun. I was trying to swing my M-16 back forward when the barrel swung back towards me. I cringed expecting the top of my head to be split open. It passed right on over me and killed several people on my right. He must think I’m dead. He did duck when he fired. As I listened to what was happening around me, I knew we were getting our ass kicked.

I rolled my eyes up to try and see in front of me. The grass was some eight to ten inches high and I could not see the slit in the bamboo where the gun was. And my rifle was still not pointed in that direction. I now know he probably couldn’t see me either because of the grass but it did not occur to me at that moment. My predicament began to sink in and terror began to grip me. Just then the corpsman ran up and knelt down next to a guy off to my right. I tried to yell but could only squeak, "Doc, he’s dead!," just as the machine gun opened up and put a couple of bursts into his chest. As he fell over the dead Marine he had come to help, I began to cry and my head spun as I prepared to die.

My first thought was of a Marine officer telling my parents that I had been killed. My second was that I had been killed in my first 24 hours in the bush which certainly didn’t speak well of me paying attention in my Marine training and might even be embarrassing to my parents. It certainly was to me. Then my life began playing itself to me as vividly as any 3-D movie I’ve ever seen. I was crying but not making any sound. Nor was I moving. I would rather live frozen stiff like this than die. Ants began to crawl on my head and face. Whenever they got close to my mouth I would try to bite them. I could see my home as I seemed to be floating at about mid-tree level around it. I saw my family and friends. And it just kept going.

The Marines began to pull back. They would call out the names of everybody who wasn’t moving back with them to see if there were any wounded who needed help. They were calling six names out that didn’t answer even after repeated efforts. The five dead on either side of me and mine. I wasn’t about to answer this roll call. Then they left. And I was alone with the dead Marines and live gooks.

They pulled all the way back past where they had been before. Almost 400 meters and totally out of sight. As far as I knew they had gone to An Hoa. Or Danang. Or even back to the World. It didn’t matter. Even if they knew I was alive, I was right in front of the machine gun that they still might not know is there. Even if they did, what could they do? I would be killed in the crossfire. I cried for my death at such a young age. What a harsh world. I began to pray. And I mean for real. I began to see the things I was allowed to see. Life was a natural event. Death was also. I began to feel as if I had been here before, dying on a battlefield. All of a sudden with a shock that convulsed my body, I understood. My tears stopped. My sorrow and self-pity evaporated in an instant. Whether it was here or in a hospital at 100 years old, I would experience Death. And it was not bad. I fully accepted my own mortality. The only measurement that would apply was how I had lived. I had been in front of that machine gun for over 45 minutes crying. I thanked God for letting me live long enough to arrive at this point.

I still believed that there was no feasible way for me to get out of this situation. I only knew that I would not lay there and die crying for myself. I decided that I could help my fellow Marines out if I could take this machine gun out. Then they at least stood a chance of recovering our bodies without another death. I remembered that I had been issued a little grenade pouch that holds three grenades and it was on my web belt on my right side. If I could get a grenade out and the pin pulled before he killed me then maybe the grenade blast would be enough to penetrate the bamboo and kill him too. I very slowly began moving my right arm back alongside my body. It must’ve taken two or three minutes. Finally I could feel the pouch and I unsnapped one of the pockets and the grenade rolled out next to me. I felt for it, grabbed it, and spent another two minutes moving it up to the top of my head. Now I needed my other hand to pull the pin. Finally the deed was done. The grenade was ready and I wasn’t dead yet. I decided it stood a better chance of getting him if it was right next to the bamboo.

With my arms extended over my head, my hand was only an arm’s length from the bamboo. I simply opened my hand and gave the grenade a little nudge. I fully expected it to kill both of us. I didn’t even cringe. I was ready to die. The blast was incredible. It took my helmet off and felt like it split the skin on my forehead open. I couldn’t hear but hadn’t seemed to die right off in the initial blast. I couldn’t feel any pain except the skin of my forehead. I wondered if the gook was dead yet. I was so stunned from the concussion I couldn’t be sure how bad I was wounded.

Mike Company was calling in choppers for the wounded and dead that they had gotten out and were also attempting to get two "stacks" of air (4 Phantom jets) to do the island in. I was so new that I did not know that this was pretty standard in these type of situations. I had no idea that they were going to drop napalm and high explosives on the place then strafe anything that was left. I am really glad that I did not know. Fortunately for me, there was a great deal of action somewhere else in I Corps that day and they were unable to get the standard rapid response.

But people in Mike Company heard my grenade go off and knew that somebody was still alive up there. A squad came back and attempted to move up. The machine gunner in the bamboo thicket opened up on them. I almost shit my pants since he was firing directly over my head. Shit! Not only did I not kill myself with the grenade, I didn’t even incapacitate the machine gunner. The thought crossed my mind that I was not very good at this. But I also decided that maybe I should try to get this asshole without killing myself. Again I reached back for a grenade from my pouch. I moved a little bit more confidently this time. I realized the grass must be hiding most of my movements. But when I began to move, a sniper up in a tree back on the island saw me and began firing. The bullets were single shot and began hitting three to six meters from me. This did not slow me down whatsoever by this point. I was right in front of a gun that could split my skull open. The sniper fired five rounds at me and I realized that the "plunging" fire angle that he had must be difficult and/or this son-of-a-bitch needed glasses. This time when I got the pin pulled I stretched my right arm out as far as I could and threw the grenade around the side of the bamboo thicket so that it provided some cover for me.

Right after the explosion, the Mike Company people again tried to move up and again he opened up on them. But now they knew that I was somewhere in front of the thicket and that I was targeting the thicket as the source of enemy fire. I heard a yell in the distance from the Marines who were trying to get back up to the area, "Hey! Keep your head down!" I wondered what idiot thought he had to holler that to me from a couple of hundred meters away. All of a sudden there was a whoosh and a short sound of sucking air and then a horrific explosion as a LAAW rocket fired from that distance made a direct hit on the thicket. The blast and the shrapnel all moved forward into the thicket but the pure concussion that reached back for me was incredibly strong. My entire body, in the prone position was lifted above the top of the grass and dropped back to the earth banging my chin very smartly. It was a hell of shot somebody had made. Since the Marines had actually witnessed my body come up above the grass they now knew that I was not just somewhere in front of the thicket, but was literally right in front of it. I heard the same voice yell, "Hey! Don’t worry! We won’t fire another one."

To show them that he was still there, the enemy gunner immediately fired a short burst towards the Marines. Christ!!! I had no idea how he was not being affected. Boot as I was, I was not aware of all the weird holes and side holes they dug inside of large rooted plants and trees that gave them such good protection. But the other Marines knew. Somewhere with one of the other companies on Go Noi were a tank and an amtrac. This was the one and only time that I ever saw either with the bush companies in the bush. The tank was sent up to get me.

I did not know there were tanks out with us. Until I began to hear and feel the rumble. The tank approached the island straight ahead about one hundred meters to my right. I heard the yelling of the Marines to tell me that they were sending a tank to get me out. I suddenly returned to the normal world. I was no longer alone waiting to die. I was elated momentarily. Then slowly the elation began to die down as I tried to figure out how this tank was going to "get me out." I couldn’t see any reasonable way. The elation dissipated but not the new found hope.

When the tank got to the same distance from the island that I was, it made a 90 degree left and came straight at me as if to drive between me and the bamboo thicket. Once it had made this turn, one of the crewman reached up and grabbed the 50 caliber machine gun mounted on top of the tank and began firing it as he swung it in a wide arc spraying the island from the top of the trees to the bushes on the ground. And the tank continued to come at me. I realized that the driver probably couldn’t even see me laying in the grass and the guy up on the 50 wasn’t looking at anything but the island. I was watching 52 tons of steel come at me and it wasn’t slowing down or turning.

From some two to three hundred meters back, I could hear Marines yelling, "Run! Run!" It was becoming clear that my options were limited. I watched as the tank rolled up on me. I was waiting for the last second to get as much tank cover as possible from the snipers back in the trees and hopefully the closer it got the more likely the gook in the thicket would have his head down. Just then the Marine up on the tank firing the 50 cal turned and looked at me and yelled at me to run behind the tank. In the blink of an eye, I did just that. The tank stopped right in front of the bamboo thicket as I got behind it.

From behind the tank, I yelled up to the Marine telling him that the gook was in the bamboo. He yelled back at me to run straight back to the company keeping the tank between me and the island. He turned the 50 cal almost straight down and fired into the thicket. I began to run. As I moved away from the tank I knew that I was presenting a target to the snipers in the trees and so did my feet because they moved like they never had before. The last grenade in my pouch flew out somewhere in the grass as well as several other unidentified items in my pockets. It didn’t matter what it was, I was not slowing or stopping for anything.

As I made my mad dash, I could see the heads of a couple of Marines as they yelled for me to come to where they were at. When I got close enough, I dove for them. As I slithered around in the dirt to bring my head up with the other Marines, I realized I was in the same shell hole that I had sought cover in early in the morning. But now it seemed like it was years ago. One of the Marines looked at me and asked if I was okay. I said that I was but asked, "Is it like this in Vietnam every day?" He responded with, "Nah. It only gets this bad two or three times a week." I lay there thinking of what had happened to me in front of that machine gun. I had been irrevocably changed. I had accepted my own mortality and was no longer afraid of it. And it was a good thing because it did not look like surviving 13 months of this at two to three times a week was a good bet.

The tank withdrew some 20 meters, swiveled its cannon around and blew the entire thicket away. Then it retreated to the CP area some 100 meters behind us in some trees. Shortly thereafter, the air support arrived. Four Phantom jets. First they dropped napalm on the island. This was my first view of an air strike. I was astounded. The flames rolled through and totally engulfed the island. Nothing could live through that and yet they did it again. And again. Four times they hit the island with napalm. Then four times they hit it with HE (high explosive) bombs that shook the earth and toppled the trees. Then, to my amazement, they began making passes to strafe the island. I asked one of the Marines what they were shooting at since I didn’t think anything could have even survived the napalm, much less the HE. He said, "Ol’ Mista Charles ain’t dead. He’s just sitting in one of his tunnels waiting for the jets to leave."

While the strafing runs were still going on, the Captain yelled to my Platoon Commander to get the platoon ready to go get the bodies. He yelled to another platoon to set up a base of fire to cover us. As the last strafing run was made, we were told to move out running zig zag and get the dead Marines. I was still of the mind that there were probably no live gooks though. The other platoon laid down a very heavy volume of fire as we moved up. They kept shifting the fire as we moved into its range. We did not receive any fire from the island.

I helped get the body of the corpsman who had been killed next to me. Four of us struggled to run with this body some 300 meters. It was an ass kicker. He had a large pack on and one of the squad leaders said to carry him back with it on because it contained medical supplies that we might need. We put the dead next to a clear area that was to be used for an LZ. I could not take my eyes off the corpsman. This was my first in several ways. The first that I watched as he was killed. The first person that I knew, even if only for a few hours, that I had seen killed. The first dead body that I had clearly seen. I studied his face. The bullet holes in his chest. I thought of him as a person. His family. I had a sick feeling in my stomach.

The choppers finally came and took the dead and wounded. It was 1530 hours. We had been at it for about 8 hours now. I had been extremely exposed to death twice so far. I had undergone a psychic and emotional upheaval of the greatest magnitude in front of the machine gun. I hadn’t eaten or drank anything since about 6 that morning. And it was over 100 degrees. I was totally wasted. My stomach was in such knots that I couldn’t put any food in it. But I began to drink water ferociously. The Platoon Commander came over to me and warned me to stop drinking like that. He also seemed aware of what I had been through because he asked me if I thought I was going to make it through the rest of the day. I assured him that I was capable of continuing. But when I said that, neither one of us knew what the end of the day was going to be. If I had known, I might have changed my response.

After about a half an hour of cooling off, the Captain passed the word that we were going to "take the island." This did not seem to be much since it had been napalmed, exploded, and strafed and we had been able to get the dead without being fired upon. They were dead or had made their didi out the back. This time even the veterans believed that. To be safe, we got on line as a company and moved towards the island firing as we went. There was absolutely no return fire as we moved all the way up to where the point of the wedge had been earlier at about 25 to 50 meters out from the tree and bush line that marked the edge of the island. As we moved into this last space, the elephant grass began to get taller. By the time we were 10 meters out it was over head high and so thick that you could only see just past your nose and so stifling that you had to struggle for a breath.

And the shit hit the fan. Again. The AK’s seemed like they were right next to us. We were blind in the grass. There were no targets visible. But we were not visible either. Everybody hit the deck where they were and began pumping out the fire. There was 3 or 4 minutes of sustained fire from both sides as each sought to put out a wall of lead to kill their invisible enemy. Then the fire slowed to an occasional pop or two from each side as each tried to assess the effect that their initial, long volley had. The Captain and Platoon Commanders were behind us and couldn’t actually see us anymore. They yelled a couple of times about charging through the grass. No one responded to that. It did not take a Field Marshal to figure out that the gooks were sitting back away from where the grass ended at the edge of the island. As soon as a Marine poked his head out, every gook would be firing at him before he could even take in the view to see what was there. And even if he ducked back in the grass, there was no cover and they would concentrate their fire on the spot until he was riddled. There were some wounded Marines but they were able to back out of the tall grass and get to cover.

For the rest of us, the order to charge was modified by us to mean to keep crawling forward until we could see the edge of the island. Then maybe we could spot targets and assess what to do. But this was not easy or simple because the volume of fire became sporadically heavy as we tried to suppress their fire so that each of us could crawl up a meter or two then be sure the rest of the line had moved up as close as possible to parallel with us. This basically had to be done by voice since most of us could not see each other either. To get off line now could be disastrous. Without sight, we had to be able to assume that a 180 degree arc in front of us was the enemy and the other 180 degrees behind us was friendlies.

Then the first call from one of the Marines that was a signal of incredible significance. He called for somebody to throw him some ammo. It was then that I, and everybody else I’m sure, looked at their own ammo supply. Shit! Out of the two bandoleers of ten magazines each, I had four left. At the rate that I was firing, they’d be gone in a couple of minutes. The squad leaders began calling to their squad members to get a count. The story was pretty much the same for all of third platoon at least. This meant that we would not be able to continue advancing the way we had. They ordered the squads to stop firing and hold their place where they were. If the enemy decided to assault us in the grass, we needed a straight line and ammo to be able to repulse them.

We couldn’t be more than 5 or 6 meters from the edge of the island. We tried to move up one by one another meter but every time the enemy heard the rustle of grass they poured out huge volumes of fire. And we were unable to respond and put their heads down. We tried several times to have many M-16’s firing single shots but it couldn’t even be heard over the din of the AK’s and RPD’s. This went on until darkness began to arrive. It was decided to hold the ground gained for the night. To do this, the squad leaders had us inch sideways into groups of two or three that were close enough to touch each other even if we couldn’t see each other. These groups were our positions for the night. As the sun set, it became incredibly dark in the sea of grass that we lay in the bottom of. All firing from either side stopped and dead quiet set in.

The word was passed that more ammo would be choppered out in the morning and to redistribute remaining ammo between Marines in each position to insure all had some. I had a little over one magazine left and a magazine and a half after redistribution. As it cooled down my hunger grew. I began opening cans in the dark not being able to see what I was getting and not caring. I ate 4 cans of whatever before I started guzzling water. My body was thankful.

As the food and water worked its way through me, I lay face down in the dirt and pondered the new world I had entered. Sometime late in the afternoon, I had passed the twenty four hour mark in the bush and was now in the second day. My first firefight had lasted since before 8 that morning to almost 9 that night and was, in fact, still not over but just in a timeout due to darkness. I was just a teenager yesterday. Now I felt like an old man. People had been killed and wounded all around me for hours now. I had escaped a sure death situation. But the words of the Marine earlier in the day about this happening like this 2 or 3 times a week rang in my head. How could I, or anybody for that matter, survive thirteen months of this? It didn’t seem like a very good bet. I became pretty well convinced that night that I would not finish my tour before becoming WIA or KIA. I wondered how the war could have been going on for three years now at this level and I had not heard how bad it really was.

I did not sleep much even though I was totally exhausted. There were 3 Marines in my position so we had it relatively good. A potential of 4 hours of sleep. But the fear of the enemy crawling through the grass and the visions of the dead Marines that kept floating through my head made that impossible for me at least. In reality, the night was uneventful but in my head everything that twitched from the ants to the sleeping Marines was a full frontal assault on my position that was about to take place. I was still determined to die fighting.

In the morning, the company CP group moved back to the area where the choppers could safely land and got a load of ammo that was sent in. They moved off to the right side of the island and approached the edge of the very tall elephant grass on their bellies from there. They began throwing boxes of M-16 rounds into the grass and adjusting their throws based on voice commands from those of us in the grass. There had not been a single shot fired yet by anybody but all the blood stained ground and grass was there to remind one of what would happen when it did begin. Once everybody had reloaded, we waited for the word to move forward.

It didn’t come right away and we could hear the officers talking behind us somewhere. It seems that the Captain had used his binoculars when they were back getting the ammo and had spotted what appeared to be a bunker just inside of the trees of the island. After conferring with the Platoon Commanders, the decision was made to focus on this one bunker rather than a company wide assault. If the one bunker could be taken then the company would be able to get into the trees on the island and inside the enemy perimeter. I guess that sounds pretty good tactically speaking. But then the orders to implement this were passed down and I almost shit my pants. The bunker was situated in dense vegetation that would only allow for a few men to assault it at once. The seven men closest to the area would be designated a "new" squad since the squads were pretty well decimated anyway and they would assault this bunker. Sure as shit, I was one of them. I couldn’t believe it. I was the only one of the seven who had been in front all of yesterday. What the hell?

We were told to inch our way sideways for about 10 meters. Then we were to inch our way forwards to the edge of the grass. No one was to open up unless the enemy did. I guess the idea was to not announce our intentions. This whole process started out very, very slow but speeded up a bit with the lack of fire. In about 20 minutes, I was able to see through the last blades of grass and spot the bunker. As it turned out, the available lane of approach was even narrower than thought so two of the seven were to stay back and fill in when somebody fell. Of course, I was not one of the two. It seemed like the Marine Corps was arranging this entire thing just to get me killed. Every time I escaped with my life, they came up with another reason to put me out front.

I heard some voices behind me and the Platoon Commander called to the squad leader to hold. They were bringing up the tank that had saved my life yesterday. I was told to keep moving to my right. I had one person on my right who had to move with me. The other 3 moved to the left. The tank pulled up between us. The Platoon Commander yelled to us that the tank was going to fire its cannon at the bunker and that he would give us the order to charge. This felt like a reprieve for sure. The tank lowered its cannon and fired. It was a deafening roar and explosion but it only scratched a little dirt on the bunker. The tank was ordered to fire 2 more times. It shook the shit out of the bunker but again there was no visible damage.

The tank backed up and we got on line and were told to charge. Oh God! Here I go again. Immediately the Marine on my right fell to the ground. I looked at him and his eyes were as big as plates. He said that his rifle was jammed and he’d catch up later. I knew that he had just chickened out and nobody was moving up to take his place. All I could think was the son-of-a-bitch was deserting me under fire since he was part of my cover fire as I was for him and the other guy next to me. There were now 4 of us assaulting the bunker. We only had about 25 meters to go. We yelled and screamed and laid down automatic bursts as we ran forward. Since I was a boot though, I wasn’t familiar with the enemy bunkers yet and had no idea that there were multiple entrances. I kept my fire focused on the only doorway that I could see and the gun slot in the front. I fired back and forth. We kept bullets pouring in and no one fired back. As we got right up to it one of the Marines leaped forward and threw a grenade in the slot and yelled at us to get down as he dove to the far side of the bunker.

He let out a scream simultaneous with the explosion. This scared the shit out of the other three of us since we thought that we were being assaulted from the other side of the bunker. We leaped on top of the bunker facing to the rear of it forming a hasty arc of defense to repel the assault. Off to the side we saw the Marine who had thrown the grenade rolling around on the ground. There were no gooks assaulting us. The Marine who had thrown the grenade had leaped in front of one of the exits to the bunker for cover and had caught a piece of shrapnel from his own grenade in the shoulder. As the situation became clear, we threw a couple of more grenades into the bunker and called to the rest of the company. They then flooded into the area moving some 50 meters or so beyond the bunker to set up a defensive line as we entered the bunker to clear it. Things were beginning to go in my favor as I did not have to enter the bunker first. There were 4 dead gooks and one severely wounded in there.

We spent some four more hours on the island securing and searching it. We took no more fire and found no more live gooks. Some 29 hours after my first firefight had begun it was over. The quiet and lack of "electricity" in the air was disconcerting. Everyone kept looking and waiting for something to happen but it didn’t. We then were ordered into a column to move out the back side of the island. No destination was given. Just follow the man in front of you. As we left the island, I was overwhelmed with awe at what was happening. After over 24 hours of combat and all of the spilled blood to take the island, we were all just walking away from it. I groped for comprehension of what this was about. I turned to fellow Marines and asked why we were just walking away from this. Why weren’t we leaving Marines behind to hold it?

"That’s the way it is in Nam. We don’t hold nothing here, man. We just roam around out here waiting to find Charles or waiting for him to find us. We kill some of him and he kills some of us then we go do it somewhere else."

I was totally stunned as I thought of all the horror that had transpired and the near sacrifice of my life. It boiled down to this. The only prize to be won was my own life. And it was the same for all of us Marines. At least the other side had the illusion (or maybe not so much of an illusion) of us as an invading army to motivate them. We didn’t even have that. If there had been any traces of the illusion of fighting for Freedom, Truth, Justice, the American Way, or any of that other John Wayne movie bullshit in me, it was completely erased as the island faded into the background behind the column.

The near death experience in front of the machine gun had transformed me emotionally and psychically. The realization of what was happening here did the same for my wisdom and political maturity. I was not who I had been nor could I ever be again.

Over the course of the next couple of years, I would come even closer to death many times. I would be in battles that surpassed this in length and ferocity. But none would ever match this first one for the totality of effect that it had on my life in total. All that I have ever done since then has had the stamp of that experience on it.

|

OVERRUN!

By Mike McFerrin

Somewhere near Henderson Hill. Late 1968. Maybe October or November. Operation name not remembered but the Operation itself well remembered. Classic hammer and anvil, sweep and block, the rock and a hard place. Memorable because of two things. First the battleship New Jersey used its large guns as part of the sweep. Biggest craters I've ever seen. Second, the operation actually worked. Large numbers of NVA soldiers running right to us trying to get away from both the New Jersey's guns and a battalion of 5th Marines sweeping from Go Noi.

This was my first operation as a squad leader and I had been blessed with a squad of "new guys." Boots from head to toe. I believe I had six men in the squad which was not unusual at that time. Don't believe I ever saw a full strength squad in Mike Company. Six boots, myself, and my radioman who had come to the bush at the same time as I had. This was a test I was not eager to take.

I had, by necessity, become proficient at many disciplines in the bush but had never, ever done so for any other reason than to keep myself alive. Map and compass, fire support direction and control, ambushes, trail signs, tactics, first aid, camouflage, mine and booby trap detection, explosives ordinance disposal, enemy weapons and tactics, etc. were all a part of my still developing repertoire of skills that were being honed simply to allow me another hour or day or week of Life. Twenty four hours per day I was consumed by the perceived need to know all of these things to the Nth degree. I had actually become a bit of an annoyance to the platoon sergeant and platoon commander as I developed questions every few hours that I would hit them with at every possible opportunity including when they attempted to go relieve themselves. Now they were making me pay for it by making me a squad leader. I had enough trouble keeping myself alive. How was I going to keep anybody else alive?

We left the forward CP outside of An Hoa on the road to Liberty Bridge in the morning. Prior to moving out, I gave my "boot collection" a quick class on step 1, moving down the road in daylight. We followed the road north about halfway to Liberty Bridge than moved west off the road to some high ground and waited as the New Jersey and the guns from An Hoa began pounding the area on both sides of the river to the north that marked the southern edge of Go Noi. Extremely impressive display of firepower. Humongous explosions.

Now we were to move into positions on a piece of high ground that sat in the middle of the rice paddies with some 500 meters of clear, flat rice paddy to the north. Class for the boots on step 2, moving on rice paddy dikes and through ville areas. Stress on the mine and booby trap potential since that would be the most likely daylight threat to be encountered in that area. "Stay directly behind the man in front of you. Try to follow in his footsteps but do not get too close. Keep the gap at about 20 meters if the terrain allows it. Do not lose sight of that man. Do not, I say again, DO NOT touch or kick any thing you see laying on or near the trail."